This is what the Yvette Cooper memes tell us about British politics today

The most frightening examples were those that used violent language like ‘traitor’ and ‘sabotage’ because they normalise the kind of discourse that led to Jo Cox’s death

It’s nearly three years since Jo Cox was murdered – by a man who gave his name in court as “Death to traitors, freedom for Britain” – and people are still putting the word “traitor” on the faces of female MPs that they don’t like.

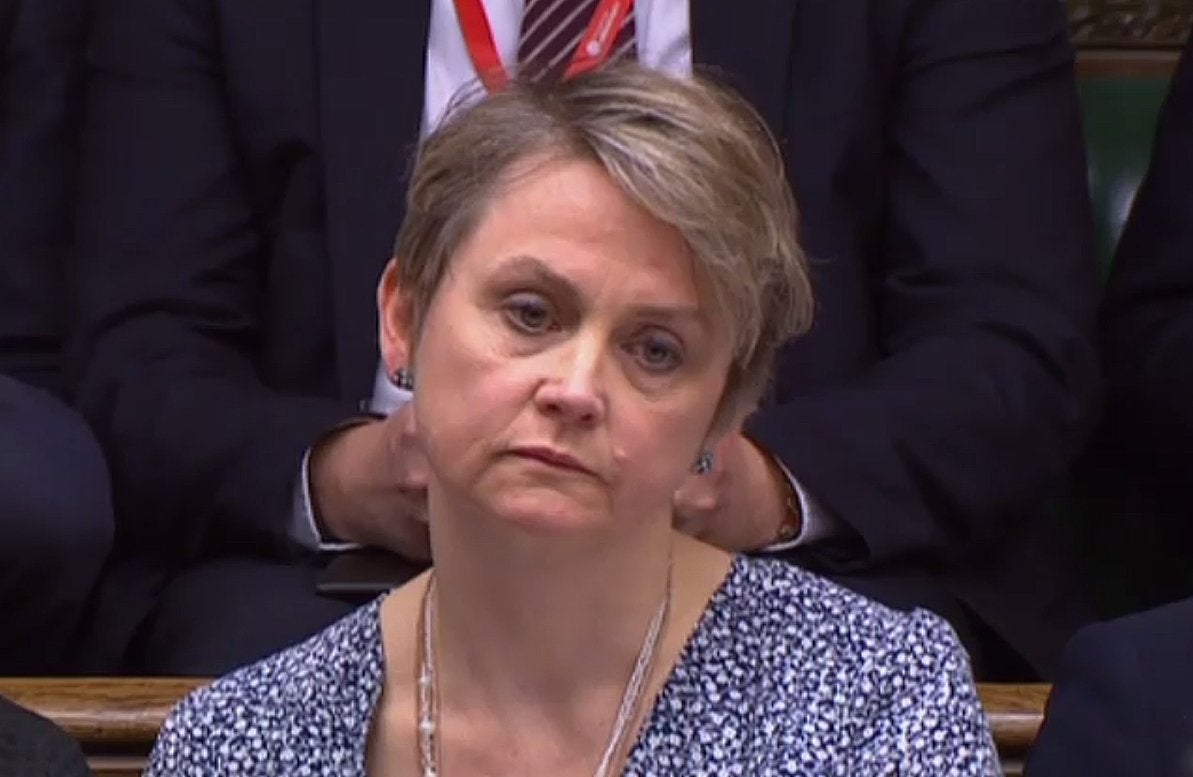

This week, it was the turn of Yvette Cooper. I have collected 88 different memes posted since last week that use her name, picture or both. Some have been posted or shared thousands of times across Twitter, Facebook and Gab, in a kind of Cooper anti-fandom. It’s not OK.

I was reading up on the various tabled amendments before the votes in parliament on Tuesday, to work out the likelihood of each passing. I looked up both Yvette Cooper and Nick Boles’ names on Twitter. I wasn’t really prepared for what I saw, and I’m someone who researches digital media and politics for a living.

Along with explainers and analysis, there were messages of support for the amendment and disagreement. There were also a lot of pictures, mostly memes combining images and text, often tweeted directly at Yvette. Right-wing journalists were sharing Cooper’s 2017 election leaflet, which became a meme in itself, especially when tweeted by Katie Hopkins, who dubbed Cooper and Boles “Brexit Traitors”. My feeds normally show me people pitting Cooper against Jeremy Corbyn as Labour leader, either positively or negatively – not this sort of stuff. I decided to dig deeper.

I collected anti-Cooper memes by running various searches on Twitter, Facebook and Gab, and looking at Leave and Remain accounts and pages, only collecting memes posted since the amendment was tabled. Some were obviously newly created, others date back to 2015 or earlier. As with Jo Cox, Cooper’s support for refugees was a key issue, and having campaigned for Remain in a constituency that overwhelmingly voted to Leave. Cooper’s election leaflet was mocked in the context of the amendment, because she said she would “not vote to block Brexit”. The amendment aimed to extend Article 50, not revoke it or cancel Brexit.

What characterised most of the memes, other than those graphics shared from the professional (and wealthy) Leave.EU and Change Britain campaigns, is that they were populist in both style and aesthetic. Bold messages, not very slick, sometimes showing the artefacts of over-pixellation and quick image editing on a phone, and pitting the people against the elite. Memes would either stick to stamping Cooper’s face with a single word like “TRAITOR” or “DEFEATED” or fill the space with lots of text, ranting about expenses claims (a story ten years ago, in 2009), refugees and “blocking Brexit”.

Particular memes got a lot of traction, unrelated to the slickness of their appearance, and particular photographs too – including one of Cooper looking sad after the amendment was defeated. Some memes were created from screenshots of news stories, Guido Fawkes blog graphics and print cartoons.

Unusually in the Brexit debate, Yvette Cooper attracts abusive messages and memes from all sides – left wing, right wing, Tory, Labour, Green, pro-Brexit and anti-Brexit. As a high-profile former cabinet member, her positions on other issues such as fracking, immigration and welfare are well known. Most of the memes, across the platforms, were shared predominantly by older people (over 45), many of whom had profiles using their real names and shared content suggesting that they were business owners and landlords. The abuse is not necessarily coming from those individuals dubbed “deprived” or “left behind”, even if they live in a Leave constituency. Some of the groups and accounts sharing the memes identified with the far right or anti-politics movements, others did not.

The most frightening examples were those that used violent language like “traitor” and “sabotage”, because they contribute to the normalising of that kind of discourse that led to Jo Cox’s death, and those who perhaps did not get hundreds of likes or shares or follows, but sent tweets daily to Yvette Cooper and her supporters, with homemade collages of memes or the same meme constantly. Even if Cooper does not look at her notifications, her office need to see her mentions and these images every day in order to carry out their work. As An Xiao Mina discusses in her recent book, Memes to Movements, memes “expand the range of acceptable discourse” and spread misinformation and disinformation. They also scare and upset people outside their target audience.

As for why Yvette Cooper? It seems like she scares people rather than someone to be ridiculed. The Corbyn-supporting left don’t like her or her policies, so she was easy target by Labour, Tories and Ukip, instead of lesser known MPs like Redcar’s Anna Turley, who actually supports a second referendum or People’s Vote – whereas Cooper does not. It has the strong feeling of an anti-fandom, with so many accounts and pages repeatedly sharing anti-Cooper visual content and enjoying ranting about her in comments and replies.

Concentrating on Cooper does not mean I ignore the massive amount of abuse aimed at other women in politics: Anna Soubry is characterised as drunk and a bad Conservative, Diane Abbott – the most targeted of all politicians – is the subject of sexualised memes and memes telling us she’s stupid (always sexist and racist), and Theresa May is usually just portrayed as weak. Yvette Cooper is seen as rich, traitorous, a liar, fraudulent, and best known for house-flipping in the expenses scandal and saying she would take in refugees and then not doing so. There are many anti-Corbyn memes from inside and outside Labour’s support base, but pro-Corbyn accounts post just as many Corbyn fan memes.

Most people are shocked to see these memes when I share my work on Twitter and Instagram, because in their part of the internet, they are never seen. We are living through a period of what I call the digital dissensus, following the post-war consensus and neoliberal consensus, where the old rules of politics don’t apply and media and the internet are fragmented. Meme creators, and many political figures, are only communicating with their fans, and accounts can have hundreds of thousands of followers without ever appearing on the news or most people’s social media feeds.

I don’t mean to scare you, but we should be scared. Not of the memes, but what they mean. Jo Cox has been forgotten, both as a symbol of where this language leads and as a real person. It seems ever more important to keep safe even those with whom you disagree – I don’t care if you don’t like Cooper’s politics, or anyone else’s – it’s not hyperbole to say that people get killed. Remain campaigners were calling Labour rebels traitors this week for voting against amendment, as well as Leave campaigners calling Tory rebels traitors for voting for it.

Communities remember – more in common is not just a slogan, it’s a reminder that the Brexit debate isn’t all Britain is, and Jo Cox is more than a pub quiz answer.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies