The Tories are on to a loser if the election comes down to horse trading

Ladbrokes are the only ones who give the Conservatives a hope of cobbling together a government

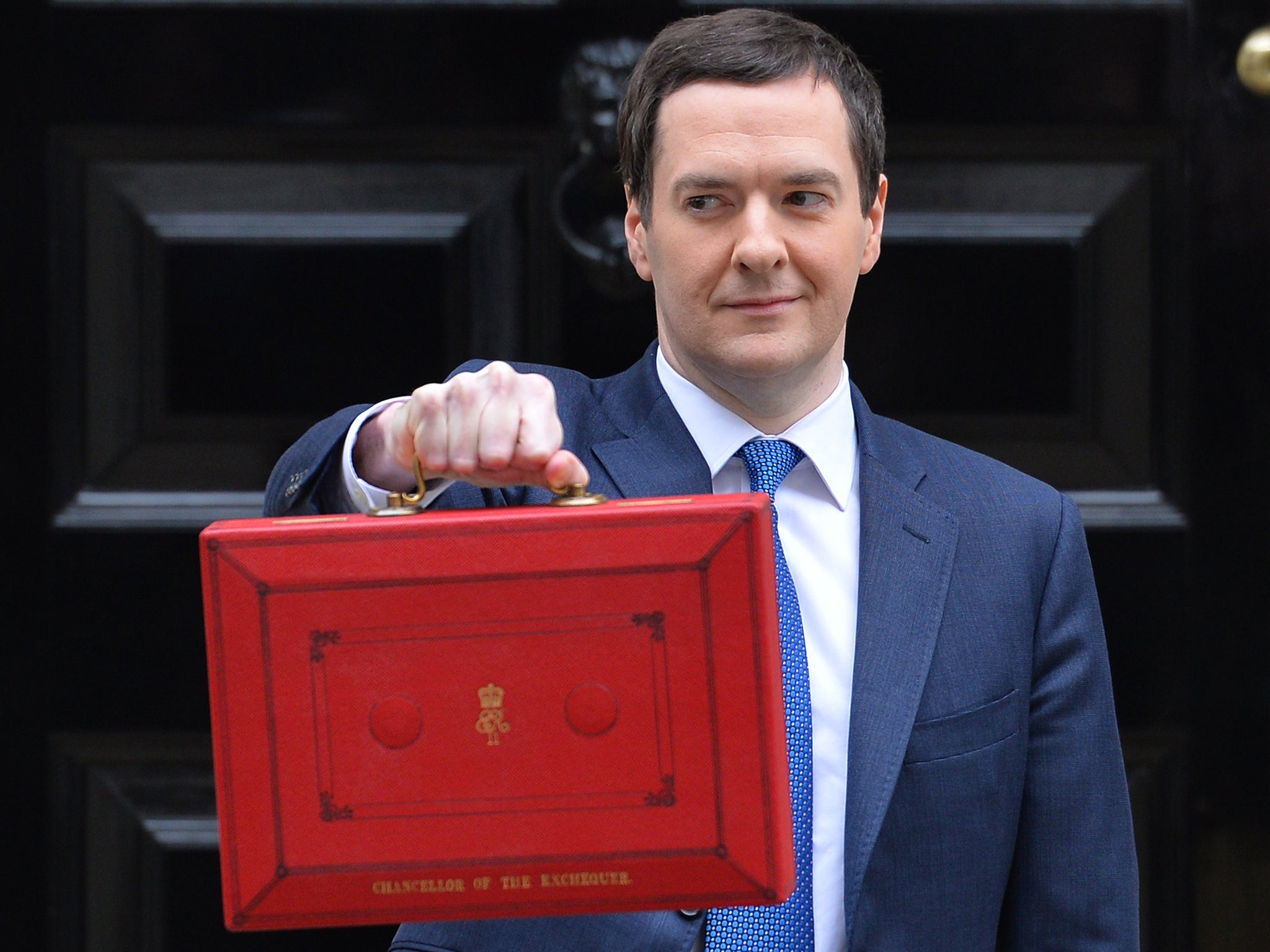

Deadlock in the opinion polls: the Budget didn’t budge it. George Osborne took no chances and declined to give voters a pre-election bribe. As a result, the Budget was well received – more people think the Chancellor is doing a good job than a bad one, according to YouGov’s post-Budget poll – but it did not move the market.

Specifically, it did not move the market in betting on the election result. It may be that the benefit of a prudent Budget will filter through to the Tories’ poll rating gradually. The public finances were in better shape last week than had been expected just three months ago, but Osborne chose not to bribe us with our own money. He said that, if he had done that, “we’d be spending money we didn’t really have”, which raised questions about whether money or credit is “real” or not. Instead of launching into a lesson on economic philosophy, however, he put all the “money we didn’t really have” into softening the edge of public spending cuts in the next parliament. That is, as I argued last week, what most people want, but whether they will be grateful I don’t know.

The outlook remains stubbornly unchanged, therefore, and if it stays like this there would be some uncomfortable consequences. To understand them we need to work backwards from the winning post. Conventionally, to win a majority in a House of Commons of 650 MPs, you need 326 of them. But because Sinn Fein’s five MPs don’t take their seats, 323 is a majority in practice – assuming that Michelle Gildernew, the Sinn Fein MP who won her seat by just four votes, holds it this time.

One of the implications of a properly hung parliament would be that London journalists would suddenly need to know a lot more about Northern Irish politics than they have known since 1998. It could be that the election will be decided by the Democratic Unionist Party. Last week it reached a pre-election deal with the rival Ulster Unionist Party, to stand aside in each other’s favour in four seats, but not in South Belfast. I think that means the DUP is likely to have nine seats in May, gaining one.

That also means that for David Cameron to remain as Prime Minister, the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats between them have to win 314 seats. Although the target might go down to 308 or 309 if Cameron were forced to do what would be to him a nightmare deal with Nigel Farage, who could be one of five or six Ukip MPs.

With six weeks to go, that target is on the edge of Cameron’s reach. Forecasts for the combined number of Tories plus Lib Dems range from 281 (Electoral Calculus, based on current opinion polls) to 310 (Ladbrokes, based on betting). Projections based on how opinion polls have moved before previous elections would suggest a total of just over 300. Only Ladbrokes gives Cameron the hope of cobbling together a government with Ukip’s support – and betting markets were less accurate than opinion polls last time.

There are no other sources of possible support for a Tory-led government. Northern Ireland’s SDLP, which is likely to continue to have three seats, almost always votes with Labour, and Sylvia Hermon, the independent Unionist, usually does too. In England, Cameron can rule out Respect’s George Galloway and Caroline Lucas, who I think will still be the only Green MP. As for Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon has said: “The SNP will not formally or informally prop up a Conservative government.”

The significance of this last, categorical statement, made on The Andrew Marr Show in January, has not yet fully sunk in. It means that, however many seats the SNP wins, it could prop up only a Labour government. Thus Ed Miliband would be prime minister even if the Tories were the largest party (the last time the second-largest party formed a government was also Labour, in 1924). At the moment, none of the forecasts gives Labour enough seats to reach a majority with the support of the Lib Dems alone.

If Cameron and Nick Clegg fall short of their target, Miliband would be in a stronger position than most people realise. The SNP would have no choice but to allow him to form a government. But that strength would evaporate instantly. Sturgeon could threaten to pull the rug out from under him at any time. She would have no fear of a second election: SNP activists would still be fizzing from their landslide and, though she cannot say so, a Tory government of the UK – even one led as it then would be by Boris Johnson – would suit her, because it would make a second referendum on independence more likely.

The prospect of a Miliband government propped up by the SNP is, however, one thing that could reinforce a strengthening of the Tory vote that I think is likely anyway over the next six weeks. Whether it gets Cameron and Clegg to their joint target of 314 seats is another matter.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies