‘This Is Going To Hurt’ is important viewing – but I won’t be watching

I’m glad the series has started a national conversation about the plight of maternity services and about the sometimes strained relationship between midwifery care and obstetric doctors

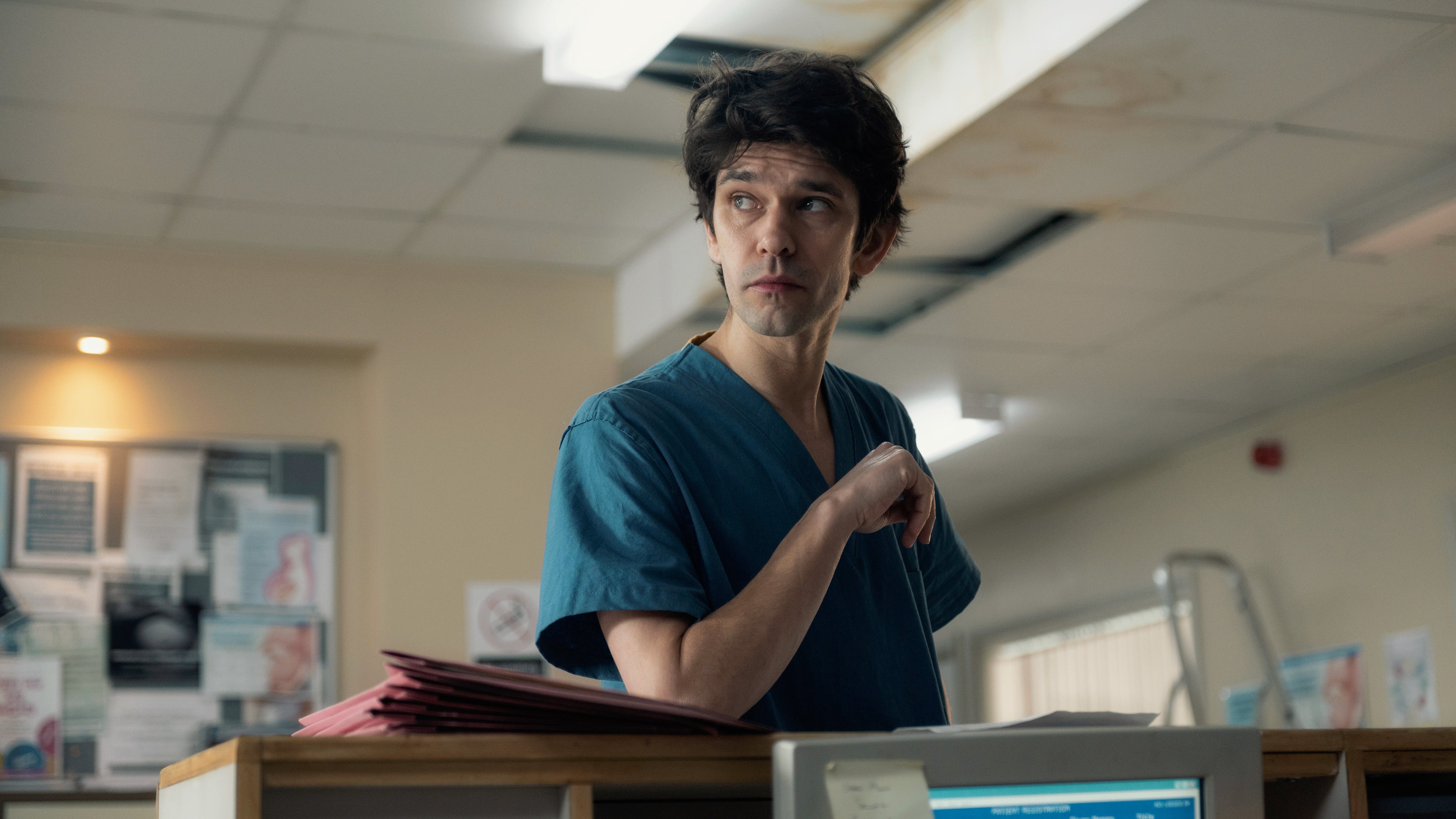

About two hours after I caught a snippet of Ben Whishaw playing the droll, acquiescent trainee obstetrician Dr Adam Kay in the trailer for the BBC adaptation of his book, This Is Going To Hurt, the flashbacks started.

First, of an anaesthetist taking his third attempt to site an epidural between the vertebrae of my spine, impatiently – and incredulously – asking me not to move as a wave of pain washed from my eyelids down to my toes.

Next, of the midwife who saw me six hours earlier and insisted I take opioids I didn’t want, who told me that I “wasn’t coping” with the normal progress of my labour. Then comes a memory of the semi-detached peace at hour 36, as my baby is delivered almost silently – I can’t feel anything – and placed, bloodily purple, onto my chest.

Finally, here comes the worst of it: the dissociation and panic as my newborn baby is taken from me, removed to neonatal intensive care, my husband accompanying her, while I am left alone in a room with a tepid cup of tea. I was pregnant, but now I’m not. Minutes ago the room was crowded with doctors, but now there is nobody with me at all. I can’t move my legs.

My first baby and I spent another week in hospital together (but mostly apart) after that, and every day of it was a physical and psychological trench battle. Sometimes, something unexpected will suddenly bring it all back. The particular sour scent of the hand soap provided inside any NHS or local authority building is a trigger I’ve learned to avoid. Thank you Covid, for reminding me to always carry antibacterial hand gel instead.

But almost five years on (and with a second, more positive birth behind me too) none of it bothers me quite so much anymore. It’s a part of my bodily history and it’s a defining moment in my relationship with my daughter, but the visual reminders that would jolt into my brain unannounced and rock me, a flicker of trauma that would last a second but could ruin an entire afternoon, have stopped.

Or they had, until I saw that trailer. That’s why I won’t be watching This Is Going To Hurt. It’s too raw, too painful and, even in those split seconds I saw, far too real. But the adaptation, which was released this month to mostly positive reviews, has served a purpose even for those of us who can’t bear to watch it – yet.

It has started a national conversation about the plight of maternity services, and about the sometimes strained relationship between midwifery care and the obstetric doctors who support their teams and their patients. It has highlighted in a visual, digestible way the pressure on maternity units and the risk that poses to pregnant women and their children.

There has also been a discussion about an alleged misogyny displayed in both the author’s original work and the TV script inspired by it. I certainly spotted moments of it in the trailer I saw, in which a women panting on a birth ball, in pain and lamenting the loss of her birth plan, was treated as a bit part in the drama. In that room, her journey to delivery should have been the main event. The sense of standing outside at a defining moment of your own life, and your child’s, was certainly relatable. Regrettable too.

If evidence of misogyny is found here, it wouldn’t necessarily reflect on the characters depicted but on the structure of services inside a monolithic medical institution. Medicine is an institution built on other institutions (the royal colleges, educational establishments and the like), all rooted in centuries of patriarchy. When birthing support was absorbed into it, along with improvements in maternal survival and neonatal health came those patriarchal norms.

Women’s pain and women’s physical experiences – including labour – are not treated equally within that system. Women going into these environments are vulnerable, and already at their most vulnerable.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

Other institutional biases are embedded too, such as racism and classicism. Women who experience other forms of discrimination are more likely to see this play out in the maternity ward. Black women, for example, are twice as likely to suffer a stillbirth in the UK as white women. Why? They are supposed to be receiving exactly the same care.

However, seeking to put women’s experiences at the centre of any story or policy around labour and childbirth shouldn’t crowd out discussion of the benefits of modern obstetrics – even when delivered in cash-starved hospitals creaking under the burden of working through two years of a pandemic.

In recent days, the NHS has dropped its requirement for maternity units to chase “natural birth” targets (that is, births achieved without medical intervention other than relief such as gas and air) and to benchmark caesarean section rates, after investigations into hospitals with high baby death rates.

This Is Going To Hurt helps to illuminate some of the backdrop to that story too. Birth can be chaotic, and for some women (although certainly not all), it can be dangerous. Interventions are often unplanned and decided upon in an emergency. And they are life-saving. This is not a world for the squeamish. Thank goodness obstetrics exists. Now please can we fund it, and all maternity services, properly so that fewer women face material danger while labouring and birthing.

So while I won’t be watching, I am glad this programme has been made. I am glad it is being talked about. I am glad it has provoked a debate, rather than a consensus, on how birth is managed and supported – and, sometimes, treated – in our NHS. If it has achieved that, it is worth the anxieties it set off in me for a few hours.

I won’t be returning to the postnatal ward again, but I still want a better experience for the women who come after me, for fewer of them to have to live with mental and physical trauma, and for more positive birth stories to be shared.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies