Sir George Martin was one of a rare, disappearing breed - gentlemen

Tributes to the music producer all agreed he was one, but what does it mean? And where are the rest?

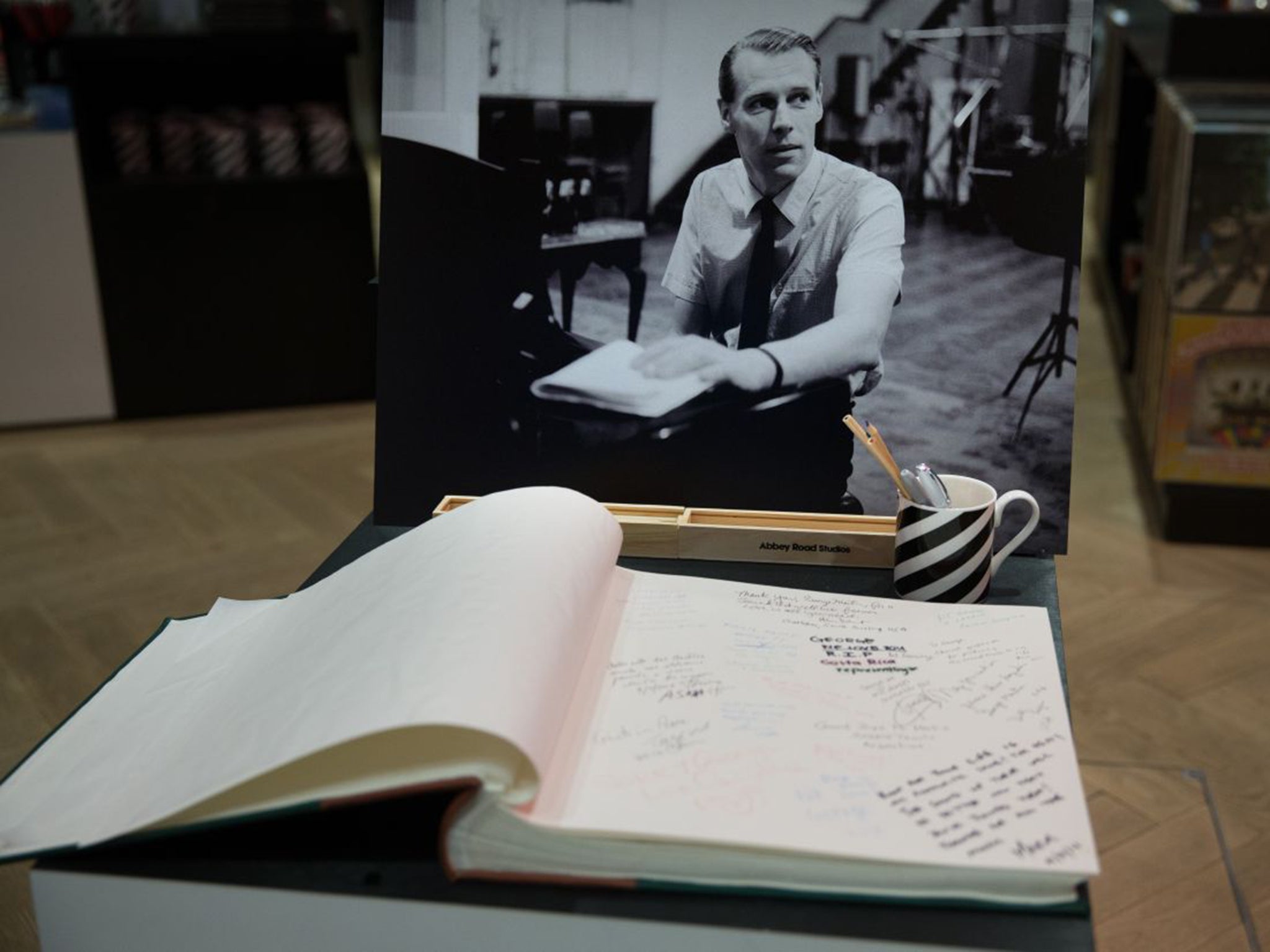

One of the most remarkable things about the obituary tributes to the music producer George Martin, who died last week at the age of 90, was the apparent evenness of the deceased’s temper. In fact Sir George, who has strong claims to be regarded as one of the 1960s’ most influential cultural figures, seems never to have had a bad word for anyone.

He may once have suggested that the covert, John Lennon-inspired tampering that went on with the tapes of the Beatles’ final album Let it Be merited the billing “Produced by George Martin. Over-produced by Phil Spector” but even in old age he was still feeling guilty about being “beastly” to George Harrison, whose talent he feared he had underestimated.

In a pattern demonstration of the old adage about reaping as you sow, this essential good nature was warmly commended by the memorialists. Quite as remarkable, though, was the language in which these send-offs were framed, and for every encomium to his genius as a studio technician and arranger there was a nod to what seemed to be an even more crucial attribute. Sir George, his fellow knight Paul McCartney assured us, was “a true gentleman”. Not only one of pop’s greatest producers, the Beatles’ biographer Philip Norman confirmed, but “unquestionably its greatest gentleman”. Even the Harrison family, beastliness forgotten, put out a statement that began “George Martin was a gentleman above all”.

And what, the amateur sociologist might wonder, does being a “gentleman” mean here in 2016? In the context of Martin’s relationship with the four Liverpudlians whose sound he honed, refined and embellished, the implication was that it had something to do with social class – “patrician” was another word that floated around the broadsheets on Thursday morning.

And yet, as Martin himself was always keen to point out, behind his slicked back hair and military bearing lurked the son of a carpenter-cum-streetcorner newspaper seller whose background was strikingly similar to John, Paul and George’s – if not the authentically working-class Ringo – and whose cut-glass accent was, like his job at Parlophone, acquired by means of a great deal of hard work.

Sir George, in the end, was less a product of the 1960s, when the “young meteors” of Jonathan Aitken’s genre-defining book of the same name really could come from nowhere, than a product of the much more conservative 1950s, when faces had to fit and aitches stay resolutely undropped. Clearly, he was a man who, confronting the exacting protocols of the Eden-era world of work, knew that to succeed it was, to an extent, necessary to reimagine yourself, and that surmounting, or circumventing, the social and professional barriers that lay across your path might sometimes require the jettisoning of a good deal of baggage picked up in early life.

But the question of his “gentlemanliness” returns us to a problem that has been puzzling social commentators for the best part of part of half a millennium. What is a gentleman? Can you become one, or is its essence breathed over your cradle? Is it a mark of rank or merely status? The original definition is not overly helpful as the “gentle” part, from the Latin gentilis, has nothing to do with mildness or suavity but here means “worthy or typical of a kind”, ie “genus”.

In the early modern era there was an idea that a “gentleman” owned land, and would offer military service to his liege lord, but in strict taxonomic terms it is hard to beat the formulation proposed by Simon Raven in his mock-sociological treatise The English Gentleman, which, coincidentally, was published only a year before the Fab Four first unloaded their van outside Abbey Road studios.

A gentleman, Raven tells us, is technically speaking “the younger son of a baronet or knight, the son of an esquire, a commissioned officer below the rank of ‘captain’ (or the naval equivalent) and, in general, any man of means or good profession who, while not an esquire, is yet not to be ranked with the yeomen”. It is that last clause which gives the game away, for what in these socially indeterminate times constitutes a “good profession”? A chartered accountant? A local government official? A teacher? A designer of computer games? Raven was writing in 1961, a time when social distinctions of this kind seemed in flux, but the suspicion that the term had lost any precise meaning was going strong at least a century before.

Anthony Trollope, for example, whose interest in gentlemanliness once inspired a book-length study by Shirley Letwin entitled The Gentleman in Trollope: Individuality and Moral Conduct (1982), includes a significant scene in his final Palliser novel, The Duke’s Children (1880), which takes in young Lady Mary’s attempts to persuade her father, the Duke of Omnium, that she ought to be allowed to marry a penniless Cornish squire named Frank Tregear. Parental opposition is based on the assumption that Frank “is not fit to be your husband”. To this Lady Mary retorts that her intended “is a gentleman, papa”, only for papa, grievously affronted, to declare that so is his private secretary, the curate of the parish and the local doctor, and that the word is “too vague to carry with it any meaning that ought to be serviceable to you in thinking of such a matter”.

That Lady Mary eventually gets her way didn’t detach this question from the Victorian equivalent of the online discussion forum: in some ways it only confirmed its imponderability. If, as it now seemed, a man’s status was defined by his profession, then who was to decide whether that profession was sufficiently high-powered to allow its representatives to be considered as gentlemen? The Victorian journalist was often uncomfortably aware that what he did for a living was not truly respectable, liable to be written off as “penny-a-lining”. That these attitudes softened over time is confirmed by a rather awful moment in Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London, written half a century later, in which our Old Etonian hero, queueing up to spend the night in a casual ward with a motley collection of vagrants, gives his trade as “journalist”. Immediately he is singled out by the official in charge, the Tramp Major, who demands of him: “Then you are a gentleman?”

Orwell replies that he supposes he is. “Well, that’s bloody bad luck, guv’nor”, the Tramp Major consoles him, “bloody bad luck that is”, thereby confirming another aspect of gentility’s mystique, which is that ordinary people seem rather to like identifying and responding to it, as in the “You’re a gent” acknowledgment of some minor courtesy, which persists to this day. At the same time Orwell’s gentlemanliness, to which all reports of him attest, was patently to do with his manner: the tweed suit which, however battered, had clearly been made by a very good tailor, that indefinable self-possession which invariably encouraged pub landlords to call him “sir” while addressing other people at the table by their Christian names.

All of which returns us to Sir George Martin who, though comparatively humbly born, was, once he came to prominence, indisputably a class act. How did he achieve this pre-eminence and acquire the almost moral resonance that came with it? So far as one can make out, through qualities such as tact, courtesy, self-effacement and subordination of his own interests to those of the artists for whom he laboured. As was more than once pointed out in his obituaries, a sharper operator would have seen to it that many of the Beatles’ early numbers were credited to Lennon, McCartney and Martin, with royalties to boot. And perhaps this lack of opportunism offers us another angle on the idea of the “gentleman” – how very few of them there are around these days.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies