Andreas Whittam Smith: Our legacy of 9/11 was a dictatorial and dysfunctional government

The reason why half the Cabinet didn’t know it was at war was that the Iraq engagement was being run exclusively by Downing Street

It was the day after 9/11.

Airspace was still closed to civil flights. British intelligence chiefs had flown by military aircraft to Washington to confer with their American counterparts. After their discussions had been concluded, they repaired to the British embassy and there talked late into the night. One of those present was Eliza Manningham-Buller, then deputy head of the British Security Service and responsible for its intelligence operations and subsequently its chief.

In her Reith Lecture this week, Baroness Manningham-Buller recalled that evening discussion. "We discussed the near certainty of a war in Afghanistan to destroy the al-Qa'ida bases there and drive out the terrorists and their sponsors, the Taliban. We all saw that as necessary." But what the group didn't foresee was "the decision of the United States, supported by the UK and others ... to invade Iraq and remove Saddam Hussein".

There were good reasons why they didn't see Iraq coming. Iraq was not top of the Foreign Office list of countries causing concern despite its stated desire to develop weapons of mass destruction. It ranked below Iran, North Korea and Libya. Dealing with Saddam Hussein through sanctions and other methods, as we were, was an effective alternative to military action. Moreover, the Government had investigated and rejected suggestions of links between Saddam Hussein and al-Qa'ida. Following the 9/11 attacks, the Foreign Office concluded there was nothing that looked like a relationship.

So it was against conventional wisdom that we joined the American invasion of Iraq. Just over 100,000 Iraqi citizens lost their lives and some 179 British troops were killed. It palpably increased the terrorist threat to the United Kingdom. On this occasion, at least, conventional wisdom was right. For Iraq turned out to be one of the greatest foreign policy mistakes of the past 70 years, ranking with the invasion of Suez in 1956.

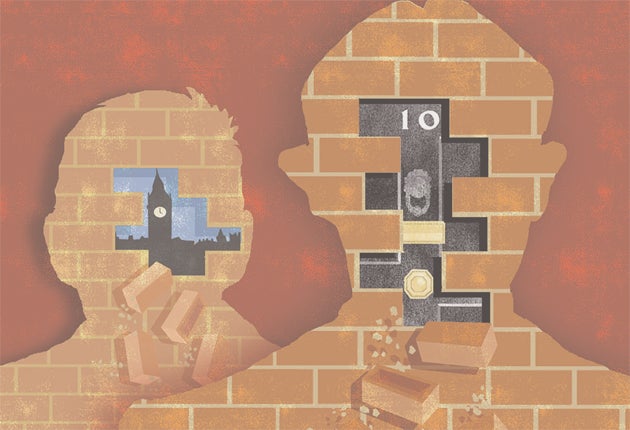

Ten years after 9/11, it is time to establish how it was that the Prime Minister, Tony Blair, was able to take us to war on his own say-so. The answer, which couldn't be foretold beforehand, was that Mr Blair would govern more like a president than a prime minister. Under British constitutional arrangements, there is nothing to stop a headstrong prime minister from doing that.

Talking to the Iraq Inquiry, Admiral Lord Boyce gave an insight into what was going on when he remarked that "half the Cabinet" did not think the country was even at war. "I suspect if I had asked half the Cabinet whether we were at war, they wouldn't know what I was talking about. So there was a lack of political cohesion at the very top." This is a revealing remark, because the reason why half the Cabinet didn't know it was at war was that the Iraq engagement was being run exclusively by Downing Street.

Never mind that Mr Blair lacked popular support. A couple of weeks before the war started, one million people marched through London to demonstrate their opposition. Compare this with 1914 when the European nations went to war. There were demonstrations of joyful patriotism in the belligerent countries. In 1939 the mood was much darker, but the British could see that they had to answer the call. In March 2003, however, even though it was but 18 months since the Twin Towers attack in New York had caused 3,000 deaths, there was only a sort of sullen resignation: "This is what we have been told must be done." Mr. Blair had come to like playing the lonely hero.

Never mind that the decision was of "questionable legitimacy", as Sir Jeremy Greenstock, the British ambassador to the United Nations, put it. Swat away the objections of Jack Straw's chief legal adviser at the Foreign Office, Sir Michael Wood, who considered that the use of force against Iraq in March 2003 "was contrary to international law". When Lord Goldsmith, the Attorney General, told the Foreign Secretary that he felt he might need to tell ministers the arguments were "finely balanced", Mr Straw advised him to be aware of "the problem of leaks from that Cabinet" and suggested he instead distributed a "basic standard text" of his position and then "made a few comments". Mr Straw nevertheless has rejected suggestions that cabinet ministers were not fully aware of the finely balanced arguments.

Never mind that Britain didn't have sufficient military resources to conduct simultaneous wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. When Lieutenant General Sir Richard Shirreff went to visit Basra in 2006, he found that 200 troops were attempting to control a city of 1.3 million people, with militias "filling the gap". The British Army was effectively providing "no security at all", he said. Admiral Lord Boyce drew the bigger picture for the Chilcot inquiry. While Tony Blair has repeatedly said that he never rejected requests for equipment from the military in Iraq, Lord Boyce claimed that when the requests landed on the desk of the then Chancellor, Gordon Brown, "there was a brick wall".

More significant still is the evidence given to the inquiry given by Lord Turnbull, who was Cabinet Secretary during the early stages of the war. But, before I quote from him at some length, I want to introduce a second factor that could not easily have been foreseen by Baroness Manningham-Buller and her colleagues when they were talking in Washington 10 years ago. At the same time that the British system of government was becoming presidential, it was also becoming dysfunctional. What Lord Turnbull said was this: "They (cabinet ministers) had had many discussions but no papers." I pause here. No papers? How can you possibly have a serious business discussion without papers? "More importantly," Lord Turnbull went on, "none of those really key papers, like the options paper in March 02, the military options paper of July, none of those were presented to Cabinet. That is why I don't accept the former Prime Minister's claim they [the Cabinet] knew the score."

You can see what is going on here. If you starve your colleagues of information, they cannot mount effective criticisms of what you are proposing to do. More from Lord Turnbull: "The Prime Minister's favourite way of working was to get a group of people who shared the same endeavour and to move at pace and not spend a lot of time arguing the toss... On the one hand, you move effectively ahead but when it comes to the point of engagement and responsibility, you are then asking people to take responsibility for something they have had very little to do with." Actually it would be better to call that a bastard form of presidential government – all the disadvantages and none of the benefits. Gordon Brown carried on in the same way. But just the other day, Alistair Darling said of Mr Brown's time as prime minister "there was a permanent air of chaos and crisis".

Now Mr Blair and Mr Brown, tested and found wanting, have left the stage for ever. And with them has gone creeping presidentialism that in turn was the cause of dysfunction. We've had a President Blair and a President Brown. But coalition government cannot allow such a role. So we have gone back to having a mere prime minister. We have returned to normal.

a.whittamsmith@independent.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies