Europeans are out of love with EU institutions, but still committed to the union

To keep the euro steady, it's vital that the ECB and other institutions regain public trust

Any football fan will be familiar with the tendency of supporters to heap opprobrium on a failing manager and yet remain staunchly committed to the team itself (there’s nothing worse than a fair weather fan, after all). Luckily for fans of European integration, the same seems to be true for the ‘European Project’.

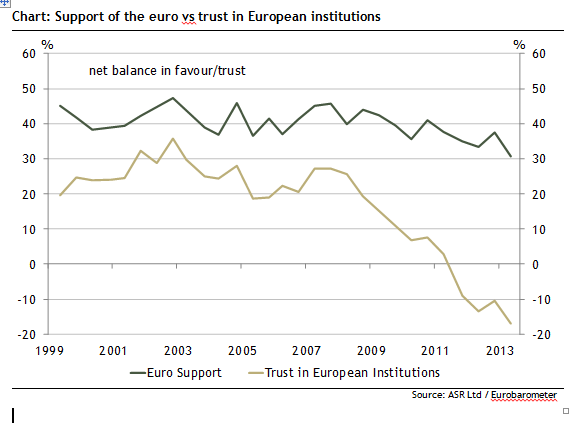

Eurozone citizens’ disdain for the custodians of Europe – the Commission, the ECB, the Parliament, and others – has never been deeper. The results from the latest Eurobarometer (a twice yearly survey of around 30,000 European citizens) tell a sorry tale of the fall in confidence in European institutions since the crisis began.

But Europeans are no fair weather fans of the EU or the euro. Despite the prolonged recessions most have suffered thanks to the euro crisis, 62 per cent of those living in the eurozone remain supportive of the single currency. In the EU as a whole, 56 per cent disagree with the notion that their country could better face the future outside the EU (33 per cent agree).

The story that emerges from the data is one of a citizenry which remains, despite the current hardships, committed to an integrated Europe but which has grown profoundly disillusioned with the institutions that run it.

This could be a problem. These institutions may need to be empowered like never before if further European integration is to be achieved within a stable framework. Such integration, most analysts agree, will be instrumental to putting the euro onto a sustainable long-term footing. Without it, the positive moves which we saw in the European economy this week will serve simply to delay the point at which the eurozone’s innate imbalances bring on the next crisis.

This integration will become more difficult to achieve the more the credibility of the institutions charged with presiding over it erodes. As the European Commission and ECB have failed to take steps to curb joblessness in Europe, whilst at the same time helping to enforce austerity throughout the Periphery, they have looked more and more like part of Europe’s problem rather than the solution.

Angela Merkel’s statement on Wednesday that ’more Europe’ could mean “coordinating national political actions more intensively” and did not necessarily mean only “transferring competences from national states to Europe” was an important one. Merkel’s apparent cooling towards the further centralisation of powers in Brussels dovetails with Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte’s statement in June that “the time for ‘ever closer union’… is at an end”. There is an aversion across the Nordic countries to integration that would come at the explicit expense of national sovereignty. There is also a clear preference across Europe to avoid treaty change that would launch a cascade of referendums that could prove difficult to win (memories of the failed EU constitution remain raw, particularly in Paris). To achieve this, the EU’s institutions may have to be sidelined.

It’s worth noting that a deep groundswell of support seems to remains for the (admittedly imprecise) concept of “building Europe”. Citizens asked at what speed they would prefer that process to take place on a scale of one to seven plumped on average for a respectable five. Perception of the ‘actual’ speed was a mere 3.2, implying that most want more integration than they think they’re currently getting! What form that integration is the crucial question. Merkel’s shift of focus away from Europe’s institutions looks to be an astute one. What that leaves in their place is unclear.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies