Tom Sutcliffe: Tales of mystery and imagination

The week in culture

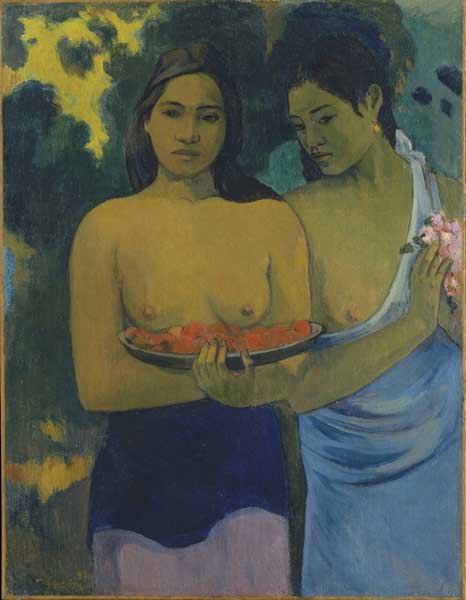

One of the more engaging objects in Tate Modern's current Gauguin exhibition isn't a painting at all, but a house-front; four carved panels which Gauguin created to decorate his home in the Marquesas. This is, I should stress, a wayward judgement and a faintly perverse one – which stems, at least in part, from the fact that I found myself oddly disengaged by the paintings. It was one of those exhibitions, I found, where I could see the merits of the works but couldn't really feel them. So, in room after room, I admired his mark-making and his use of colour and the boldness of his simplifications, but then found myself moving on unmoved.

But these four great planks of wood – carved in a low bas-relief with Polynesian maidens and ornamental figures – stopped me in my tracks. And it wasn't the sculpture that did it so much as the writing. Above the lintel Gauguin had carved a name – "Maison du Jouir" ("house of pleasure") – a gesture the curators suggest was a deliberate affront to the missionaries who lived nearby. Since the French words could also potentially be translated as "house of orgasm", Gauguin was cocking a snook – or some more relevant part of his anatomy – at pious seemliness. That made for a good story, I thought, the neighbour from hell pitching up to undermine all your good efforts. On the right-hand side of the door Gauguin had elaborated on this idea. "Soyez Amoureuses et Vous Serez Heureuses" ("be loving and you will be happy"), he'd etched, above two female heads looking a little come-hither at the viewer. This I wasn't too sure about, since it carried more than smack of self-justification – the libertine's pretence that his pleasure is a kind of philosophy.

But on the other side was the real point of this object – the instruction "Soyez Mystérieuses" ("be mysterious"), a motto that also features in other Gauguin works, and was obviously central to his self-image. This, too, is open to a cynical interpretation – if you take it as a kind of marketing guide for the aspirational Bohemian artiste maudit. Gauguin, as you learn here, usually preferred his Tahitian paintings to retain their Polynesian titles when he shipped them to Paris for sale; that way they retained their marketable enigma as exotic objects. And that kind of calculated mystification isn't necessarily a good thing in art, since it's so easy to employ it in cases where it masks an essential vacancy. What lies behind the veil? Well, quite possibly, another veil, just in case the first one gets dislodged.

I don't think Gauguin is open to that charge, in fact. If anything his works strive a little too hard to incorporate mythic meaning – drawing both on the mythological structures of France and the South Seas (he has crucifixions and depositions alongside his Polynesian legends). But you can see how easily ersatz mystery might provide a substitute for genuine content.

In an uncynical reading, though, "Soyez Mystérieuses" is one of the great artistic credos, particularly when applied to narrative or representational work. It's hardly an injunction of which you need reminding if you're working as a conceptual or installation artist, when mystery is your raw material. But when the painting (or play, or film) can be said to be "about" something, and when the audience's incorrigible instinct is to translate that "about" line for line, it's often what divides great work from the merely workmanlike. Howard Hawks understood this just as well as Gauguin, or – in a different way – Shakespeare. Being mysterious in this reading isn't effortful opacity, or obscurity masquerading as depth. It's simply a matter of content that is extraneous to the work's obvious intentions, that in some odd way lies at an angle to it. You can't say what it's "about", because being "about" something is not why it's there. It may even be a distraction from the artist's main intentions, a detail that can't account for itself in any one-to-one tally of components and function, but which can't be removed without making the work die a little. So, I wasn't overwhelmed by Gauguin's paintings – but he did a great bumper sticker.

A poem that proves to be a bit of a mouthful

No question that the BBC's decision to dramatise Christopher Reid's poem "The Song of Lunch" is admirable. It flies in the teeth of demographic caution and trusts that an audience will be patient with a drama that obeys few of the rules of TV narrative. Though it unfolds in something very close to real time it moves slowly, and it doesn't offer the kind of neat resolutions that TV audiences have grown accustomed to. And as a two-hander it allows for real attention to the performances of Alan Rickman and Emma Thompson. So it is a good thing for TV. Whether it's a good thing for Christopher Reid's poem I'm less sure. The thing is that real images are generally poorer than poetic ones, and since the verse has essentially been used as a shooting-script there are a lot of occasions when description and things overlap. "The lift yawns emptily", writes Reid at one point. And we see a lift yawning emptily. Except, of course, that what we see is just a lift and the banal familiarity of the sight tends to block out the unfixable amalgam of feeling and function that Reid achieved. The picture takes a two-tone line and flattens it into a kind of literalism. Where it still works, significantly, is where no literal depiction of the words would be conceivable. "For a moment he halts, mouth full of pause/ Which he can either spit out or swallow", writes Reid, about a moment of mental hesitation. You can't show that on a screen, so it adds to the picture rather than simply subtitling it, as does Reid's fine description of his character's retreat to the restaurant toilet, where he inhales "the jabbing kidney reek that proclaims all men brothers". Again, impossible to film and impossible to reduce to a mere stage direction.

Vampires are not the only fright

It's intriguing that Jeanette Winterson has accepted a commission to write a horror novel for Hammer, who are extending their franchise into the book trade. She's always been a writer with a passion for the fantastical, and she's certainly capable of producing something that won't make your skin crawl, at least when it comes to literary style. If she wants to shoot for greatness, though, one thing is very important. She must invent her own monster. Hammer presumably intended to tap into the current vampire boom, as exemplified by True Blood and the Twilight books. But it would be very boring indeed if we got another of those everlasting teenagers, sleeping in late, moping about the place feeling sorry for themselves and occasionally biting chunks out of innocent bystanders. As a horror trope they're surely getting decidedly anaemic these days. Difficult as it would be to pull off, Winterson should aim to find an as yet untouched nerve in the human psyche. She has distinguished predecessors in the form of Mary Shelley and Robert Louis Stevenson, both of whom came up with fresh dreads that have been re-imagined again and again. I'm sure Winterson will do something scary whatever she writes. But if it's to be more than a curiosity she needs to start an entirely new blood-line.

t.sutcliffe@independent.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies