Tom Sutcliffe: Music is the only true Hendrix experience

The week in culture

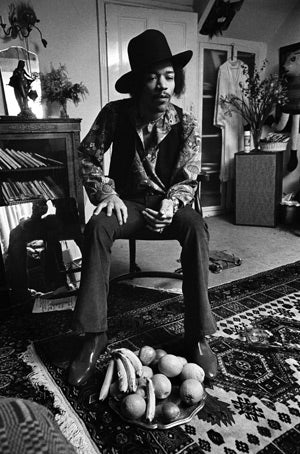

I visited Jimi Hendrix's flat the other day, but unfortunately he wasn't in. Given that he died 40 years ago – and that his flat is currently occupied by the administrative offices of the Handel House Museum, that wasn't entirely surprising. But the hope that he might be there had travelled with me – as it will no doubt travel with the Hendrix fans who have already snapped up all the available tickets for a brief period of public access to the same space, part of the museum's current Hendrix in Britain show. That's what visiting the homes of dead artists is about, after all. The desire, even the expectation in some cases, that we will find them at home, that this space may fix and define our hero or heroine in a way that their work has not. As I say, it didn't exactly happen for me – perhaps because I saw Hendrix's tiny upstairs flat before it had been cleared out for viewing and the museum's back-office workers were still all crowded in there too, doing their paperwork and making it a bit trickier to summon the presence of the departed. But it was probably also because I've never been very good at channelling the artistic dead, anxiously aware that while other people are claiming to get a powerful sense of character, I'm quite often standing there thinking, "Well, it's an empty room".

Empty rooms aren't without their messages, of course, and in quite a lot of museums and artistic shrines they aren't empty anyway – frequently stuffed with the bric-a-brac and leavings of the dead artist, which is often arranged in as close an approximation to naturalism as curatorial nervousness will allow. That can work to help the less sensitive amongst us generate the "just left the room" feeling which everyone is striving for. But even here I find myself a little wary of the myth of presence. It seems to have more to do with our desire for intimate contact than with contact itself. Hendrix's flat, for instance, tells you little more than how little that space is – and in thinking that (thinking, "Gosh, Hendrix and Clapton once squeezed up these steps"), we're really only measuring their imaginary stature in our heads (there were giants in those days) against the human reality. It is, I suppose, why people are always interested in the lavatory arrangements in these places (even if they don't dare ask). We like to reclaim artistic greats for the human community. So it's oddly comforting to learn that Hendrix shopped for his carpets and curtains at John Lewis – just a few blocks away from the Brook Street flat – though it tells us absolutely nothing about his genius, any more than possessing John Lennon's former lavatory will give you access to his talent.

And quite often what you find yourself doing in such spaces is not imagining what the artist might have felt or seen, but what it might have felt like if you were the artist. You visit Dove Cottage, and peer out of one of its windows and think (provided you've chosen the right window), "Wordsworth would have seen almost exactly this view". If I had been Wordsworth – the subterranean feeling runs – this is what it might have felt like to be me. Which is, of course, absurd – and distracts us from the fact that the very best clues to an artist's life and perceptions are the works they leave behind. There are very engaging things in the Hendrix in Britain exhibition – things which come very close to generating that sense of being in the company of genius. But the things that do it most effectively are the personal stereos dotted around the room which allow you to listen to his music (and which technology will now allow you to access at virtually every spot on the planet). He happened, by chance, to pass through these rooms, and if they had been in another street or another city it wouldn't have greatly mattered. But the music is where he still lives.

Just press play for a taste of the latest theatre

The theatrical trailer has been around for some time now, with both the National Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Company offering stylish little video teasers for their productions on their websites. They tend to go in for deep chiaroscuro in these things (so much cheaper than a set) and an enigmatic style, rather like a moody men's fragrance ad. And in a startling number of cases the visual rhetoric also owes something to cinematic horror, with shock-cuts and that modish staticky stutter on the graphics – like a shorting electric connection.

But the trailers for the West End revival of Ira Levin's Deathtrap – embedded in a website near you and available on YouTube if you haven't yet stumbled across it – are a definite step up in ambition. There's a clever animated version, in which murderous figures are created by a chattering typewriter, and a live-action one, filmed on real locations with all the principle actors. Most of the YouTube hits appear to be the result of teenage girls pursuing a hopeless passion for Jonathan Groff, but I presume the odd casual punter must have come across the trailer too. And the thinking seems to be that potential punters can be lured to the box office if they think that what they're going to see is sort of like a movie. I hope it works – and that novice theatre-goers aren't too disappointed when they find it's just a lot of actors in a big room.

All quiet on the viewing front

Not everyone likes the "quietly comic". This sometimes being taken as a euphemism for "laughless". I like these type of comedies a lot though, and we seem to be passing through something of a renaissance of the form just recently. Jo Brand's Getting On, set on a geriatric ward, and James Wood's Rev, centred on an inner-city vicar, have recently finished their runs, but Roger and Val Have Just Got In and Simon Amstell's Grandma's House are still going out. All of them share a lack of terror about awkward silences, a sometimes brilliant obliqueness in the writing style and – every now and then – a sense of real melancholy. And they are all funny – to my mind at least – in the most serious way, because they acknowledge, in among the comedy, that not everything is a laughing matter. And yet I'm not sure you'd really know from the press coverage or the audience figures that there are pearls strewn all around us. I think it's a classic case of superfluity making us complacent about what we've got. It's not so much that there too many good comedies (even with this blip there aren't enough). It's just that there are far too many TV channels and programmes full stop – so that even good programmes are only likely to find a small following or feel like an entirely private passion.

t.sutcliffe@independent.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies