Sign up to Miguel Delaney’s Reading the Game newsletter sent straight to your inbox for free Sign up to Miguel’s Delaney’s free weekly newsletter

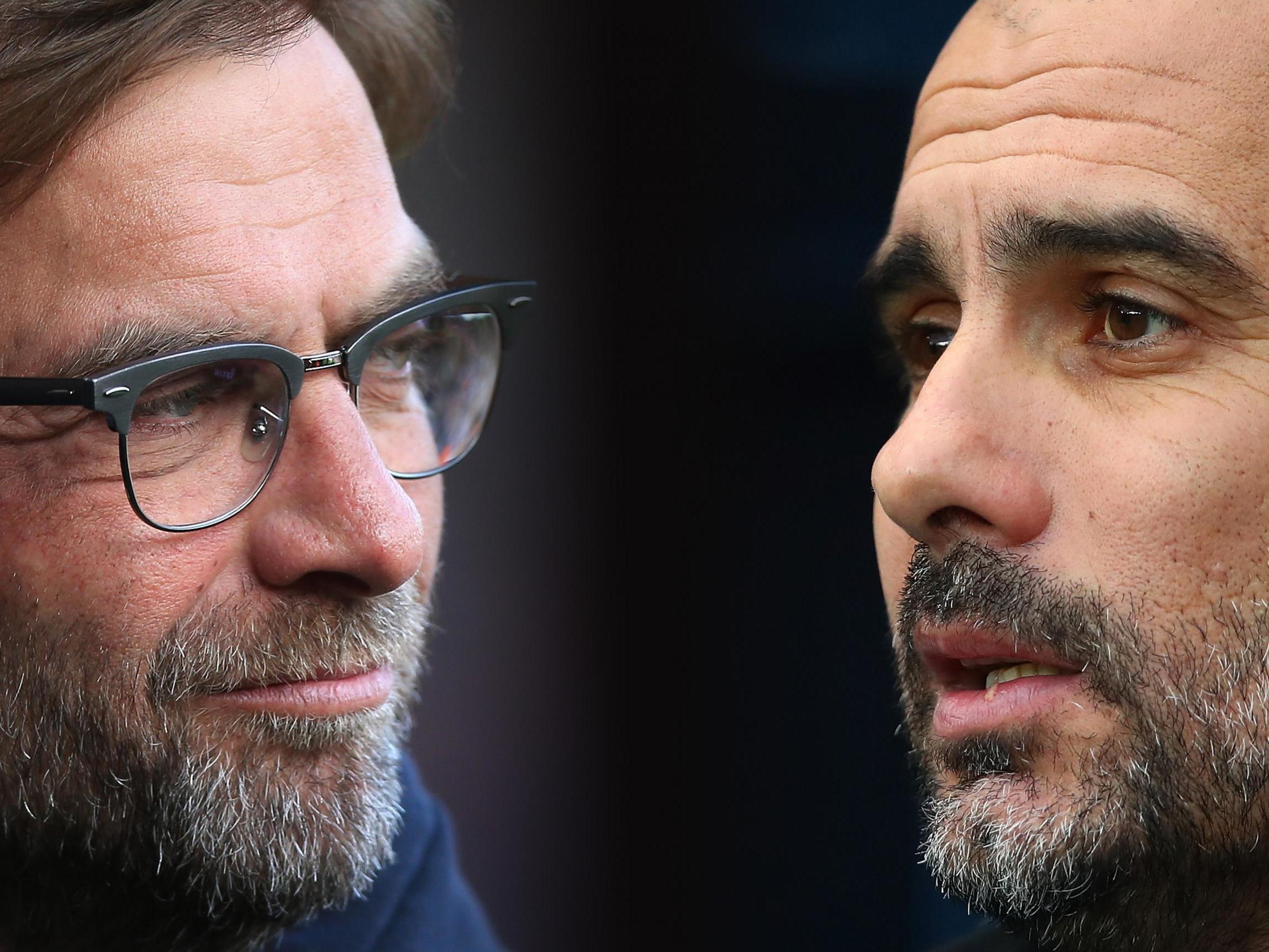

You wouldn’t quite call it an epiphany from Jurgen Klopp , but it was a distinctive evolution in his thinking. At an early point in his time at Liverpool , which appropriately happened to be just after the middle of the decade, the German realised his football would have to become even more nuanced than the raucous approach that was so successful at Borussia Dortmund . Klopp knew he needed more control.

Across the northwest of England, although largely influenced by his time at Bayern Munich, Pep Guardiola was soon coming to the opposition conclusion. He realised his control-based game needed to be complemented by more directness, more chaotic electricity.

The combined effect of this is that it means both sides now play hybrid approaches, and that their meetings represent the peak of the game. City-Liverpool has overtaken Barcelona-Real Madrid as the highest-quality fixture in world football, becoming the match where the sport’s latest tactical innovations are displayed. And that at an utterly frenetic pace that is often bewildering.

That is apt because this has been the decade where the tactical development of the sport has evolved at a faster rate than ever before too. It is exponential, with each new idea very quickly being absorbed into the previous to pick up more and more speed.

It has been the great mark of football’s last decade that the game has opened up so much. It genuinely looks so different to what it was in 2010, the late 20th century individualism having given way to a co-ordinated collectivism that would have seemed otherworldly then.

Show all 101 1 /101100-1: Century countdown 100-1: Century countdown The Century countdown This week, The Independent is counting down the 100 greatest players of the 21st century. We will be revealing 20 players per day, today revealing the players who placed 100-21.

100-1: Century countdown 100. Yaya Toure A brilliant midfielder who had everything: skill, tenacity, power, goals, energy. His defensive capabilities brought him to the fore at Barcelona before his attacking prowess made him such a weapon for Manchester City. He won two Ligas, three Premier Leagues, one Champions League, captained Ivory Coast to the Africa Cup of Nations and was African Player of the Year four times. LO

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 99. Harry Kane His raw statistics are simply phenomenal. 130 Premier League goals for Tottenham Hotspur, in just 186 appearances. 27 in 42 for England. Twice a Premier League Golden Boot winner. A World Cup Golden Boot winner. Tottenham’s talisman. England’s captain. And still just 26 years old. In 10 years’ time, expect to see Kane in the top 20 of a similar list. LB

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 98. Daniele De Rossi A ferociously competitive and combative midfield hard man, who made over 600 appearances for his beloved Roma and over 100 for his national team. A complete midfielder, who could in one passage of play win the ball, race forward and either release a team-mate with a pinpoint pass or score himself. And do not be fooled by his combustible reputation: in 2016, he placed his treasured World Cup winner's medal in the coffin of Pietro Lombardi, Italy’s kit man at the tournament. LB

AFP/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 97. Bastian Schweinsteiger The meticulous German orchestrated Bayern Munich's midfield to eight Bundesliga titles and a Champions League, making over 500 appearances for the club. He was also one of the leaders in Germany's 2014 World Cup-winning campaign and carried an aura in the centre of the pitch few players can claim to have replicated. TK

Bongarts/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 96. Vincent Kompany It’s difficult to define his importance to both Manchester City and Belgium but it’s safe to say he was one of the most important players of a generation. There may well be a handful of technically better centre-backs but his intangibles were vital to the culture at club and country where there was not a legacy of winning previously. JR

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 95. Karim Benzema One of the few strikers on this list who can truly claim to be the complete forward, able to play wide or central, deep linking play or on the shoulder of the last defender, with the ability to sniff out scrappy goals and score beauties too. His medal haul speaks for itself, and he is approaching 300 career goals. But for his strained relationship with the French national team, he would have scored even more. LO

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 94. Sol Campbell The heartbeat of Arsenal's defence in the Invincibles season, a double-winner in 2002 and a mainstay of the England team for almost a decade, Campbell is one of the defining defensive figures of the Premier League era. TK

AFP/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 93. Pepe One of the great villains of the game but a nasty, hard centre-back that would be very high on any great striker’s list of defenders he least wanted to play against. While his grit and determination stand out, nobody lasts a decade at the Bernabeu without possessing exceptional quality, with three La Liga titles (which has eluded the club since his departure) and as many Champions Leagues, Zinedine Zidane would be wise to acquire a similar player now. JR

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 92. Edwin van der Sar The four-time Premier League winner made over 300 appearances in England and made an enduring habit of thriving under pressure, winning the man-of-the-match award in Manchester United's Champions League final victory in 2008. TK

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 91. Arturo Vidal Only the finest players in the world enjoy long and fruitful stints at clubs such as Juventus, Bayern Munich and Barcelona. Il Guerriero has matured into a splendid holding midfielder, aggressive and dominant in the middle of the pitch but equally as effective arriving late into the box to complete attacks. A hero in his native Chile, for his role in the 2015 Copa América victory. LB

Bongarts/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 90. Angel di Maria A key player in the glorious Real Madrid side that won La Liga in 2011/12 and the Champions League two seasons later. Widely considered a flop when he left Manchester United after only one miserable season, but the Argentine completely reinvented himself at Paris Saint-Germain, the starring attraction in one of the most expensive squads ever assembled, containing the likes of Neymar, Kylian Mbappé and Edinson Cavani. LB

AFP/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 89. Diego Forlan A figure of fun in his early Premier League days at Manchester United, Forlan went on to have the last laugh with a stellar career both internationally with Uruguay and in Spain, where he racked up goals for Villarreal and Atletico Madrid, twice winning the European Golden Shoe. LO

AFP/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 88. Radamel Falcao In his pomp Falcao was probably the best striker on the planet. In a prolific four-year spell playing for Porto and Atletico Madrid he scored 142 goals in 178 games, and had injuries not hindered his career there is little doubt that Colombia's record scorer would be much higher up this list. LO

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 87. Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang Has excelled in a thoroughly mediocre Arsenal side for two seasons now, scoring at a rate better than a goal every other game in a side that has struggled since the departure of Arsène Wenger. But it is primarily for his achievements at Borussia Dortmund that he makes this list. He scored close to 150 Bundesliga goals for that wonderfully attacking team – including 31 in one season – winning the Bundesliga Player of the Year and Top Goalscorer awards. There have been few strikers as rapid or as decisive in front of goal in the last two decades. LB

Bongarts/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 86. Robin Van Persie One of the best left foots in Premier League history graced two of its most revered clubs, becoming a star at both Arsenal and Manchester United. The Dutchman had a penchant for the spectacular but suffered with injuries, and it is a sign of what could have been that in the two Premier League seasons he played more than 30 games, he won the Golden Boot in both. LO

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 85. Carlos Tevez A real pest of a striker who thrived in the hottest atmospheres and regularly overcame adversity. He scored plenty too, 116 league goals in eight seasons with United, City and Juventus (who probably all enjoyed prime Tevez), but it was the way he would trigger his teammates by forcing the first mistake or sparking counterattacks that really made him such an invaluable player. JR

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 84. Gaizka Mendieta The midfield maestro could control games and decide them too, and was at the heart of the brilliant Valencia team which reached back-to-back Champions League finals in 2000 and 2001. He became one of the most expensive players of all time when he switched to Lazio, but he would never again reach the heights that made him a legend at the Mestalla. LO

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 83. Virgil van Dijk The defensive talisman cast a spell of leadership over Liverpool's 2019 Champions League-winning side and went the entire campaign without being dribbled past. Few defenders have carried such an overarching influence on any side in recent memory. TK

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 82. Hernan Crespo One of the finest finishers of a generation but perhaps his best quality was his movement; particularly in the box, where nobody was more lethal at finding a yard of space and punishing opponents. Strong and an aerial threat, he was perhaps unfortunate to follow Gabriel Batistuta with Argentina, otherwise he would have been appreciated even more. Certainly as talented as Sergio Aguero and with perhaps more composure in the biggest occasions - an underrated player. JR

AFP/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 81. Rio Ferdinand A gem of a centre-back, who was perhaps ahead of his time, right now he would be even more valuable due to his versatility to thrive under any manager, no matter the philosophy or style of play. Became a real winner and leader at United and formed one of the greatest partnerships in international football history alongside John Terry with England - who should have obviously achieved much more with such an outstanding foundation to their team. JR

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 80. Toni Kroos A metronome in the middle, one of the finer passers in the world of football and the beating heart of a number of very successful sides, not least the World Cup winning Germany side of 2014. Four Champions League crowns as a key cog for Bayern Munich and Real Madrid underline his quality, but if you are to criticise it is that there have always seemed to be others doing more around him. HLC

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 79. Juan Roman Riquelme A traditional No 10 who was unhelpfully branded the ‘new Maradona’ when he began setting the Primeira Division alight with Boca Juniors. His £10m move to Barcelona in 2002 did not exactly go as planned – with another talented Argentine poised to write himself into club folklore instead – but Riquelme made a success of himself in Spain with Villarreal under Manuel Pellegrini. A true artist who shone in an advanced playmaker role, before dropping deeper into midfield as his ageing legs lost their pace. LB

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 78. Thomas Muller Muller has popped up with important goals for Bayern Munich and Germany throughout his career. The gangly forward has scored nearly 250 goals combined for club and country, which has helped Bayern to eight Bundesliga titles and a single Champions League and Club World Cup. Muller will not be the last player to excel with Bayern and Germany, but he may well be the last sort of his type of player, placing the importance of timing and occupying space above all else in the game. KV

Bongarts/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 77. Mohamed Salah The ‘Egyptian king’ has turned into one of the most feared forwards in world football since joining Liverpool from Roma in 2017. After a torrid time at Chelsea, Salah’s second spell in England brought about a Premier League history as he netted a record 32 goals in 36 league games. The outright Premier League top scorer in 2018 and the joint winner last season, no longer is anyone laughing at the £35m Liverpool paid for him over two years ago. KV

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 76. Diego Godin The kind of defender every one wants on their team and no one wants to come up against. Godin is tough, utterly committed and completely fearless, and at the peak of his powers when Atletico Madrid won La Liga he was probably the best defender around. LO

AFP/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 75. David Silva A midfield maestro capable of playing the game at his pace; speeding up and slowing down while painting a picture amid the frantic action in Premier League games. Silva has never been flustered and can always be relied upon to stand up in the most opportune moments, a cornerstone of the Manchester City era and a candidate for their best ever player, despite the money lavished on various other superstars. JR

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 74. Eden Hazard Such quality in tight spaces and an almost unrivalled ability to dribble at pace, Hazard is capable of true magic, with his best Premier League seasons propelling Chelsea to two titles, and earning . There have been more fallow years, of course, but at his best Hazard has been magnificent, including in helping Lille to Ligue 1 glory in 2010-11. HLC

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 73. Cesc Fabregas The fulcrum of Arsene Wenger’s side following Arsenal’s move to the Emirates Stadium, Fabregas combined vision with genuine goalscoring ability to establish himself as one of the world’s most well-rounded and exciting midfielders. Trophies commensurate to the playmaker’s ability to precisely pick out forwards’ runs more often that not did not come in north London, but two Premier League titles with Chelsea after his dream move to Barcelona failed to live up to expectation were just rewards for the midfielder. Nevertheless, he still won La Liga and the Copa del Rey while in Spain, and was part of the squads that won the 2008 and 2012 Euros as well as the 2010 World Cup. KV

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 72. Deco A player at home in any era who blossomed under Jose Mourinho not once but twice. At home at No 10 Deco effortlessly controlled games for Porto and latterly Chelsea as a key cog in two of the Special One's greatest sides. BB

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 71. Lilian Thuram Enjoyed the best years of his storied career right at the very start of the 21st century, after he moved from Parma to Juventus in a double transfer, along with Gianluigi Buffon. Went on to form a formidable defensive partnership with Igor Tudor as well as Fabio Cannavaro, before a late career swansong at Barcelona. He also won the European Championship with France in 2000. An imperious defender, who now works tirelessly fighting against racism in football and society. LB

AFP/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 70. Nemanja Vidic Warrior. Tough as any Premier League centre-half, totemic at times and a pillar of consistency for Manchester United. Indomitable in the air, his partnership with Rio Ferdinand is perhaps the best English football has seen this century, contrasting in styles but with an innate understanding of each others’ abilities. Superb leader to boot. HLC

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 69. Marcelo The Brazilian is well renowned as one of the best attacking fullbacks in world football, and has been one of Real Madrid’s most consistent performers for a number of years. Arriving at the Santiago Bernabeu as a nervous 19-year-old, Marcelo has lived up to his reputation as Roberto Carlos’ successor at both club and international level, as likely to whip a cross in as he is to audaciously hammer one in from outside the penalty area. Often sporting a smile off the field, Marcelo’s trophy record makes for pleasant reading having experienced four consecutive Champions League victories as well as four La Liga and Club World Cup titles. KV

AFP/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 68. Ryan Giggs While it can be argued his most captivating moments came before the turn of the millennium, Giggs’ longevity was remarkable, never truly fading from the first team at Old Trafford as the brighter sparks came and went. Evolved as football evolved, from teenage tearaway to cultured crosser as the legs slowed. Seven post-2000 Premier League titles, a PFA Player of the Year award and the 2009 Sports Personality of the Year. HLC

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 67. Antoine Griezmann A very modern forward, adept anywhere across the offensive line and a true team player, always ready to defend from the front. But it is ultimately for his ability in front of goal that he secures his place on this list. A revelation at Atlético Madrid and as equally important to the world champions: Griezmann was the top goal scorer as France finished as runners-up at Eurp 2016 before playing a starring role in their triumph two years later in Moscow. LB

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 66. Clarence Seedorf Seedorf enjoyed great longevity throughout his career divided into two decades. The latter of which, spent in Italy, easily earns his place here after gliding across the pitch for AC Milan, shining bright in Carlo Ancelotti's diamond to collect two Champions League titles - clinching four in total and becoming the only player to win the competition with three different sides. JR

AFP/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 65. Wesley Sneijder Sneijder won league titles in Spain, Italy, Turkey and his native Netherlands, as well as the Champions League with Jose Mourinho's Inter Milan, and built a stellar international career to become the most capped Dutch player of all time. But the lasting memory is simply of his natural grace on the pitch, gliding over the field before bursting into life to change any game in an instant. LO

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 64. Gabriel Batistuta A great goalscorer and a scorer of great goals, Batistuta is one of the best strikers ever to have graced Italian football. He remains Fiorentina's top Serie A goalscorer, having spent the majority of his career in Florence before moving to Roma where he finally clinched the title. He is the only footballer ever to have scored a hat-trick at two separate World Cups. LO

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 63. Fernando Torres A captain of Atletico at 18 El Nino was destined for greatness ever since his formative years. While he may never have hit those heights for long enough his Liverpool career where he tortured the very best, notably Nemanja Vidic at Old Trafford, saw him comfortably become the most feared No 9 on the planet. Add in a world crown and two European titles and you have a player who more than earns his place here. BB

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 62. Ruud Van Nistelrooy Perhaps the most natural poacher in the countdown, Van Nistelrooy ended his career with better than a goal every two games and churned out far more through his peak years with PSV, Manchester United and Real Madrid. Most notable was his brilliance at the highest level, three times finishing a season as the Champions League's top scorer. Disputes with Dutch managers hindered an international career that might have propelled him higher up this list. LO

AFP/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 61. Claude Makélélé Few on this list can say they redefined their position but the little French magician did just that. The Makelele role will go down in the annals for any player with any defensive nous whatsoever, but few since have boasted the football intelligence and positional discipline of the man who coined its name. A player far beyond his era. BB

Bongarts/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 60. Sergio Aguero An unbroken streak of relentless goalscoring, spurring Manchester City to four Premier League titles, adapting his game to suit Pep Guardiola's style and resisting the challenges of a fleet of world-class temporaries, the Argentine may yet end his career as the greatest striker in English history. TK

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 59. Cafu Well over a decade on from his retirement anyone even close to resembling a serviceable right-back is still known as the English, Scottish or Welsh Cafu, a testament to a glittering career where he redefined what was expected from his position. A dynamic, attack-minded full-back he was also an esteemed leader and captained his country to the World Cup with typical class in 2002. Anyone remembered as one of Brazil’s greatest players is more than worthy of this list. BB

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 58. Miroslav Klose Only Marta has scored more goals in World Cups than Klose and his supreme record at international level with Germany is what sees him earn his place here. The archetypal target man famously rarely scored from anywhere other than inside the box, but he made the 18-yard area his own in a storied career that saw him score more goals for Germany than anyone before or since. BB

Bongarts/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 57. Kevin de Bruyne A maestro and marshal at the heart of Manchester City's midfield, the Belgian is one of the most inventive, tactically astute and well-rounded players to grace the Premier League. He has won back-to-back league titles, an FA Cup and a raft of individual awards and only injuries have prevented him from casting his influence further. TK

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 56. Henrik Larsson The Swede scored pots of goals for his home town club, Helsingborg, in his early years, and never really stopped until he retired back at his boyhood team. In between he ventured away to write history with Celtic, win the Champions League with Barcelona and even make a memorable cameo at Manchester United. His pinnacle was the season after he broke his leg, when he returned so determined to make up for lost time that he won the European Golden Shoe. LO

AFP/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 55. Xabi Alonso If Roger Federer was a footballer he might have been something like Xabi Alonso: majestic, composed and precise, playing with a wand while barely breaking a sweat. Liverpool fans still adore him and so does everyone else. He was understated, bar those halfway line goals, and that was part of his charm, redefining what a holding role player could be, and he won it all: Champions League, La Liga, Bundesliga, European Championships and the World Cup. LO

Bongarts/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 54. Dennis Bergkamp The player who brought the Premier League to the height of technical grace and artistry, the Dutchman was synonymous with moments of unthinkable ingenuity and other-worldly touches as he pulled the attacking strings in both Arsenal's 2002 double-winning campaign and the Invincibles season. TK

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 53. Gareth Bale Bale’s professional career started terribly, suffering a major winless streak at Tottenham, but once he began winning he barely stopped. His transformation from tentative full-back to galavanting winger brought him to the Premier League’s attention, and his destruction of Maicon at the San Siro introduced him to the world (and probably erased Maicon from this list, come to think of it). Three back-to-back Champions League wins later, including one of the great European goals, and it is safe to say the boy from Cardiff has come a long way. LO

AFP/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 52. Gerard Pique Over a decade at the heart of Barcelona's defence and undoubtedly one of the game's greatest ball-playing centre-backs, the Spaniard has won everything on offer: eight LaLiga titles, three Champions Leagues, countless cups as well as being a leader in both World Cup and European Championship successes. TK

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 51. Robert Lewandowski One of the greatest goalscorers in Bundesliga history after a decade spent between Borussia Dortmund and Bayern Munich, the Polish striker has won seven league titles. His CV might not be as rounded, having spent his entire prime in Germany, but 60 goals in 110 international games are a testament to his unfaltering consistency. TK

AFP/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 50. Javier Zanetti A dominant player with great longevity and versatility. His selflessness, workrate and positional intelligence allowed him to lift a mostly dysfunctional Inter side over the years. But then Jose Mourinho offered a system that could capitalise on Zanetti's legs and reliability; the treble clinched his legacy in a 19-year spell in black and blue. JR

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 49. Didier Drogba While there have been better goalscorers few knew how to pick their moments better than the great Ivorian. At his dominant peak few could touch him as one of the game’s ultimate big-game players. The star of Chelsea’s 2012 Champions League win Drogba remains beloved by Blues fans for two title-winning spells while Jose Mourinho still regards him as one of the best he worked with. Truly the King. BB

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 48. Michael Ballack A proper box-to-box midfielder who would revel in the big games; dominant in the challenge at the heart of the pitch and in either penalty area. A prolific goalscorer given his supreme passing and selfless work, Ballack inspired Bayer Leverkusen to the Champions League final in 2002, before three doubles in four years with Bayern and then four major honours with Chelsea, as well as another Champions League final. JR

Bongarts/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 47. Oliver Kahn An imposing figure between the sticks, Khan was an intimidating opponent for strikers, making them freeze for just enough time to offer himself enough time to narrow the angles and wipe out danger. A legendary figure with Bayern, inluding six Bundesliga titles in the last 20 years, he would also emerge as a leader for Germany and their runners-up finish at World Cup 2002 before a more calculated strategy saw Die Mannschaft become world champions. JR

Bongarts/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 46. Ashley Cole A rarity as England’s one true really world class player, Cole was the planet’s premier left-back for nigh-on a decade. A title winner with Arsenal and Chelsea it will perhaps be the FA Cup where Cole leaves his indelible mark where he lifted the world’s oldest trophy a record seven times. A key player in two of the Premier League greatest-ever sides Cole will be remembered as one of the real standouts of his era. BB

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 45. Pavel Nedved A thrilling wide player able to slice opponents open with darting runs inside and clever movement to give and receive in and around the box. A Ballon d'Or winner with Juventus and the spark for a tremendous Czech Republic side who should have won Euro 2004. JR

AFP/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 44. N'Golo Kante Just quietly doing his job to an outstanding level, Kante inspired Leicester to do the unthinkable, not only enabling a two-man midfield - but doing so alongside Danny Drinkwater on his way to his first Premier League title. Bigger things would await him at Chelsea, where he grabbed another title, and then with France, as he starred in their second World Cup triumph. Not just the finest midfield destroyer in a decade, but with quality and endless stamina to go box-to-box, as he proved under Maurizio Sarri, proving a lot of people wrong in the process. JR

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 43. Kylian Mbappe The youngest player in this list, with barely a career to call upon, and yet already he has demanded a place in its upper echelons. It is not just that he has scored relentlessly for Monaco and now PSG, winning the title in every season of his career to date, or even that he played such a key role in France’s World Cup triumph. It’s that Mbappé is doing things other footballers don’t do, cutting through teams from one box to another with the ball glued to his feet, retiring defenders as he goes. Surely he will be near the very top of this list in a few years’ time... LO

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 42. Alessandro Del Piero A great goalscorer and a scorer of great goals, Del Piero was one of the finest all round forwards Italy has ever produced. As gifted at making goals as he was at scoring them himself, Del Piero retired as Juve’s all-time appearance and scoring leader and a six-time Serie A champion. Oh and he won the World Cup too. BB

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 41. Alessandro Nesta One of the very best in a long tradition of Italian defenders, but Nesta was different. He was never rushed, never angry, never desperately lunging for the ball. Instead he would glide across the pitch and pickpocket unsuspecting victims with a smile, and before they knew it he was gone. At Lazio and then AC Milan he won everything including Serie A, the Champions League, and the World Cup, but winning Serie A defender of the year four times in a row from 2000, in an era of defensive excellence, tells you just as much about Nesta. LO

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 40. Patrick Vieira Remains the gold standard for box-to-box midfielders after dominating the Premier League as the lynchpin of perhaps the greatest side ever to grace it. A complete player Vieira was a class above from the outset with his departure from north London leaving a hole that is still be filled. BB

AFP/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 39. Zlatan Ibrahimovic What can you say about Ibrahimovic that he hasn’t already said about himself? A supreme goalscorer across almost countless leagues his otherworldly natural talent is perhaps only surpassed by his larger than life ego. Though a Champions League crown still eludes him he will one day leave a legacy few can match. BB

Manchester United via Getty Imag

100-1: Century countdown 38. Roberto Carlos The Brazilian arguably transformed what a great full back could be, incessantly roaming forwards, forming a wing to every attack, most notably during his time at Real Madrid. Arguably his greatest years came before the Millennium, but La Liga and a World Cup title still followed. But, perhaps, that’s helped by the allure to one of the most astonishing goals ever scored. TK

Bongarts/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 37. Rivaldo His dazzling best may have come just before the new millennium, but his trophy haul since the year 2000 is remarkable. He played a leading role in Brazil’s World Cup success in 2002 before an extremely profitable stint at AC Milan, during which he won the Champions League, Super Cup and Coppa Italia. And then there are the individual performances. His stunning hat-trick for Barcelona against Valencia in 2001 has yet to be surpassed, and is unlikely to be. LB

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 36. Roy Keane Sir Alex Ferguson once described Keane as the embodiment of his winning attitude on the pitch and that is all the more appropriate because, if the great manager is the figure to have influenced the Premier League more than anyone, Keane is the player to have psychologically influenced the Premier League more than anyone. That really isn’t an exaggeration, not when you consider his longevity, the number of titles he won and his absolutely key role in all of them. MD

Manchester United via Getty Imag

100-1: Century countdown 35. John Terry A divisive figure elsewhere Terry remains Chelsea’s favourite son after a trophy-laden near two decade run with his boyhood club. The living, breathing, life and soul of the Roman Abramovich era Terry was perhaps the best pure defender of his generation with his blend of physical gifts allied with a superhuman will to win making him nigh on unmatched at his peak. BB

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 34. Paul Scholes He was never the star of Manchester United’s side, more the quiet conductor in the shadows, anchoring the midfield, flitting passes back-and-forth, flying into buzzsaw challenges. The Englishman was the anchor of 11 Premier League title-winning sides, a feat bested only by fellow ‘Fergie fledgeling’ Ryan Giggs. TK

Manchester United via Getty Imag

100-1: Century countdown 33. David Villa One of the most clinical forwards of his era Villa will be remembered as one of the key figures of Pep Guardiola’s all-conquering Barcelona side. Equally as adept up front as he was out wide he went on to replace the great Raul with the Spanish national team going to become the top scorer in their history as well as being pivotal to the Euro 2008 and World Cup 2010 wins. BB

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 32. Iker Casillas The man known simply as San Iker began life with Real Madrid as a nine-year old before going on to make 725 appearances for Los Blancos in a storied and success-filled career at the Bernabeu. The all-time appearance leader for Spain to boot Casillas has won every major club and international title he has participated in as a player. An all-time great. BB

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 31. Franceso Totti A true oddity in modern football, the near-cult-like Italian spent 25 years at Roma, playing almost 800 games and scoring over 300 goals, as well as featuring in Italy’s 2006 World Cup-winning side. Perhaps the last true one-club man at one of Europe’s elite clubs. TK

Bongarts/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 30. Arjen Robben A mercurial talent who never truly settled in the Premier League, but for a short spell as Chelsea won the title. The flying Dutchman could turn passive possession into danger in a flash with his exceptional control when running at speed. Injuries plagued his time in England with spells at Real Madrid and Bayern establishing himself as one of the greats of his generation. JR

Bongarts/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 29. Wayne Rooney We all knew he was going to be special from the moment he stunned David Seaman from distance as a 16-year-old, ending Arsenal’s 30-match unbeaten run. A move to Manchester United followed, where he won five Premier League titles, eclipsed Sir Bobby Charlton to become the club’s all-time leading goalscorer, and formed one of the most fearsome strike forces ever seen alongside Cristiano Ronaldo and Carlos Tevez. A modern great. LO

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 28. Raul Gonzalez A prolific natural finisher and one of the greatest Spanish players of all-time, somewhat overlooked due to the riches of talent that quickly followed at Barcelona, Raul was the incisive tooth in six La Liga titles and three Champions Leagues. He has made more appearances for Madrid than any other player in history and, until the arrival of Ronaldo, their highest goalscorer. TK

AFP/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 27. Manuel Neuer The towering Neuer has raised the bar for what is expected for modern shotstoppers across the globe. Widely considered to be the best goalkeeper of his generation Neuer has won the Bundesliga seven times, a World Cup once and even has a German word, Reklamierarm (the arm of objection), named after him. A modern great. BB

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 26. Paolo Maldini Genuinely world class for more than two decades Maldini is remembered as one of the finest defenders in history. A right, centre and most notably left-back 25 trophies in 25 years for his boyhood club see him regarded as perhaps the greatest player in Milanese history. Upon his retirement in 2009 his No 3 shirt was retired in his honour. BB

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 25. Dani Alves Possibly the greatest full back in history, and the evolution of Cafu and Roberto Carlos, the Brazilian won six La Liga titles and three Champions Leagues, before leaving for Juventus and then PSG, adding league titles with both. The complete mould of defence and attack, under the tutelage of Pep Guardiola, he remained untouchable for almost a decade. TK

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 24. Carles Puyol A true titan of centre-backs, the Spaniard was the fortress at the base of Barcelona’s defence, an ever-present rock in six La Liga titles and three Champions Leagues. His influence loomed just as large on the international stage, leading Spain to a European Championship and World Cup. TK

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 23. Frank Lampard A midfielder with the goalscoring record of an elite-level striker. Chelsea’s all-time leading scorer, he hit 22 in a single season in 2009/10, netting a grand total of 147 Premier League goals. Incredibly versatile, deployed everywhere across the midfield in Chelsea blue, before enjoying an unexpectedly profitable Indian Summer at Manchester City. TK

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 22. Luka Modric Rarely seen in a Ballon d’Or winner it’s possible Modric remains somehow underrated with his consistent class perhaps overshadowed by the headline-grabbing achievements of those around him. A veritable genius with the ball at his feet the Croatian combines workrate with wizardry with one of the most creative football minds we’ve seen. An integral role in four Champions League wins sees his legacy as a real and lasting star already cemented. BB

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 21. Samuel Eto'o Extraordinarily prolific for so very long: his electric early form at Mallorca saw him earn a move to Frank Rijkaard’s Barcelona, where he scored 130 times in just 199 appearances. Pep Guardiola took his game to another level in the 2008/09 season, before successful stints at Inter Milan, Anzhi Makhachkala and Chelsea. No player has won the African Player of the Year award more times. Only the second player in history to score in two UEFA Champions League finals. And the first player in history to win two European continental trebles. LB

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 20. Neymar If this list was based on natural talent alone, nobody could argue the Brazilian’s position. His combination of skill and creativity is largely unmatched in modern football, but he has also blared with inconsistency and struggled with persistent injury. He already has two La Liga titles, two Ligue 1 titles and a Champions League to his name, but the lingering feeling remains that a large portion of his potential remains unfulfilled. TK

AFP/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 19. Andrei Shevchenko One of the most deadly strikers in European history, Shevchenko’s peak came at AC Milan where he won the Champions League in 2003 and the Ballon d’Or in 2004. Nothing displayed his supreme composure better than his Champions League-winning penalty, finally setting Milan’s battle with rivals Juventus and writing himself into San Siri folklore. LO

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 18. Steven Gerrard The greatest player never to win a Premier League title? He instead remained at Liverpool, spending 17 seasons at Anfield during which he captained his side to two European titles as well as five domestic cups. An extremely versatile and well-rounded player, who completely remodeled his game as he grew older. TK

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 17. Sergio Busquets The rearguarding totem who cleared the canvas for one of the greatest teams in history to flourish. The Spaniard has been a pillar of Barcelona and Spain’s sides for a decade, winning an astonishing eight La Liga titles, three Champions Leagues, the World Cup and the European Championships. TK

AFP/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 16. Luis Suarez Took a little while to hit the ground running at Anfield, but his contribution to Liverpool’s famous 2013/14 campaign will live long in the memory. The Uruguayan hit an extraordinary 31 goals in 33 matches as Liverpool went so, so close to ending their long wait for a league title. His career then scaled new heights at Barcelona, where he has won a staggering four La Liga titles and the Champions League title, in 2014/15. A complete centre forward, who worked tirelessly, assisted his team-mates and was utterly ruthless in front of goal LB

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 15. Luis Figo One of the most elegant players on our list Figo didn’t ever appear to be moving at the speed of the game. Moreover the game appeared to move with him. Flashy and full of flair he was at home at some of the biggest clubs in the world. One of a select few to move between Barcelona and Real Madrid and famously paid the piggy price. BB

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 14. Philipp Lahm One of the great defenders of the modern era, although defender hardly covers it. Lahm became an outstanding captain both at Bayern Munich and Germany, and became a gifted midfielder under Pep Guardiola’s coaching. A winner of eight Bundesliga titles, one Champions League and one World Cup. LO

Bongarts/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 13. Gianluigi Buffon The greatest goalkeeper of the last two decades. And probably the one before that, also. Holds numerous individual records – going unbeaten for 974 consecutive minutes during the 2015–16 season among the most impressive – and a bulging trophy cabinet including nine Serie A titles (and one Serie B), a UEFA Cup and the 2006 World Cup. The ‘personal records’ section of his Wikipedia page meanwhile extends to 933 words. That takes some doing. LB

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 12. Sergio Ramos The most-capped player in Spanish history, a World and European champion and a four-time Champions League winner Ramos is loved by his own and hated even more by others. Never far from notoriety his truly appalling La Liga disciplinary record may never be matched, nor will his legacy as one of the truly great modern defenders. BB

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 11. Andrea Pirlo The most stylish player on our list – both on and off the pitch – Pirlo played the game at his own pace and with more grace than almost any other ever seen. Perhaps the finest deep-lying playmaker in the history of the game Pirlo’s effortless class will surely endure. BB

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 10. Fabio Cannavaro Rarely has one player so single-handedly dominated an international tournament like Fabio Cannavaro at the 2006 World Cup. He was so impressive for Italy that the nation’s media nicknamed him Il Muro di Berlino – ‘The Berlin Wall’ – for his outstanding performances in the heart of the team’s defence, as they kept five clean sheets and conceded just two goals (neither of which were from open play) en route to victory. But he also enjoyed a stellar club career, vital for both Inter Milan and Juventus before winning two La Liga titles with Real Madrid. LB

AFP/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 9. Kaka The last man to win a Ballon d’Or before Lionel Messi or Cristiano Ronaldo, history will remember Kaka as one of the great dribblers with his six-foot size allied with a uncharacteristically low centre of gravity making him nigh-on unstoppable on the run. At his balletic and barracking peak, one of the world’s very best. BB

AFP/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 8. Zinedine Zidane Zinédine Zidane is perhaps the most graceful player on this list, someone who seemed to glide through matches without ever drawing sweat. Around the turn of the century, after winning Euro 2000 with France, Zidane swapped Juventus for Real Madrid where he was the ultimate Galactico, scoring one of the great Champions League final goals. LO

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 7. Thierry Henry The striker who grasped the Premier League with such electric magnetism and revolutionised the epitome of a modern striker. The Frenchman won the Premier League twice, including the famed Invincibles season, but his prime still wasn’t rewarded with the trophy to match his talent. A move to Barcelona brought further baubles and a coveted Champions League, but by then his best had already begun to fade. TK

AFP/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 6. Ronaldo His light shined bright only briefly in the 21st century, but it was enough to earn a place near the very top of this list such was its brilliance. A relentless goalscorer and mesmerising dribbler, with power, pace, two feet and incredible close control that perhaps only Lionel Messi has matched since, Ronaldo will be remembered as one of the greatest forwards of all time. LO

Bongarts/Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 5. Andres Iniesta Thriving in the freedom created in his childhood tandem with Xavi, the diminutive playmaker was perhaps even more influential to Barcelona and Spain’s success, revving the tempo of Barcelona’s all-conquering side, unlocking defences with ingenious control and vision. He is the most decorated player in Spanish history, with nine La Liga titles, four Champions Leagues, two European Championships and World Cup. TK

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 4. Ronaldinho A player of outrageous God-given gifts Ronaldinho enthralled and enchanted all that witnessed him over a spellbinding career that saw him grace some of the world’s biggest clubs. His toothy, child-like grin belied a footballer who just wanted to play, few before him or since can do what he could do. A genius. BB

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 3. Xavi Hernandez The greatest Spanish player of all-time and, perhaps, the greatest passer of a ball too. Xavi was the metronome and all-seeing eye at the centre of Barcelona and Spain’s rampant success, playing conductor and orchestra to eight La Liga titles, four Champions Leagues, two European Championships and the star of the 2010 World Cup. TK

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 2. Cristiano Ronaldo The boy who sparkled at Sporting became a man at Manchester United and a god at Real Madrid. He set his sights on greatness and hasn’t stopped working since, and now his record speaks for itself: Five Ballon d’Ors, five Champions Leagues, six league titles, one European Championship, 700 career goals – and counting. LO

Getty Images

100-1: Century countdown 1. Lionel Messi Lionel Messi has made the utterly remarkable utterly routine. You only have to watch him in any given match. Messi produces so many pieces of play that would be the highlight of anyone else’s career if they were capable of them. For him, they’re just another moment of a game. It is almost an extra-sensory next level. Some statistics, should you need them: Messi has won 10 (TEN) La Liga titles. Six Copa del Reys. Eight Supercopas. Four Champions League titles. Three Super Cups. And three Club World Cups. He has a gravitational effect on an entire match, to a greater degree than anyone else. The qualities of his talents mean he is always in the centre, dictating, driving.

Getty Images

It was similarly why the 2008-11 Barcelona team genuinely seemed otherworldly when their dominance began. So much of this goes back to the start of that, and a genuinely influential moment towards the end of that decade: Guardiola’s appointment at Camp Nou .

His reimagining and re-introduction of pressing and possession didn’t just disrupt opposition defences. It distorted the entire thinking of the game and began to transform coaching.

It aided the prioritisation of technique development above all else and led to the growth of gegenpressing – literally counter-pressing – in Germany, as well as an ongoing ripple of minor innovation followed by counter-innovation. Coaches moved from developing patterns with the ball to devising pressing patterns without it, and the transition – the speed with which you could get on the ball and produce with it – became key .

This has led to other developments like goalkeepers being able to pass like outfield players and wide players becoming the highest scorers of the team. But the sophisticated combination of so many elements at so many clubs is admittedly down to a combination of other modern factors too.

Modern European football has become a more intense, integrated network of super clubs while the international game has been overtaken and left behind. These clubs attract most of the supporters and the money, so thereby the best players, coaches and ideas. It all just happens at a much faster pace, much like the football itself.

That has ensured the sport is perhaps the most entertaining spectacle it’s ever been, with that itself as a consequence of how attacking approaches have decisively won the philosophical argument that raged in 2010.

That polarity between Guardiola and Jose Mourinho isn’t the only element of the game that looks very different now. So do half of the current super-clubs.

In 2010, Liverpool and Paris Saint-Germain were messes. Juventus were still recovering from Calciopoli, while City were still recalibrating – and simply adjusting – to a takeover that remains one of the most seismic events in football history, not least for its political meaning.

This is something else that has accelerated exponentially in that time: the money in the game. It now sets the agenda, crossing more borders and boundaries than almost anything else. This has also contributed to the politicisation of football, with so many questionable states – from Abu Dhabi to Saudi Arabia to China – now attempting to use the sport to promote their own causes .

That football has become so enmeshed in geopolitics, and imposed upon by proper real-world issues like human rights abuses, is the inevitable price of its massive global popularity – but not the only one. As has been discussed elsewhere, the glorious entertainment at the elite end is directly offset by huge financial struggles underneath and a predictability within the sport as a whole.

Look at the last decade in terms of the winners of the five major leagues: England, Spain, Germany, Italy and France. Of the 50 titles awarded, 32 were won by five clubs: Juventus, Bayern Munich, Barcelona, PSG and City.

European football has never seen such predictability, and that in itself goes beyond the elite. A total of 10 domestic leagues currently have champions that have won at least six in a row.

So many of the campaigns look so similar from season to season, even as the football itself looks so different to 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies