Travelling while black: Why many Americans are afraid to explore their own country

Jim Crow segregation laws varied by county and state, so black motorists didn't have the freedom to play anything by ear

Her mother always smiled – except when the family made its annual summer drive to visit the grandparents in Magnolia, Arkansas. “The smiles were gone while we were travelling,” says Gloria Gardner, 77.

It was the 1940s, and travelling to her parents’ home town was not approached lightly after the family moved to Muskegon, Michigan, during the Great Migration. Stopping for food or bathroom breaks was mostly out of the question. For black families, preparing for a road trip required a well-tested battle plan in which nothing could be left to chance.

There were meals to cook and pack in ice. Sheets were folded and stacked in the car to use as partitions if they were left with no choice but to take bathroom breaks roadside.

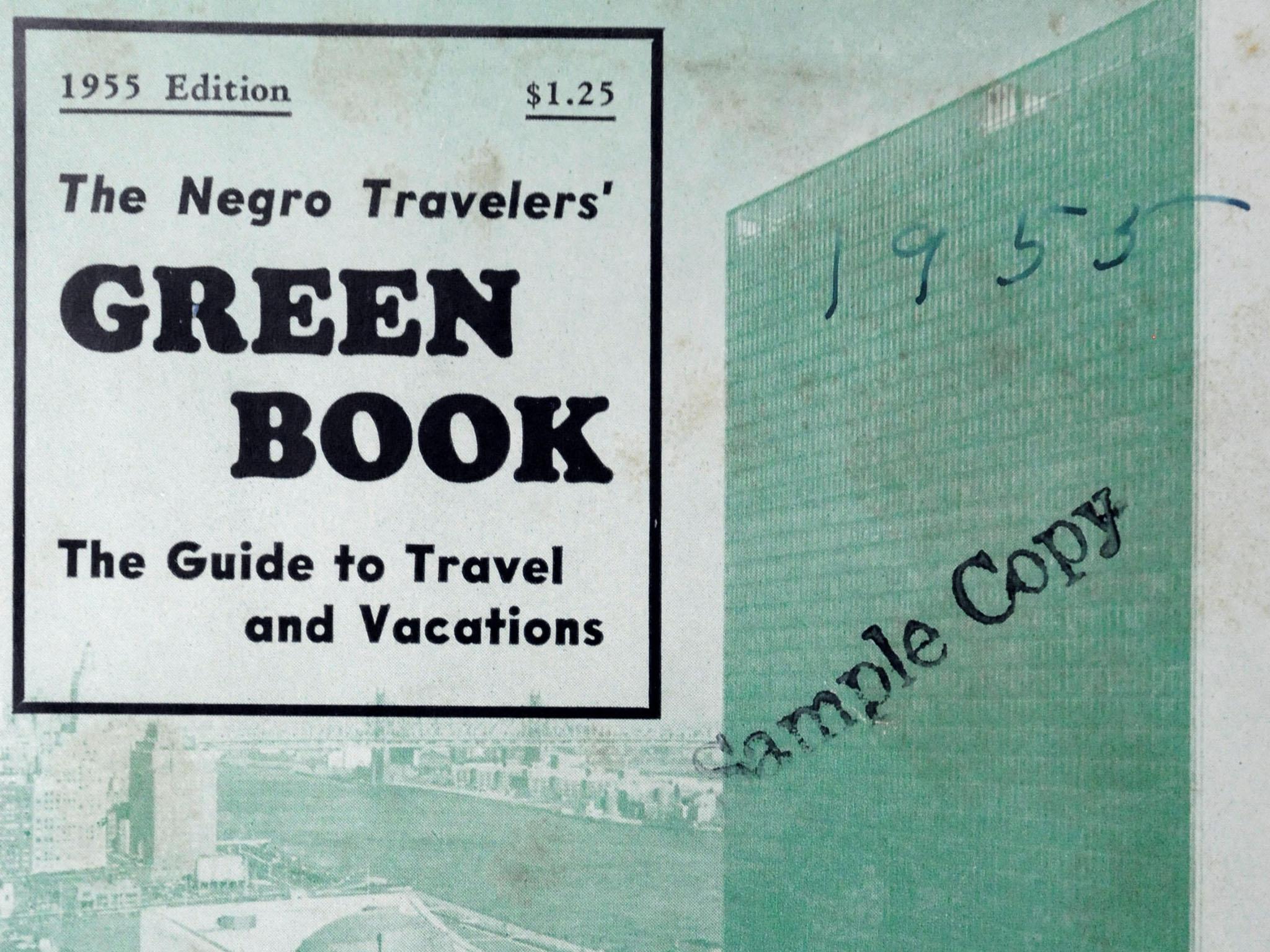

And there was another item that Gardner recalls her parents never forgot to pack: The Negro Motorist Green Book. While her dad drove, her mother leafed through the pages to see whether there were any restaurants, gas stations or restrooms on their route where they wouldn’t be hassled or in danger.

“When it was time to stop, you had to know where to stop,” says Gardner, who now lives in Rockville, Maryland. “If you stopped at the wrong place, you might not leave.”

As she looks through a copy of her father’s 1940 edition of the guide, she recalls its importance: “Our Green Book was our survival tool.”

The Negro Motorist Green Book (at times called The Negro Travellers' Green Book) was created in 1936 by Victor Hugo Green, a postal worker in the Harlem neighbourhood of New York, to direct black travellers to restaurants, gas stations, hotels, pharmacies and other establishments that were known havens. It was updated and republished annually for more than 30 years, with the last edition printed in 1967.

Candacy Taylor, a writer who has catalogued sites in the Green Book that still exist, says Green distributed the guide through postal workers and travelling salesmen. Copies were also sold at Esso gas stations and, starting in the 1940s, through subscriptions.

Jim Crow segregation laws varied by county and state, so black motorists didn’t have the freedom to play anything by ear – food, gas and lodging would probably be off limits during stretches of their journeys. Black travellers risked more than the humiliation of being turned away at restaurants or service stations: they often encountered harassment or physical danger if they inadvertently stopped in the wrong town.

James Loewen, author of Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism, says he has been astounded by his research on the prevalence of “sundown towns”, all-white communities where unofficial rules forbade black Americans after dark. In some cases, signs posted at the cities’ entrances warned black out-of-towners, “N*****, Don’t Let The Sun Go Down On You.”

“I don’t think this is a case of black paranoia for a minute,” he says.

Loewen estimates that the nation had no fewer than 10,000 locales with these rules.

In particular, black drivers in the North had to be on high alert. Sundown towns were a Northern phenomenon, says Loewen, who continues to locate municipalities with such histories.

“In Illinois, I’m up to 507. In Mississippi, I’m at three,” he says.

Although the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ended many discriminatory practices allowed under Jim Crow laws, similar risks and concerns have lingered. Motorists still fear encountering racist police officers or wandering into towns where they’re not welcome. In recent years, travellers of colour have been rejected by Airbnb hosts and booted from a Napa Valley wine tour in a case that led to a racial discrimination lawsuit that was settled.

Ray Jones of Aurora, Colorado, who identifies as African American, says he exercises caution whenever he rides his motorcycle outside of the metropolitan Denver area. He says “White lives matter” billboards and bumper stickers send a message that he’s not totally welcome.

He’s even stopped travelling to North Carolina to visit relatives with his wife, who is white.

“Based on recent events in [Charlottesville] and the climate in America, I will not feel comfortable travelling south of DC for a few [years] when we visit the east coast annually together,” he says.

Evita Robinson, founder of an online community for travellers called Nomadnesstv.com, points to the political climate and a resurfacing of outspoken racism as causes for concern. She says some of her 17,000 members, most of whom are people of colour, say they sometimes feel more comfortable travelling abroad than within their own country.

“Now more than ever, we need each other,” says Robinson, who is black. “We need each other for insights, we need each other for advice on the ground in a community like mine.”

Social media also gives a sense of what domestic travel looks like through the eyes of a person of colour, chronicling stories of discriminatory encounters with such hashtags as #AirbnbWhileBlack and #TravellingWhileBlack. These concerns are not exclusive to black people. Last April, a Korean American woman’s tearful account of being rejected by an Airbnb host because of her race went viral.

In a message explaining her decision, the Airbnb host cited the President: “It’s why we have Trump,” her message read. “And I will not allow this country to be told what to do by foreigners.”

President Donald Trump’s election in November 2016 coincided with a surge in reported hate crimes that month, according to federal data. Though reported hate crimes have steadily declined since at least the 1990s – with 2015 having the fewest on record – reports of vocal white supremacists, high-profile fatal police encounters and caught-on-camera public racism are influencing where motorists of colour are willing to drive.

Dallas resident Jeannette Abrahamson, who identifies as African American, cites the case of a 28-year-old black woman who was found dead in a Texas jail cell three days after she was arrested during a traffic stop.

“What happened to Sandra Bland could have easily happened to me as I’ve made that drive to Houston several times and pass a lot of those small country towns,” says Abrahamson.

During the Green Book era, black drivers were acutely aware that they could be targets of unwarranted traffic stops that could go wrong. Many black men would keep a chauffeur’s hat in the car and tell officers that the vehicle belonged to their white employer, which would often defuse a bad situation.

The chauffeur hat strategy carries hints of the “slave pass”, a note of permission that enslaved people had to carry any time they were travelling alone – evidence that journeys have long been perilous for black Americans.

Traffic stops remain an issue. In a multiyear study of more than 60 million traffic stops across 20 states, Stanford University’s Open Policing Project found that black drivers are not only more likely to be stopped than white drivers, but that black and Hispanic motorists are also more likely to be ticketed and have their cars searched for less cause than whites.

There have been reports of local authorities freely discussing and making light of violence against black people, even advising recruits to shoot young marijuana users if they’re black.

In August, Trump pardoned and offered vigorous support to a former Arizona sheriff who was convicted of criminal contempt related to his racial profiling tactics against Latinos.

Although the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) has existed for more than a century – through segregation and the turbulence of the civil rights movement – the organisation released its first travel advisories last year.

In August, it issued an alert to people of colour travelling in Missouri after a state law was passed making it harder for women and minorities to sue based on discrimination in the workplace. In October, when the organisation advised caution when travelling on American Airlines because of “a pattern of disturbing incidents reported by African-American passengers”, NAACP spokesman Malik Russell says there was an unexpected flood of calls and emails from people sharing stories of discrimination they faced as passengers.

He wonders whether the organisation struck a nerve, revealing how much discrimination while travelling remains an under-discussed topic.

“It was a moment where we saw the need for these types of actions, where it seemed people were waiting for an opportunity to tell their story,” Russell says.

When Taylor speaks about her Green Book research, people often tell her they are relieved that the need for such a guide is over. But she is quick to caution: “It’s so important, I think, that we don’t relegate that as just something that happened in the past, because there are variations of it that we’re still living out in different ways, and it’s just evolved. It’s not gone, in terms of being safe on the road.”

While recalling his own family’s stories of travel during the Green Book-era, Lonnie Bunch, director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, says that, for a person of colour, there’s always going to be an awareness that hangs overhead.

While travel has become easier, he says, “there is always that sense that, ‘Am I going to have the experience that I want, which is to be free of race and to enjoy this moment? Or will race tap me on the shoulder?’ And it usually does.”

© Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies