Hamish McRae: What hope if Germany is floundering?

Economic View

It is spring at last. And on the international financial calendar, that means it is time for the spring meetings of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank – one of the two times a year when the great and the good assemble to debate the state of the world economy.

This time, the overriding theme is the three-speed world, the fast-growing emerging nations, the slow-growing North America, and barely-growing Europe. There is a little sub-theme for Britons, which is whether, given our weak growth, the coalition ought to slow down its deficit-cutting programme.

But while this has obvious political implications for the coalition, in the broad scheme of things, it is a sideshow. In any case, it is bit rum for the IMF to be saying cut more slowly when we are barely in deficit at all, and when it is part of the group forcing far more savage cuts on the weaker eurozone countries.

The really big issue is what on earth is happening in Europe. You don't often get data coming through that is really scary, but we got some last week. It was the car market in Europe in March. In the UK, there were 394,806 new registrations; in Germany, 281,184; France, 165,829; Italy, 132,020 and Spain, 72,677.

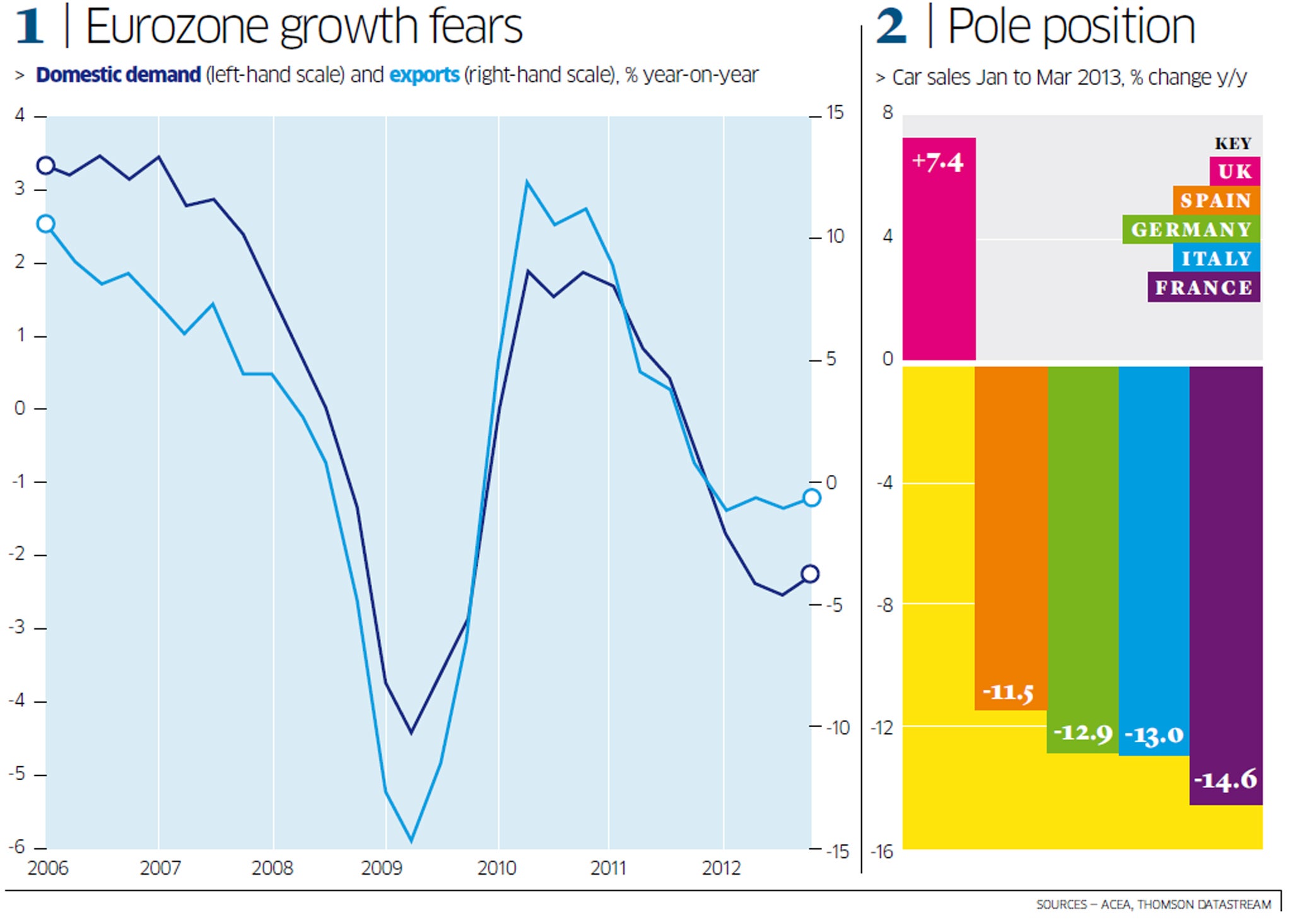

It is true that March is an odd month because in the UK the number plate changes, so there is a surge in registrations. If you look at the first three months of the year, we registered slightly fewer new cars than Germany, as you would expect given our smaller population. So in the right-hand graph I have put the change in registrations for the first three months compared with those in the same period last year. The UK is the only major market to have risen at all. Everywhere else, even in Germany, sales have collapsed.

You can explain why sales are down in Italy (no government), Spain (bust banks) and France (Hollande). But Germany? It is supposed to be the powerhouse of Europe, bailing out all the others and generally bossing the rest of the eurozone around. Suddenly, the Germans seem to be frightened too. I have seen various explanations for this, notably the messy bail-out of Cyprus, but they don't really add up

As for our own economy, whatever the GDP data will say this week, ask yourself whether an economy that has created nearly half a million jobs in the past year and where car sales are up 7.4 per cent is really in recession. I don't think we are growing fast enough, and there are concerns about the future, but common sense says this is not recession. The situation across the Channel, however, could become really alarming.

You can catch some feeling for this from the main graph. It shows domestic demand in the eurozone, together with exports. The scales are different, and during the initial downturn exports fell by far more than domestic demand. But now the position is rather different. Exports are not good but they have not come off a cliff. By contrast, domestic demand is weak, if not quite as weak as in 2009. That leads to two questions. First, what prospects are there for recovery this year? Second, and more important, has something gone radically wrong with the European economy that will condemn it to slow growth even when the cyclical upturn does take place?

On the first, quite a few independent forecasters are even more gloomy than the IMF, which has just further downgraded its forecasts. But I would be inclined to trust the estimates of the Ifo Institute in Munich, which is modestly upbeat about Germany. It thinks growth this year will be 0.8 per cent, a little better than the IMF thinks, and 1.9 per cent next year. If it is right, Germany will be able to keep cutting unemployment and continue to balance its budget. It agrees with the IMF that the eurozone as a whole will shrink this year but thinks that growth next year will be just under 1 per cent.

What ultimately matters much more, though, is the outlook beyond the next couple of years. What difference does the crisis make to long-term West European growth? That question is the title of a paper by Professor Nick Crafts presented at Warwick University earlier this month. One sentence from it is chilling: "Overall, although this is not yet recognised by institutions such as the OECD, it seems likely that the financial crisis will result in a significantly reduced average European growth rate over the period to 2030."

The nub of his argument is that it is quite likely that growth in the euro area to 2030 will be only about 1 per cent a year, by contrast to an average of 2.3 per cent before the crisis. That is partly a result of the debt burden from the crisis, partly the fiscal consolidation needed to cuts those debts, partly demography, partly that the climate post the crisis will push policy away from making the structural reforms needed to boost growth, and so on. For the eurozone, the solution is closer integration coupled with structural reform.

"If deep economic integration is to survive, then a much more federal Europe is required, but this is much easier said than done and will, in any event, take considerable time to implement," Mr Crafts adds.

And us? We have done a lot of the structural reforms that eurozone countries need to do, but must improve the quality of education, repair the shortfall in infrastructure, reform taxation, and reduce the massive inefficiencies of our planning system.

So a lot is to be done. And surely, thinking about this long-term agenda is much more important, and certainly more interesting, than endlessly debating what the IMF thinks or doesn't think about the world economy?

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies