Hamish McRae: Fragile maybe, but it's still a recovery

Economic View

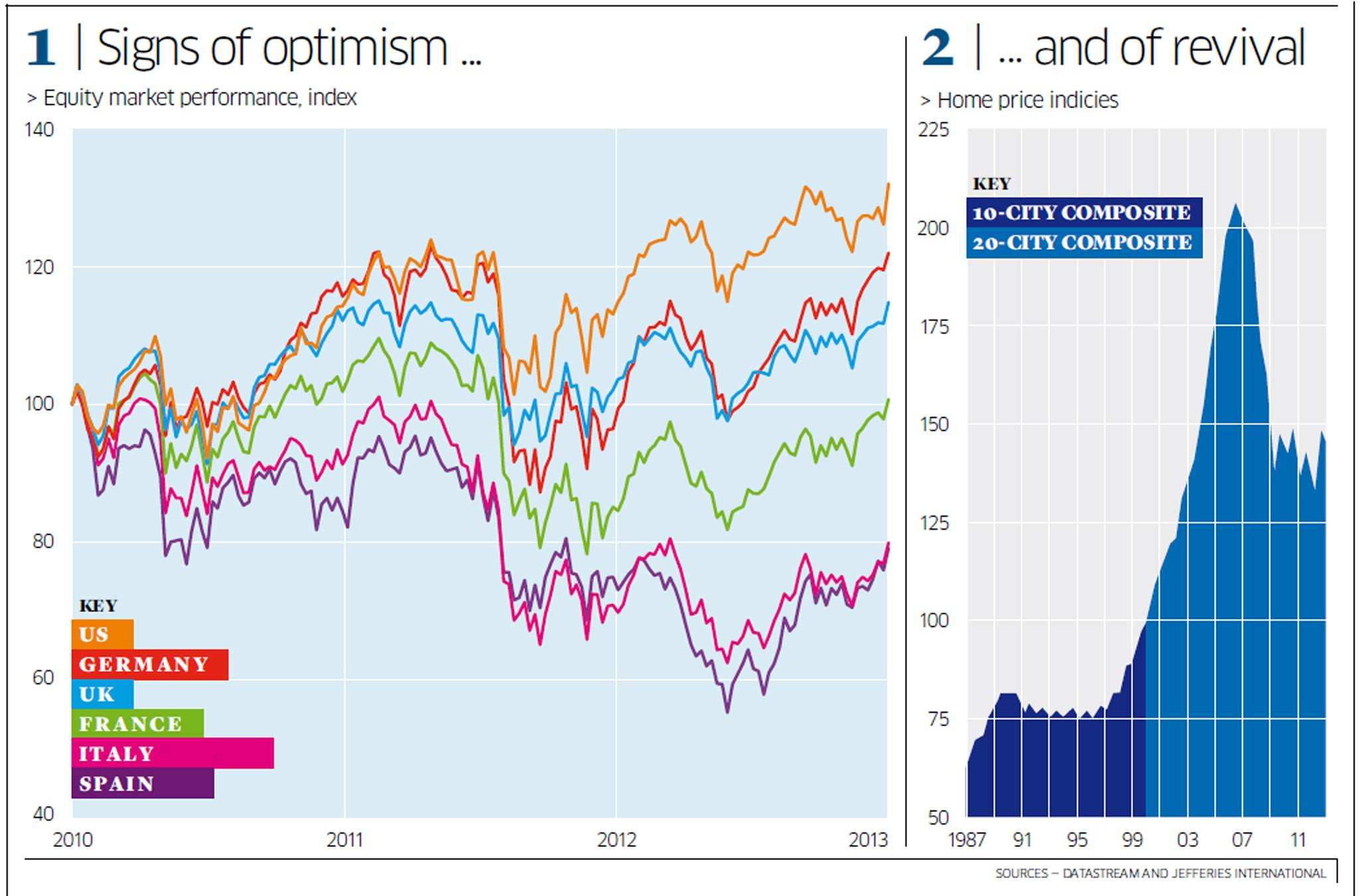

Share markets here and elsewhere nudging new "highs"; economic outlook mediocre. Is this a disconnect, or might the recovery in shares and other asset prices help sustain an increase in real demand?

This is a version of the question as to what extent asset prices reflect and shape the real economy. The answer must be both, but the balance between the two varies over time . For example, in the spring of 2008 shares worldwide were still pretty strong, giving no warning of the horrors to come. They were a reflection of the widespread over-optimism at the top of the boom.

But since last summer share markets have perked up. You can interpret that in several ways. It may be a function of central bank pump-priming: the money has to go somewhere. It may be a growing disenchantment with the ultra-low yields available on sovereign debt, or at least the debt of so-called safe-haven countries. But it may be that share buyers are prepared to look through the probability of a dark spring and see a sunnier summer and autumn ahead.

Over the past three years the main markets have generally reflected the performance of the economies, as you can see from the left-hand chart. You would expect the US and Germany to be at the top and Italy and Spain at the bottom, though maybe the UK market performing better than the French one has more to do with the international nature of companies listed in London vis-à-vis those in Paris, rather than the relative performance of our two economies.

Still, the shares recovery must have some impact on confidence and hence on demand. Here in the UK there is one direct effect: a rise in share prices reduces pension-fund deficits. For companies saddled with under-funded pension schemes this could be a life-saver. But there is a more general point. A rise in share prices will begin to open the rights issue route for companies seeking more capital. Taken as a whole the company sector is cash-rich, but there will be individual firms that are not and no company now wants to be beholden to its bankers.

So does the rise in share prices really add to demand? Marchel Alexandrovich at Jefferies International has looked at this and notes that an European Central Bank (ECB) working paper in 2009 concluded that for the euro area, a 10 per cent increase in net financial wealth increased consumption by 1.2 per cent.

Since the Spanish share prices have risen by 20 per cent since last summer you might expect that to give a 2.5 per cent increase in consumption. But you have to be careful in making hard estimates from incomplete data. I don't think many of us feel more confident about spending more simply because our pensions look a little less insecure.

House prices, on the other hand, in the UK do seem to have an impact on consumption. There is the direct link in equity take-out. During the last housing boom, from 1997 to 2008, Britons supplemented their incomes by increasing their borrowings against their homes. Since then we have been steadily paying back that debt, saving money that might otherwise have been used to boost living standards. That ECB study calculated that changes in house prices in the euro area had a very small impact on consumption, but it may just be another way in which UK behaviour differs from that of our Continental cousins.

I suspect our relationship with property is must closer to that of Americans, and one of the really important issues this year will be whether rising confidence among US home-owners will offset concern about the handling of the fiscal deficit. We don't know what Congress will do but we know it will have a negative impact. We don't know what will happen to the US housing market but we do know that the recovery evident since last summer will be sustained. Historically cheap mortgage rates will see to that.

US house prices are still fairly high by long-term historical standards but they do seem to have bottomed out, as the graph on the right suggests. This shows the S&P/Case-Schiller home price index since 1987. The market as a whole is now back to its level of 2003 and in only two cities, Detroit and Atlanta, are prices still lower than they were in 2000. In New York prices are 65 per cent above their 2000 level and in Washington DC they are nearly double that. So while it is an uneven recovery the US market as a whole is well in its way back to health.

My feeling here is that the US housing market will be the single most important determinant of how the world economy performs this year. It is not just that US consumption is 70 per cent of the world's largest economy. The collapse of the world financial system began because of a collapse in US house prices. So a recovering US market not only helps global demand, it also reduces the property overhang still depressing the world's banking system.

There are lots of reasons to be cautious about the present uplift in financial markets. There are a host of things that can go wrong. These include mismanagement of the US fiscal situation, an economic collapse across southern Europe, Germany back in recession and so on.

Our own situation is precarious, for we have made only modest progress in controlling our deficit and are stuck, unable to reduce it further. More generally the rise in asset prices depends on the various central banks continuing to pump up their respective economies. But to focus on the fragility of the recovery in asset prices is to ignore the impact this recovery has on real confidence, real demand and hence on real growth.

We are not yet in a virtuous circle but we're no longer in a vicious one.

What Hong Kong tells us of London's values

I saw in the New Year in Hong Kong, which ranks alongside London and New York as one of the three most expensive locations in the world.

According to CBRE's tally of super-prime residential property the pecking order is now London, Hong Kong, then New York. For shop rentals per square foot, however, Hong Kong is now No 1, ahead of New York and Paris – London is No 6. For the cost of offices, including rental, taxes and so on, Hong Kong is also No 1, followed by London (West End) and Tokyo. New York is not even in the top 10. Indeed six out of the top 10 office locations are now in Asia.

I was reflecting on this, and in particular on what constitutes competitive advantage in a world with instant electronic communications. People have to live somewhere and it seems the total package that London offer puts it, or at least its glittering centre, ahead of anywhere in the world.

The increases in taxation have hit residential sales in the luxury bracket, which seems to be homes between £3m and £10m, but not the £10m super-luxury end. I suppose too that top-end shop rentals tend to follow top-end home prices, in which case Paris' success is interesting – all those Chinese tourists, perhaps?

But offices? Why is prime location so important? Or maybe the better question is: why is a prime location in Asia so important? My feeling from seeing the glitz of Hong Kong is that in Asia at least, prestige matters. A prime location buys credibility in a way that a suburban location, however efficient, does not. So why is the West End so expensive? Simple: it operates in Asian values, not European or American ones.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies