The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

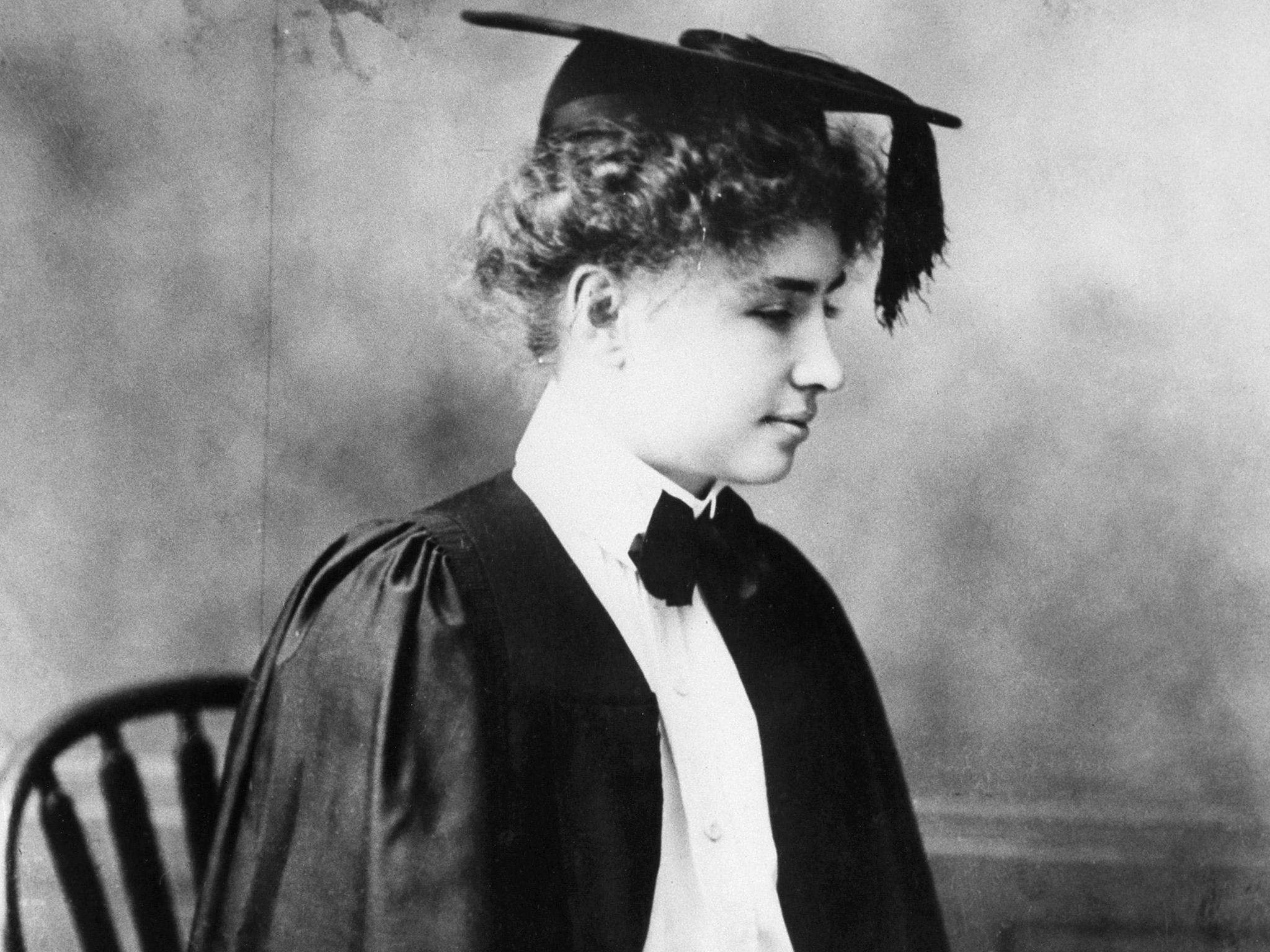

Helen Keller Day: We should never forget the first deaf-blind person to earn a degree

Continuing our column on the lives of ordinary women behind extraordinary stories, this month’s renegade woman was a true visionary, says Harriet Hall

Reading through most accounts of history, we could be forgiven for assuming that women were not the warriors, the great thinkers nor the pioneering scientists who shaped and changed our world.

That men alone birthed art, churned out literature and fiercely challenged the status quo, while women functioned only within the domestic realm. But though the canon has perpetually erased the contribution of women and their work has been systematically discredited, devalued and derided, their light has doggedly broken through the cracks.

“The best and most beautiful things in the world cannot be seen or even touched - they must be felt with the heart,” said Helen Keller.

The American author, lecturer and political activist is celebrated every year on the 27 June.

Surviving an illness that left her deaf and blind as a child, Keller learned to speak, read braille and use sign language with the help from her mentor Anne Sullivan.

She triumphed over adversity to become the first deaf-blind person to earn a degree and went on to become one of the 20th Century’s leading humanitarians.

Keller became a passionate activist, protesting World War I, supporting worker’s rights and advocating women’s suffrage and birth control.

In 1920, she helped found the American Civil Liberties Union.

Read on for an extract from the book She: A Celebration of 100 Renegade Women and to learn about Keller’s extraordinary life.

Helen Keller (27 June 1880 – 1 June 1968, USA), writer and activist

As cold water gushed from the pump onto Helen Keller’s right hand, Anne Sullivan drew out the letters W- A- T- E- R on Keller’s left hand. Using this method, deaf and blind Keller learned over thirty words by close of day.

Keller was just nineteen months old when she contracted a fever that left her without sight or hearing. Desperate to help, her parents took her to the Perkins Institute for the Blind in Boston and there they met twenty- year-old partially sighted graduate Sullivan, who became Keller’s governess and lifelong companion. Sullivan penetrated the loneliness of Keller’s condition, teaching her to read Braille, to sign and to speak. This teaching sparked a love of learning in Keller, who went on to become the first deaf-blind person to earn a degree in 1904, after which she published twelve books.

Keller spent her life campaigning on behalf of the disabled, as well as advocating pacifism, women’s suffrage, reproductive rights and workers’ rights. In 1915, she founded Helen Keller International, an organisation for the blind, and in 1920 she helped found the American Civil Liberties Union. This work earned Keller the Presidential Medal of Freedom and several honorary degrees. She died in 1968, aged eighty- seven. Despite her lack of sight, Keller was a woman whose vision changed the world.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies