The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

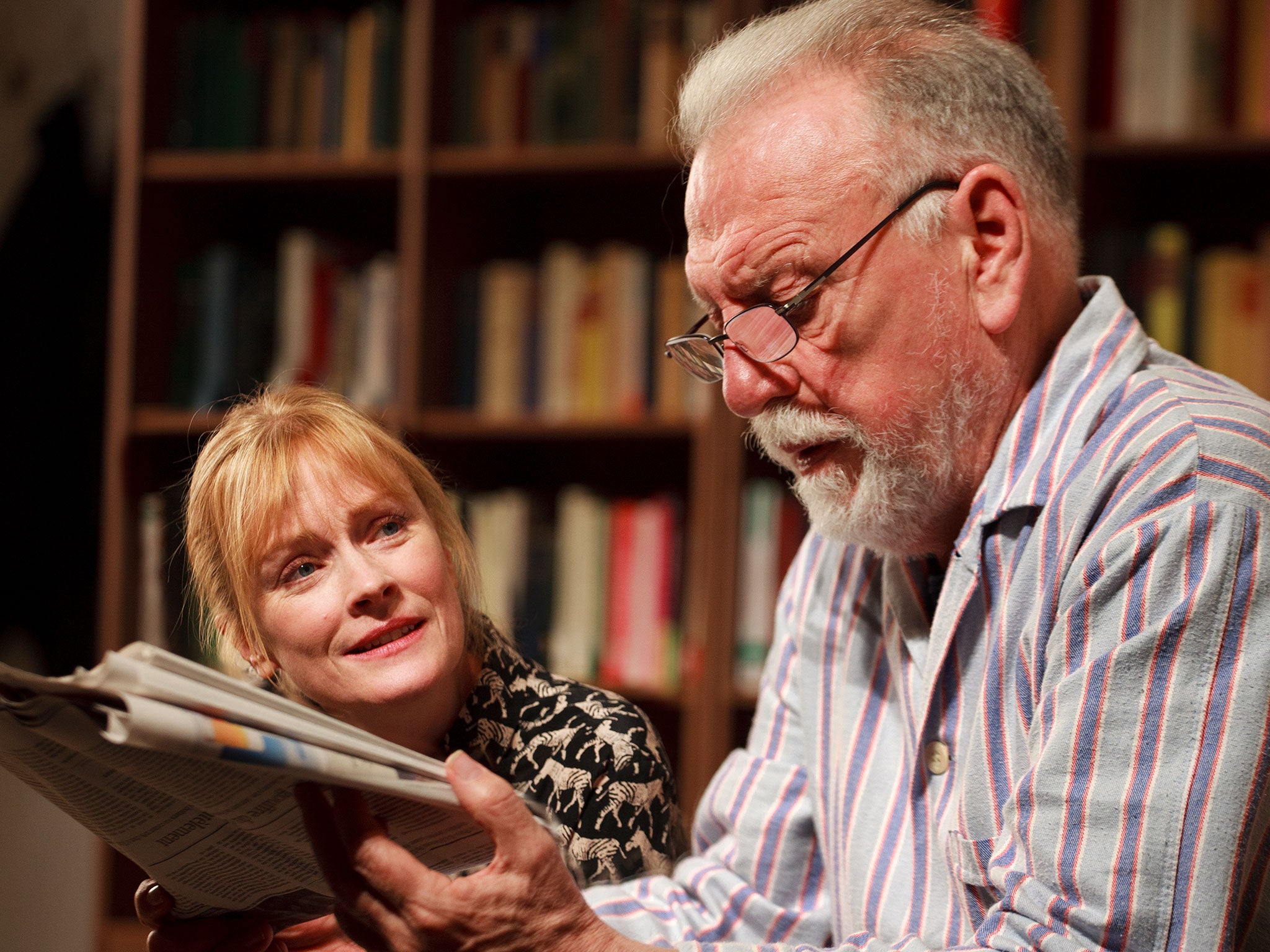

Kenneth Cranham on 'The Father' and why playing an elderly man with dementia has revived his enthusiasm for leading roles

Two parts fruity-voiced luvvie, one part rough-cut Cockney, Kenneth Cranham has been part of the furniture on stage and screen since leaving Rada in the 1960s. Now he is preparing to reprise his award-winning turn in 'The Father'.

Kenneth Cranham is in melancholic mood. At 7.15am on the day we met, he'd lost his friend William Gaskill, the Royal Court's legendary artistic director who'd directed Cranham in several productions during the 1960s and 1970s, including Edward Bond's Saved. The day, before he'd attended a memorial service for Alan Rickman. A couple of years ago he also said goodbye to Roger Lloyd Pack, whom he first met at Rada. “I read a quote the other day that said, 'I'm of an age now that the people I love, most of them are dead, but that hasn't lessened their existence,'” he says, nursing a Bloody Mary at his local in Islington, north London. “I thought, yes, that's what it's like.”

Cranham, a sprightly 71 and dressed today in his customary spotted blue cravat, has another reason for feeling time's winged chariot: he is about to reprise his eponymous role in Florian Zeller's West End smash hit The Father. Cranham's character, Andre, has Alzheimer's; and the play's short, disconnected scenes place the audience right inside his fracturing, disorientated mind. The role has just won Cranham a Critics' Circle award (“my first ever award!” he acknowledges gleefully, if surprisingly) and the play is returning to the West End before embarking on a UK tour. Yet although it is sparking memories of nursing his own father, who had Parkinson's, Cranham isn't finding playing an elderly, befuddled soul depressing: far from it.

“The play is self-energising: it resonates on a universal level,” he says, showing me a crumpled, affecting letter from a stranger who had been moved to write to Cranham about his own father's battle with senility, after seeing the play. “Too many of us know the situation: what are we going to do about Dad? But also, I had been settling down into a series of character roles such as Firs in The Cherry Orchard [at the National in 2011]. Now I'm back playing a leading man again.”

Cranham, who is two parts fruity-voiced luvvie, one part rough-cut Cockney, has been part of the furniture on stage and screen since leaving Rada in the 1960s. He's best known for the television period drama Shine on Harvey Moon, which ran on ITV from 1982 to 1985, but he has also appeared in a string of British films, such as Layer Cake, Hot Fuzz, Gangster No 1, Made in Dagenham and the BBC's Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit. He even popped up a couple of Sunday nights ago as Uncle Mikhail in the BBC's War and Peace. “I wasn't going to take it because it was such a small part, but then all of Barnsbury [the part of Islington that he lives in] saw it, so that was OK.”

But it's in the theatre where his ability to combine menace with vulnerability has flourished. He spent most of the Sixties and Seventies at the Royal Court, which he describes as being like the Groucho Club back then. “You'd get Mick Jagger waiting for Marianne Faithfull, who starred there in Three Sisters. You'd get Samuel Beckett in the bar. You'd get David Hockney, who'd designed the set for Ubu Roi, which I was in. I was the gay boy's favourite back then. I was a very pretty young man.”

Glamorous the Court may have been, but it was also part of a theatre scene fashioning a bleak new vision of England through the strange, violent imaginations of Joe Orton, Bond and Pinter. “To be suited and booted and get to speak lines like something from a Jacobean tragedy,” marvels Cranham of plays such as Loot, The Caretaker and Entertaining Mr Sloane, all of which he starred in. Shakespeare never did it for him: “Too much fat. Whereas you get the opening sequence in The Birthday Party, with the landlady and Stanley, and it's like a dark Donald McGill postcard. And when you come from the 1950s the only sexual expression you could find was in seaside postcards. Those Orton and Pinter plays: they spoke of what I knew.”

Galliard's Shakespeare Theatre site launched as new £750m culture village for London

Show all 10Cranham was born in the small Scottish town of Lochgelly to parents he describes as upper lower class going on lower middle. His father served with the Royal Engineers; his mother was a librarian with a passion for Judy Garland. Lochgelly didn't have much, but it did have two cinemas and the young Cranham would go every night. “I'd pick up a fish supper on the way back. They were magical times.” Later his parents moved to Camberwell in south London, where Cranham failed his 11-plus (“but so did Roger Lloyd Pack”). He didn't do too well at his O-levels either, but by that point he had played Macbeth at school, “which is about six O-levels by itself”, and was intent on becoming an actor.

America never appealed, although he appeared on Broadway as part of his long running stint (“796 performances!”) in Stephen Daldry's garlanded production of An Inspector Calls. “I missed my family too much to want to stay,” he says; by that point he was married to his second wife, Fiona Victory, and they had a young daughter (he also has a daughter by the actress Charlotte Cornwell). He's now gearing up for another long stint as Andre and can't wait to get out on the road. “Theatre is a secular study of humanity,” he says, knocking back his Bloody Mary with a flourish. “It all connects.”

'The Father', Duke of York's Theatre, London, 24 February to 26 March (atgtickets.com); then touring

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies