Luol Deng: 'I love football, but I was built to play basketball'

Brian Viner Interviews: Political refugee at four, Arsenal fan at eight, he has forged an incredible path from Sudan to the lofty heights of the NBA, and all by the age of just 21...

Next month, the National Basketball Association's annual all-star game will take place in Las Vegas, with fans having voted for which five best players from the NBA's 15 western conference teams should take on which five best players from the 15 teams in the east. It is one of the hottest tickets in American sport and yet, improbable as it sounds, votes are raining in for a lad whose formative years were spent in Croydon, and whose overwhelming sporting passion is for Arsenal FC.

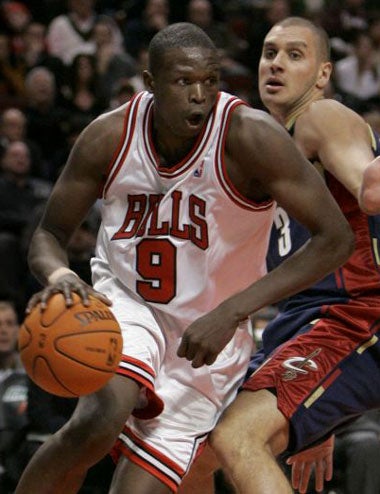

This is the 21-year-old, 6ft 8in Luol Deng of the Chicago Bulls, who sounds as American as Michael Jordan yet considers himself as British as Michael Atherton. The Bulls' No 9 jersey is his, but an even more precious possession is his British passport.

"I just got it," he tells me, with a smile that on a dark winter's night could light up the south side of Chicago. "I played for the English national team while I was growing up, and I was even a spokesman for London's Olympic bid, but I didn't get the passport until a few weeks ago."

Deng's background explains why he so cherishes a simple document. He was born into an affluent family in Sudan, where his father, Aldo, was a prominent politician who had served as minister of irrigation (so important in Sudan that it gets its own ministry), of transport, of culture, and as deputy prime minister. But in 1989 the government was overthrown and sharia law imposed. Aldo Deng, a member of the Christian and mainly southern Sudanese Dinka tribe, was imprisoned for three months, then released and given the unenviable job of conciliating the Christian south and the Muslim north. Fearing for his family's well-being if he failed, Aldo packed them off to Alexandria in Egypt. Luol, the eighth of nine siblings, was four years old.

In Egypt, the family's comfortable lifestyle changed dramatically. While Aldo remained in Khartoum, they had to rely on the charity of the local Catholic church. But it was another benefactor with whom the lives of several of the children became entwined.

Manute Bol, who played for the Philadelphia 76ers and Washington Bullets in a 10-year NBA career notable mainly for his astounding height, even by American basketball standards, of 7ft 7in, was on holiday in Alexandria when he saw some of the Deng kids throwing a ball around, and took them under his considerable wing. Bol was a fellow Dinka, a tribe which, as you'll have worked out, tends to produce prodigiously tall people. In due course he would stoop to light the touchpaper under Luol Deng's NBA career.

But the family's next move was to England. In 1993, with Sudan ravaged by civil war, Aldo arrived in London claiming political asylum. It was granted, and he arranged for his wife and children to join him.

"I don't remember much before then," Deng says. "Nothing at all from the Sudan, and not much from Egypt. Most of my memories start in London. I remember that the city seemed very clean, very advanced. I remember looking out from the plane and seeing the roads and the cars, and in the airport seeing those electric stairs going up and down." Escalators? A merry laugh.

"Yeah, that's it, escalators. It was like stepping into the future. And at the start the British government gave us a house in Wimbledon, with enough rooms for everybody."

And high ceilings? This time Deng does not laugh. I'm not sure he likes even the most benign teasing about his height, perhaps because it made him stand out at his English primary school, where he was quite different enough already. "No, normal ceilings," he says. "Not everyone in my family is tall. One sister is 5ft 3in, and my mum is 5ft 4in."

Deng spoke scarcely a word of English when he started at primary school. At home he spoke a hybrid of Arabic and Dinka; at school he said hardly anything. But by the time he enrolled at St Mary's high school in Croydon his English was fine, and in the language of the playground - football - he was fluent.

"I was pretty good," he says. "I really thought I was going to be a footballer. I loved football and I loved Arsenal from day one. I had all the posters of Ian Wright, but I never went to Highbury. I couldn't afford a ticket, and I was worried about the violence and all that. For a time we lived in Norwood Junction close to Crystal Palace's stadium, and sometimes I'd come home from school and see a bunch of guys, like, smashing a phone booth or whatever. When you're young these things worry you. I decided I'd be better watching on TV."

Deng's rising stardom has enabled him to make up for all that lost time not watching Arsenal in the flesh. "I went back to London the summer before last and heard that [Thierry] Henry is a big basketball fan. So I went to see him at Arsenal's training ground and found out that Philippe Senderos is a huge fan, too. His brother [Julien] plays for the Swiss national team, and we have become very close. I guess I speak to him or text him every other day, and if we make the play-offs he says he might come out, because there's no football this summer, no World Cup or European Championships."

It is disorientating to hear such informed talk of football in an inner sanctum of NBA basketball. We are sitting in the Bulls' locker room in Chicago's United Centre after Deng and his team-mates have thumped Milwaukee Bucks 110-85. It wouldn't happen at the Emirates Stadium, but American sport is admirably relaxed about giving access to accredited journalists, such access indeed that there are players wandering about in or very close to the buff. The genteel Sky Sports press officer, Katie, who has organised my trip and is with me in the locker room, doesn't know where to look. Or perhaps, doesn't know where not to look.

Deng, meanwhile, professes himself happy with the way his sporting career turned out, as well he might with a $69m (£36m), six-year contract reportedly being dangled before him. "With my body I'm better off playing basketball," he says. Inevitably, there came the point when he had to choose balls, and with his brother, 6ft 11in Ajou, playing basketball for the Brixton Topcats, that's where he went.

His hoop dreams gathered momentum when, with the help of Manute Bol, he was awarded a scholarship by Blair Academy, a high school in northern New Jersey with an excellent basketball record. So he emigrated again, aged 14, this time without the comfort blanket of his family. The homesickness was acute, and not even the Ian Wright posters made him feel better, but his basketball flourished and by his senior year he was considered the second most promising high school player in the country, behind a boy in Akron, Ohio, LeBron James, now a superstar with the Cleveland Cavaliers.

While James moved straight from high school into the NBA - and promptly became Rookie of the Year - Deng decided that his immediate future lay in college basketball. No filling in the US equivalent of Ucas forms for him: he was courted by more than 100 colleges before choosing Duke University in North Carolina, another fertile breeding ground for basketball players.

After making a considerable impact in his first year he declared himself available for the NBA draft, rather to the disgruntlement of some Duke fans, who accused him of dollar- grabbing betrayal. Deng responded with the mature equanimity of a young man whose family had experienced civil war a lot more recently than the good folk of Durham, North Carolina.

"Most kids go to school to find a job to eventually support their family, and support themselves," he said. "I put myself in that position in one year, so there's no need to stay the next three."

The draft, an only slightly more sophisticated version of the way football teams are picked in the school lunch hour, traditionally takes place in Madison Square Garden. There it was, in the summer of 2004, that Deng sat wondering where his future lay. With the Chicago Bulls, was the thrilling answer, the team synonymous with the one player whose fame had penetrated even the southern Sudan of his early childhood, Michael Jordan. The Bulls offered $6.3m (£3.2m) over the next three years, and have been well rewarded. His points-per-game average is an impressive 17.6, and against Cleveland a fortnight ago he netted a career-best total of 32. He is a hot property and getting hotter.

As for his high salary that a year from now will be downright stratospheric, I ask him whether he feels an obligation to subsidise everyone in his huge family? It is an impertinent question and does not altogether deserve the elegant answer it receives.

"That comes without thinking," he says. "I don't feel like it's a burden on my shoulders to help them, because it's not my money, it's our money. The one reason I am who I am is because of them. So the way I see it, they deserve it just as much as I do."

The other really deserving cause in his life is the blighted Sudan, even though he has not returned since he left so hurriedly 17 years ago. "My dad is out there running my foundation and trying to help people. I am really passionate about promoting awareness of the Sudan, and my basketball allows me to shine a light into a place which for a lot of years was in the dark, to, like, bring some attention. I did a commercial here for the World Food Programme, and my mum told me that the house where I was born had actually been sold to the World Food Programme, as, like, a place to store grain and stuff. That just blew me away. I mean, wow, that's amazing, right there."

Just as it was disorientating to hear a freshly showered young man in the Bulls' locker room talking about Arsenal, so it is disorientating to hear him using the vocabulary of 21st century American youth - "like" this, and "like" that, and "wow, that's amazing right there" - to discuss the problems facing the Sudanese. But then disorientation is very much part of Deng's story, and the way he has coped with it - in Egypt, in London, in New Jersey - is to his everlasting credit. Whether dealing with it gave him strength of character, or whether strength of character enabled him to deal with it, is a moot point.

Either way, character has become one of his great assets on court. Later, on the internet, I read the following testimonial, written in his rookie year: "There is every indication that Deng production will only increase as the season goes on. One of his major strengths, besides his NBA-ready body at 6'8", and a 220-pound frame including a 7' wingspan, is the mental aspect to his game. Coaches are impressed by Deng's ability to adapt to each basketball game, which is in some ways fuelled by his solid work ethic and his willingness to learn."

With the salvation of one of the most benighted regions of the Third World as his motivation, it is no wonder his work ethic is solid. I ask him, finally, where he feels he comes from.

"No matter what, I'm always Sudanese," he says. "You can tell when you look at me. But I feel English. I want to lead the Great Britain team in the 2012 Olympics. I'm not pushing Sudan out of the way. It just so happens that my dad tried to save his family and we were lucky that Great Britain recognised our situation."

In an age in which "asylum-seeker" has become a dirty word, it is an uplifting and salutary tale.

The NBA is covered by Sky Sports. 'Slam Dunk Monday' is live on Sky Sports 2 on 15 January

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies