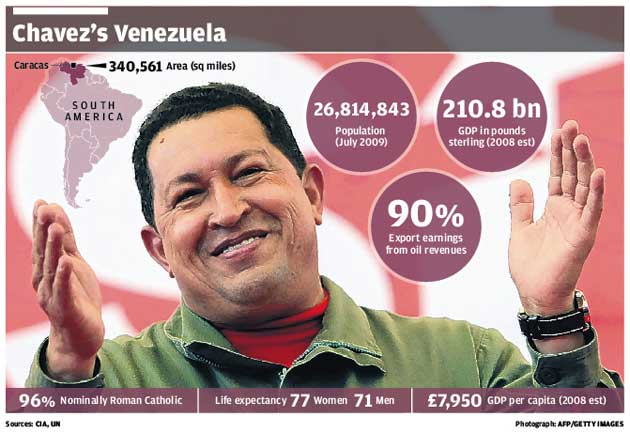

The Big Question: Is Hugo Chavez guilty of wielding excessive power in Venezuela?

Why are we asking this now?

A group of radical supporters of the Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez have attacked an opposition TV channel, Globovision, including by firing tear gas. It comes just as the Chávez government has adopted a series of measures to control the media. Some 34 radio stations have been closed for "irregularities" and 200 more are "under investigation". Critics say it is an assault on free speech by the man who the leftist New Statesman once placed near the top of its list of "Heroes of Our Time". Yesterday the former Foreign Office minister Denis MacShane suggested that it was now time for the Hooray Hugos to give up their uncritical admiration for Chávez after the South American proletarian hero announced a law that could jail journalists for up to four years if they divulged information against "the stability of the institutions of the state".

How authoritarian is he?

In 2006 he withdrew the terrestrial licence for Venezuela's second largest TV channel and replaced it with a state network. But then the station had, along with all the other privately-owned channels, backed a United States-inspired coup against him. Then, earlier this year, he persuaded voters to lift the two-term limit on the presidency – enabling him to keep standing indefinitely for the job. Opponents criticised him for having a second referendum on the subject after the first one failed. (A trick he perhaps learned from the EU's second plebiscite in Ireland over the Lisbon treaty). But an impressive 70 per cent of voters turned out, and 54 per cent said "Yes". Chávez announced: "In 2012, there will be presidential elections, and unless God decides otherwise, unless the people decide otherwise, this soldier is already a candidate," he told his supporters. "I am ready!" Critics say Chávez is hollowing-out Venezuelan democracy, though his supporters point to Germany, which allows for re-election indefinitely (Chancellor Helmut Kohl was in power for 16 years before losing his fourth election) without any major threat to German democracy.

What about human rights?

The lobby group Human Rights Watch has been critical of Chávez's expansion and toughening of penalties for speech and broadcasting offences. It has accused him of a disregard for the separation of powers, with attacks on the independent judiciary and on workers' rights to associate freely. The Venezuelan police have never sunk to the levels of barbarity of places like Brazil and Argentina at their worst, but it is said that those who don't tow the chavista line can be excluded from state jobs or benefits.

So why do Venezuelans keep voting for him?

Because, for all his faults, Chávez is a lot straighter and more honourable than the corrupt and kleptocractic regimes that preceded him. They also like his flamboyant and ribald style, which is on show not just in big set speeches but in his own live TV talk show Aló Presidente. Over the last 10 years there have been 14 referenda and elections and he, or his party, have won 12 of them. Chávez is generally viewed as speaking and acting in the best interests of the poor. Though his opponents dub him a dictator, Chávez keeps getting re-elected – and with very high turnouts in elections praised as free and fair by international observers such as the EU.

Have the poor benefited?

Undoubtedly. Chávez has channelled billions of dollars into social programmes in the form of health and literacy programmes aimed at the poorest. There is free dental care, free health, access to education and vocational training, social housing and cheap food subsidised by the state. There are elected neighbourhood community councils, which decide how government money will be spent locally. There are 3,500 local communal banks for micro-financing. The incomes of the poorest have risen by 130 per cent. Social indicators, on child mortality, disease, illiteracy, malnutrition and poverty, show huge improvement.

Things are far from perfect – state control of food prices has led to sporadic shortages. But the net improvements are clear. Official UN figures show that poverty has dropped from 51 per cent to 25 per cent since 2003. Extreme poverty is down from 25 per cent to just 7 per cent. Venezuela is well on the way to reaching its first Millennium Development Goal years ahead of schedule – in stark contrast to those Third World countries relying on the affluent West for aid.

So who exactly is against him?

The vested interests who depended on the old corrupt economic model for handling the country's oil economy, which is the fifth largest in the world. Also the professional and middle classes who relied on the working of the old elitist model. Prominent among these are the owners, managers, and commentators workings on the five major private television networks and largest newspapers who have opposed Chávez for a decade. Their airwaves and pages are full of day-to-day issues like muggings (crime is high in Venezuela) and the price of milk. But their real concern is the shift from alignment with the US-dominated globalised economy to the bilateral trade and reciprocal aid agreements which Chávez has called his "oil diplomacy" – bartering oil for arms with Brazil, for doctors and other expertise with Cuba, and for strapped meat and dairy products from Argentina.

They were also alarmed by Chávez's wider proposals as part of a constitutional reform including limiting central bank autonomy, strengthening state expropriation powers and providing for public control over Venezuela's international reserves. It is measures like that which have caused Washington to massively subsidise Venezuela's opposition parties.

How has the arrival of Obama changed things?

The United States has long seen Chávez as a threat. In the Bush era it backed a botched military coup against him and, at the same time, criticised him for "undermining democracy". Chávez was applauded in 2006 when he referred to President George W Bush in the UN General Assembly as "the devil". But the arrival of Barack Obama has robbed Chávez of his anti-American card. He is now talking of re-establishing diplomatic ties with the US.

What impact is the recession likely to have?

Chávez's critics say he is buying his popularity by squandering the nation's oil wealth on social programmes which are transitory and will bring no lasting change to underlying structural problems. With the fall in oil prices they predicted doom would follow.

But that was when oil was $40 a barrel, and they knew that Chávez's budgeting was predicated on a world oil price of $60 a barrel. Yesterday the price was $71 and even the cheaper Venezuelan crude oil was $63. There may also be something of a longer-term structural problem. The private sector is shrinking relative to the overall economy. Millions more Venezuelans depend on the state for jobs and handouts than a decade ago. But the oil will not run out before Chávez's time in power is well over, however long he might extend it.

Is it time to give up faith in the President of Venezuela?

Yes...

* His violations of human rights are becoming more authoritarian as the years pass.

* He is squandering vast amounts of oil wealth on social security programmes that are only a sticking plaster on deep structural woes.

* Constitutional changes allowing him to rule indefinitely are dangerous.

No...

* He has massively improved the lives of his country's poorest people.

* His foreign policy remains an important challenge to the power of the US in the region.

* Venezuelans still support him far more than voters in democracies like the UK or US support their leaders.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies