John Clark interview: Transatlantic kidnap saga that put extradition treaty on trial

When Eileen Clark was put on a plane and sent back to the US, she was seen as the innocent victim of an abusive husband and an unfair law. In his first interview, her estranged husband tells David Usborne why her defenders were wrong

John Clark came closest to crumbling in 2001. It had been six years since his first wife, Eileen, had vanished with his three children from their New Mexico home and he still had no clue where they were. “I am not going to make it, I have missed my chance to find them,” he thought. He couldn’t know that finding them would be only the half of what lay ahead.

His has been a passage of pain and frustration that in the end was to last almost two decades. Some of its turns he remembers more keenly than others. The day he went on Dr Phil, a US talk show, in the desperate hope that the exposure would help ferret out his lost family. The afternoon in 2008 when he was up a ladder at work for his window blinds company and a call came to say they had been found, not in America but in Oxford, England.

Other stages in the story took longer, like the protracted and ultimately doomed efforts by Ms Clark after she was arrested in 2010 to fight extradition by the UK to the US to face trial. The success of a visit to New Mexico by his two sons, Chandler and Hayden, now 27 and 24, that Christmas and the subsequent loss of that connection as they turned their backs on him again. And there was the British press coverage. Oh yes, he remembers that too.

The past few days have been better. Last Thursday he and his second wife, Jeanette, put on their best and drove to the federal court in downtown Albuquerque to witness what was, to all intents and purposes, Ms Clark’s final, sad surrender. She had agreed, in return for a reduced sentence, to change her plea to guilty on one felony charge of “international parental kidnapping”. “Guilty, your honour” she murmured. The deal needs final approval by her trial judge, but her punishment will be 12 months’ unsupervised probation. She will be returning to Britain soon.

Mr Clark had little opportunity to savour the moment. For a brief second, as lawyers gently guided his ex-wife out of the courtroom, her eyes seemed briefly to skitter to the public gallery where he and Jeanette were sitting, then shot back straight ahead again. “She wouldn’t look at me,” Mr Clark agreed later. “She will not look at me.”

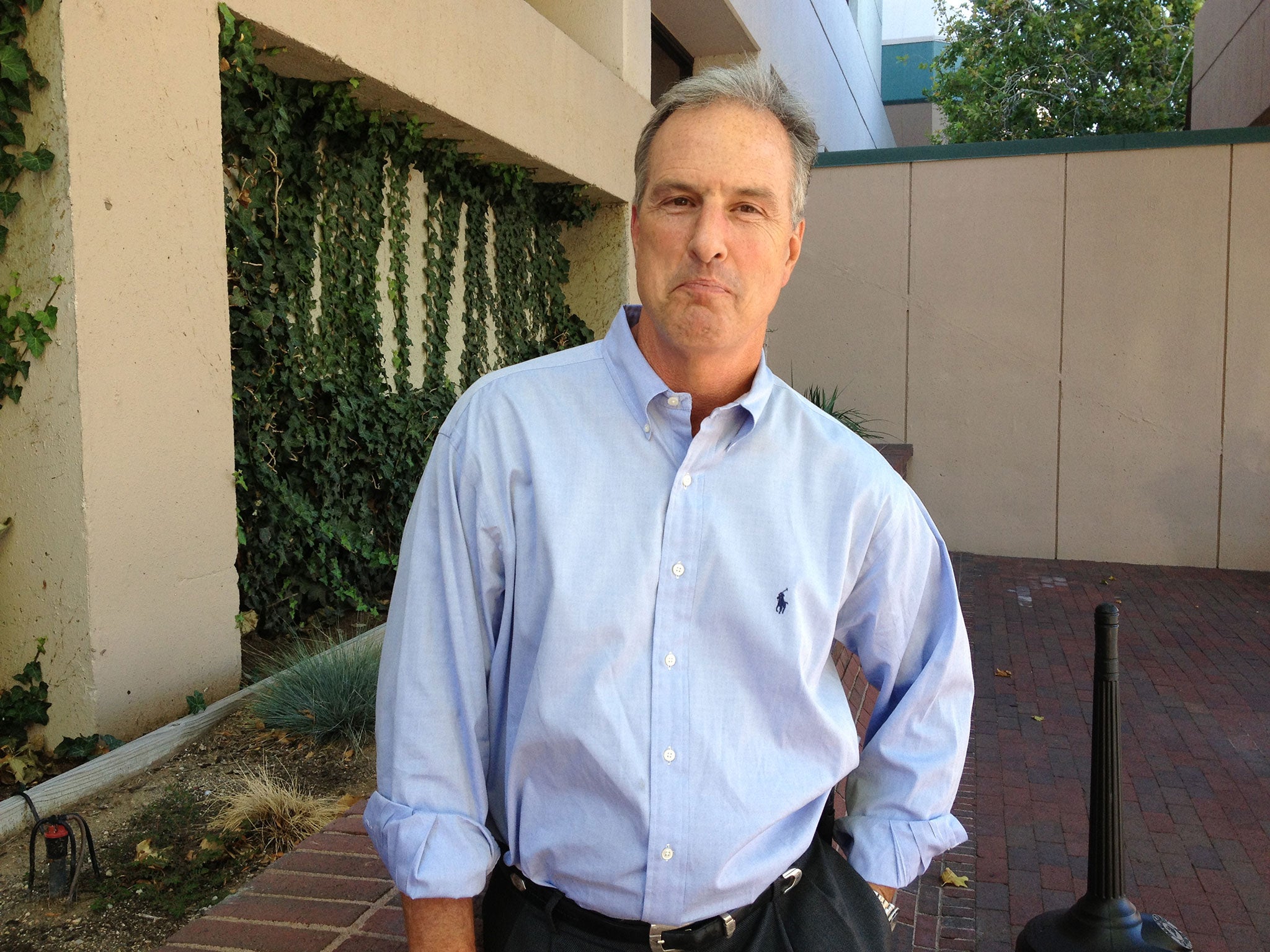

At lunch after the hearing and then later in his window blinds showroom in a northern suburb of Albuquerque, Mr Clark tried hard to explain his feelings at that moment – and during all those long years before – to The Independent. It was something, he admitted, he hadn’t done before, except with Jeanette. He said he hadn’t cried in those years either, yet as he talked on this day he welled up again and again, Jeanette feeding him tissues.

As to the plea deal, yes, there was satisfaction, he said. He mentioned “conclusion”. He also spoke of “vindication”, but tripped on his tongue and said “vilification”, a word he clearly wanted to get out there too.

When Ms Clark took off from the marital home in February 1995 with their two boys, then aged seven and five, and their daughter, Rebekah, just two, she wrote a note to her parents in Atlanta saying she was leaving because she was in fear for her life. Soon after, she arranged legal depositions from assorted “friends” and relatives describing the “abuse” she had suffered at the hands of her husband. People, by the way, he had barely heard of.

“They are just lies,” Mr Clark said, producing reports from two lie detector tests he took denying the charges. “There was no physical abuse, there was never any. There are no police reports, I have never been arrested. I was being falsely accused. It was about my reputation, it was about me.” That should be clear now, he said. “Do you think she would have pleaded guilty, if she could prove this? She can’t prove it and I have nothing to hide.”

Today, Mr Clark surmises two things about his ex-wife’s actions. She was afraid that a history of depression would deny her custody of the children if she had simply asked for a divorce, and she fabricated the abuse claims so she would have a defence in the event that either Mr Clark or the authorities attempted to pursue her.

And indeed she was to resurrect them when her arrest did come and she sought the support of civil liberties groups in Britain. Foremost among them was Liberty, which led the chorus of disapproval when the British Government acquiesced to the extradition request from the US. Liberty and other groups portrayed Ms Clark as a victim of the US-UK extradition treaty and, by and large, the British newspapers bought into the narrative.

In particular the ferocity of Liberty, otherwise known as the National Council for Civil Liberties, took Mr Clark by surprise. “These women’s groups want to turn this on me: I am an angry guy, she has got to face her abuser. First of all I am not her abuser. And I didn’t bring these charges, the United States government sought to bring her back for kidnapping.”

He also wants to know if there is a “gender bias” involved; that women and mothers get the benefit of the doubt in such cases, never the men and fathers. “A lot of men out there are falsely accused and we don’t have a bunch of guys running around trying to represent us,” he said. Certainly he thinks he saw a gender bias in the way the saga was reported in the British press. He came to Britain for one extradition hearing, yet he said he received almost no requests to tell his side of the story.

“It’s not quite right that when a man has his kids taken away from him and then she comes out with lies and insinuations that all of a sudden they take her side,” he said. “I am the person who lost my kids, she is the one who’s had them the last 15 years, and all of a sudden I am the bad guy? I see that kind of gender bias.”

Mr Clark, 54, seemed almost taken aback by how emotional the interview was for him. “I guess it’s just the day,” he said, referring to the court action earlier. “I have just put my whole life in your hands.” But he insisted that anger was not what he was feeling, and nor was punishing his former wife his first interest. It was all about his lost children. The boys are again not talking to him. He hasn’t seen Rebekah since she was two, or spoken to her. He’s got one letter.

To any father, especially any father whose family has splintered, Mr Clark’s agony is obvious. Whether out of loyalty to the one parent who raised them, or because they couldn’t see through the noise of the press, he said they didn’t know what he had suffered. More importantly, they couldn’t know how much he loved them; had, in fact, mourned for them.

“It was a death” when they were gone, he said. “I didn’t realise it was a death until probably about a year ago, when I knew all the damage that was done. The lying and the conniving – the not being honest about what happened.” When Ms Clark left she took nothing (aside from the contents of her bank account), not even toys “or her bible”. He kept the children’s bedrooms exactly as they were for almost five years. Purely out of hope.

Why was he now talking to The Independent? He wasn’t, he was talking to his children, who would read this. He wanted them to understand; if not now, one day. As he said this his voice took on an urgent, exasperated tone. “Do you understand the significance of this plea? Do you understand that if she wanted to go back to the UK, if she spent one minute, one second, one day of incarceration in this country that she’d never have been able to enter the UK again?”

He explained: the prosecution told him early last week that a plea deal was an option and that it meant his former wife accepting responsibility but also being spared prison time. She would be able to go home and reunite with her – his – children. He could have blocked it. He didn’t. That was his gift, right now, to his children.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.