Stargazing in November: Mercury to cross the face of the sun for last time in 13 years

Mercury will appear as a small black dot during its eclipse of the sun, occurring 11 November

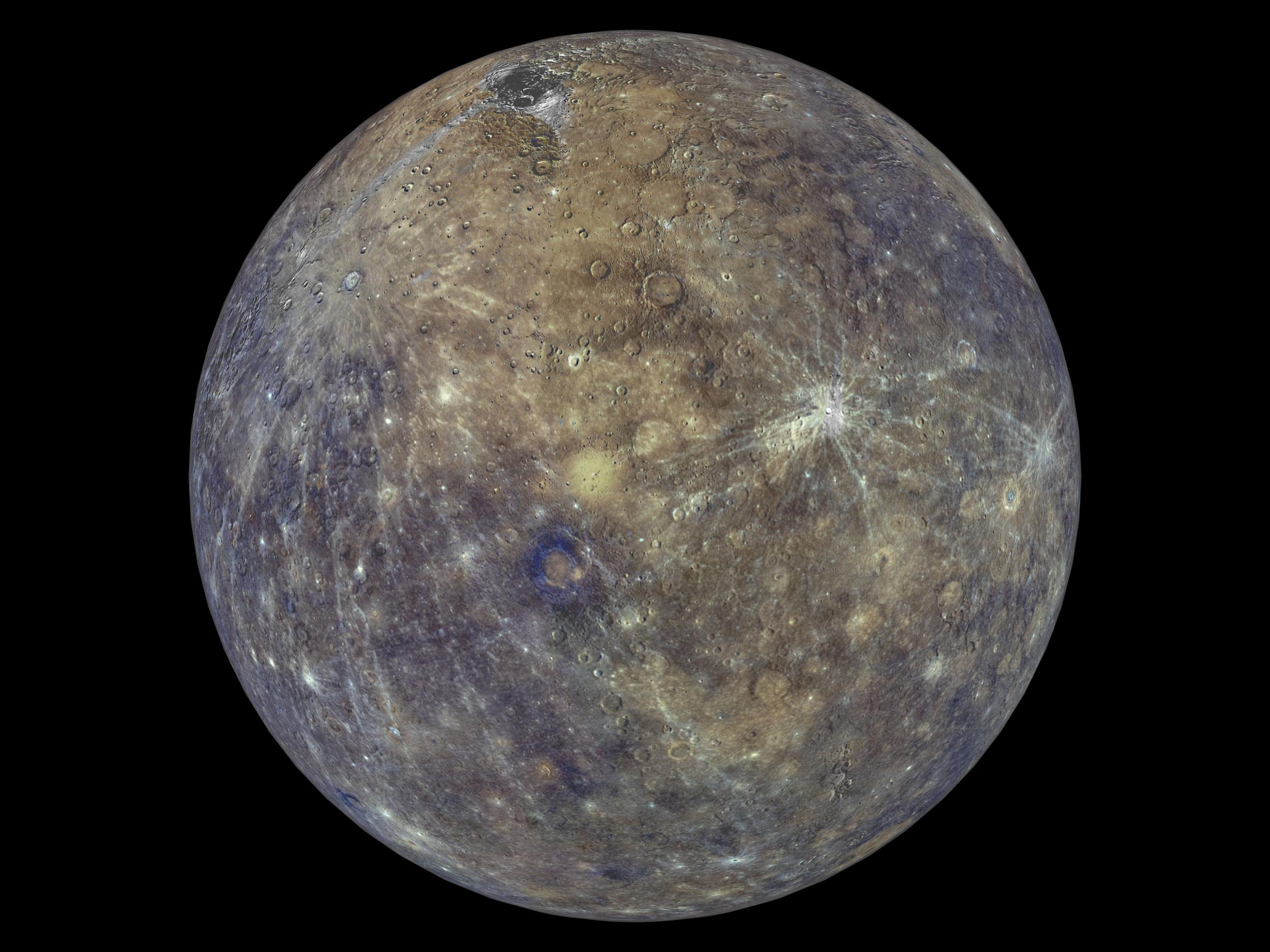

Most people – many astronomers included! – have never seen Mercury. The innermost planet, this tiny world hugs the Sun, circling it in just 88 days. So it is never far from our local star in the sky. Even Nicolaus Copernicus – the architect of our Solar System –was never able to observe the runt of the planets. It was permanently obscured by mists rising from the River Vistula in northern Poland when it came on view.

But this month is different. Weather permitting, we’ll all get a chance to see little Mercury as it crosses (”transits”) the face of the Sun. The date for your diary is 11 November.

Inevitable warnings, first. The transit takes place in the middle of the day, when the Sun’s rays – even in November – are at their most powerful. Never look directly at the Sun. And never ever use optical aid to get a close-up: it could well blind you. More advanced starwatchers may have specialist solar binoculars or telescopes. If you’re a complete beginner, you can use a small telescope or binoculars to throw an image of the Sun onto a sheet of white card.

Best of all, take yourself to one of the 30 public viewing events around the UK, where local astronomers will show you the transit in total safety and provide all the low-down. Check out the map and details here.

Transits are mini-eclipses. Only Mercury and Venus (the innermost planets) can be seen in transit; it’s fascinating to watch their tiny discs slowly cross the Sun’s face.

In the past transits were valuable scientifically for gauging the size of the Solar System. In 1789, expeditions from Europe travelled to all corners of the globe to observe a transit of Venus. By timing the progress of the planet across the Sun’s disc – and comparing it to the Earth’s motion – they were able to calculate the distance of the Earth from the Sun. This distance – the astronomical unit – is a fundamental step in determining the distances to all the other planets.

SpaceX's journey through the Solar System

Show all 6So what can we expect on 11 November? Mercury will start its transit at 12.35pm; it’s halfway across the Sun by 3.20pm; and the planet is still in transit at sunset (about 4.30pm).

Sometimes the Sun suffers a rash of dark sunspots, and it may be difficult to work out which particular blemish is Mercury. But our local star is currently at the minimum of its magnetic activity at the moment, and we don’t expect a confusing peppering of sunspots. Anyway, the hard, sharp silhouette of Mercury looks distinctly different from the fuzzy blurs of any sunspots. And at maximum transit, it will be right in the middle of the Sun’s disc.

November is the most unpredictable month, weather-speaking, so ... fingers crossed. Otherwise, put 13 November 2032 in your diary – that will be Mercury’s next encounter with the face of the Sun.

What’s up

The starry skies are rather drab this month, dominated by the giant faint constellations of Pegasus (the flying horse), princess Andromeda and Cetus, the cosmic whale. The bright stars of summer – Vega, Deneb and Altair – are slipping down to the west. In the east, the glittering Pleiades (the Seven Sisters star cluster) herald the glories of the winter sky, with the familiar shape of the mighty hunter Orion rising about 10pm.

But look low in the south-west just as the sky grows dark, and you can spot the planets having some fun. As the sky grows dark in early in November, you’ll find brilliant Venus right down on the horizon, with the second brightest planet Jupiter to its upper left, and further in the same direction the rather fainter Saturn.

As the month progresses, Venus moves towards Jupiter. We are in for a beautiful sight on 24 November, when the Evening Star passes directly below the giant of the Solar System – the two brightest planets getting up close and personal. On 28 November, look out for another stunning tableau when the crescent moon lies between Venus and Jupiter.

On the night of 17-18 November, the Earth runs into debris from Comet Tempel-Tuttle, igniting as meteors as they crash into the atmosphere. This year, though, the annual Leonid shooting stars will make a rather poor display because the sky will be lit up by moonlight.

Diary

11 November: transit of Mercury

12 November, 1.34pm: full moon

13-14 November: moon in the Hyades star cluster, near Aldebaran

16 November: moon near Castor and Pollux

17-18 November, 1.39pm: maximum of Leonid meteor shower

19 November, 9.11pm: last quarter moon near Regulus

24 November: Venus near Jupiter

26 November, 3.06pm: new moon

28 November: Mercury at greatest western elongation; crescent moon between Venus and Jupiter

29 November: crescent moon near Saturn

Philip’s 2020 Stargazing (Philip’s £6.99) by Heather Couper and Nigel Henbest reveals everything that’s going on in the sky next year

Fully illustrated, Heather and Nigel’s The Universe Explained (Firefly, £16.99) is packed with 185 of the questions that people ask about the Cosmos

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies