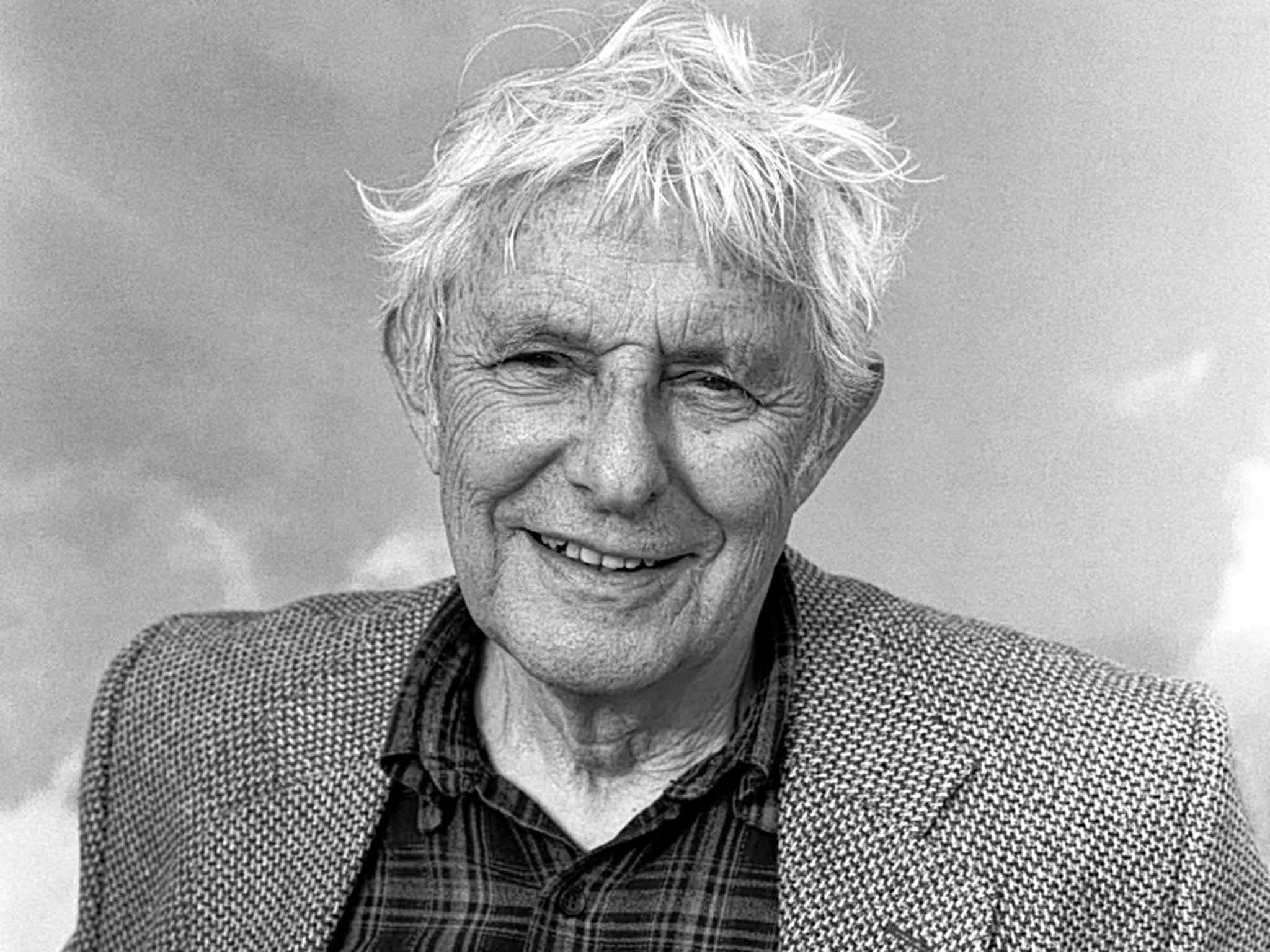

Dannie Abse: Physician and writer who combined work in a London hospital with a prominent position in British poetry

As a uniquely compelling poet in many forms, entrancing reader of his own verse, Jewish Welshman living in London, and active figure in influential poetry circles, Dannie Abse was one of the prominent British poets of his time. In his stage play Pythagoras there is a small song which Abse commentators often cite. It includes the stanza:

"And phantom rose and blood most real

Compose a hybrid style,

White coat and purple coat

Few men can reconcile."

White Coat, Purple Coat was the title of his expanded collected poems of 1989. Pythagoras's two coats thus embody Abse's dual vocations of hospital doctor and poet. Yet the play sees the purple coat as not poet's but magician's, a telling point about Abse's poetry, which he himself said was intended to work by deception – actually by masterly indirection, by pointing to a thing's detail or appendage, so as to leave the reader to infer the matter's true thrust. So the poem "Chalk" is on writers of political graffiti, and "Red Balloon" a Jewish boy tormented by peer-Christians. Hardly a new mode in art, but Abse's richness of material and skill in deploying it thereby brought him endless poetic opportunities.

Indeed, white and purple were not the only colours. Joseph's coat, the peacock and the rainbow recur compulsively in the verse, as do the spectrum's individual components. In one of his best-known poems, "Pathology of Colours", the poet finds their beauty missing in the sick or mutilated human bodies he saw in his professional life. This spread of colour symbolises exactly the range of experience which the poetry, largely autobiographical prose, and plays, over five decades has contained. The binaries are several: as his friend Daniel Hoffman once put it, British-Jewish, English-Welsh, seeker-sceptic, bourgeois-bohemian, and poet-doctor too.

Dannie Abse's childhood and home life may have nurtured this eclecticism. He was born in Cardiff in 1923. His father was a cinema manager who played the violin, while his mother spoke Hebrew, English and Welsh, and recited long tracts of poetry to the family. His elder brothers Leo (later MP for Pontypool) and Wilfred (later professional psychoanalyst) kept up, in effect, a running Marx-Freud debate during the young Dannie's teens, and his sister Huldah taught him to dance.

As youngest of all these, and being the only Jewish pupil at the formally Christian St Illtyd's College (secondary school) in Cardiff, Dannie could receive impressions as well as give them off. It led to at least the first part of his self-declared life-motto: "be visited, expect nothing, and endure". Over it all hung the War, as the rest of the motto suggests, with its final exposure of Belsen and Auschwitz. This was the black in Abse's colour-spectrum; its shadow hangs over his poetry for decades to come, although it softened somewhat in the final books.

After St Illtyd's he studied at the Welsh School of Medicine in Cardiff, followed by King's College London and Westminster Hospital, the latter two institutions both attended earlier by brother Wilfred, again attesting to the young man's impressionable situation. Not surprising, then, that his precocious early poetry was full of influences: the Bible, Hardy, Rilke, but TS Eliot too, who encouraged the young poet and whose phrases echo through Abse's texts and titles alike.

Dylan Thomas was the major overt force, as for so many poets at the time, Welsh and English, yet in Abse's "Elegy for Dylan Thomas" one even hears the deadpan suavity of Auden's elegies for Freud and Yeats. However, Abse did take aboard the late-romantic mode in full throttle for a period – evinced strongly, too, in the prose of his still-selling autobiographical novel Ash On A Young Man's Sleeve (1954) – and bringing short prominence as a "maverick".

This was his response to Robert Conquest's Movement anthology New Lines of 1956, with its key and much-cited line, "A neutral tone is nowadays preferred". Not by Abse's anthology (Mavericks, 1957), jointly edited with Howard Sergeant, which promoted unLarkinesque poets like Michael Hamburger, Jon Silkin, John Heath-Stubbs and Abse himself. They relished language's sounds, its palpable jostling references, and the dreamy, narrated poems and fables it could therefore generate.

Meanwhile Abse's own collections were appearing. Later he more or less disowned the first, After Every Green Thing (1948), for its wordy fulsomeness. But it was a feather in his cap to have it accepted when he was only 23, by Hutchinson, his loyal publisher for the next half-century. Five more collections followed, including Poems, Golders Green (1962), A Small Desperation (1968) and Funland and Other Poems (1973) before the first Collected Poems appeared in 1977. The collections became quieter; old age looms, even Auschwitz drops away a little, the meditations are more inward.

Abse published prolifically in other genres: two novels, a two-part autobiography A Poet in the Family (1974) and his numerous plays, half a dozen of which were staged at the Questors Theatre in Ealing, the Edinburgh Festival, the London Old Vic, the Birmingham Repertory Theatre and elsewhere. The plays give rein to Abse's attested conversational urge – as in the poetry, too – but also to his many roles, real or adopted: maverick, magician, joker, victim, friend and visionary.

Yet he is best known for his poetry, which seems likely to be remembered the most of his work. Gradually his multifarious experiences, images and perceptions, while always clear in individual profile, found the uniting voice he so keenly sought, and the memorable poems came.

Among so many of note, one thinks of "Pathology of Colours", "Olfactory Pursuits" "Return to Cardiff", "A Night Out", "Not Adlestrop", "In The Theatre" and "Last Words", to his wife Joan, the adult-life companion who cannot be forgotten in any Abse context. He wrote six poems a year; in retirement, once, up to nine; "a record", he said.

He didn't care for the 1960s revolution to loosely slung forms and spurious-pop language. Just occasionally he could be too much the self-publicist, or tight-lipped about perceived rivals, but his generous spirit normally swamped such reactions. He once found himself at a Hay-on-Wye festival reading on stage alone (bar the chairperson) with Enoch Powell. Combining good humour with pointedness, Dannie read a poem about German prisoners of war arriving by train at Bridgend and mistaking the uniformed station master for a senior British Army officer. He would never have applied Whitman's line to himself, so we can do it for him: "I am large, I contain multitudes."

As a hospital doctor in London for over 40 years he saw daily the life-casualties, medicine and surgery on which, along with Judaism's afflictions, a major side of his poetry centred. It was balanced by his unforgettably cheering roars of laughter – in poetry and out of it – at gentler human vagaries elsewhere. In the Referendum period of the 1970s his attention turned back to Wales, where he had always returned regularly to watch his beloved Cardiff City, through thin and mostly thin.

He began encouraging Wales's younger poets, who he saw as being sold short next to the high profile of their counterparts in Ireland. Whether as editor, anthologist, or award panellist he never crudely pushed their causes; rather he would quietly but effectively ensure that their names and works were not overlooked. The strong current list of younger Welsh poets like Deryn Rees-Jones, Kate Thomas, Paul Henry and Owen Sheers may be in his debt to that extent.

His and Joan's two homes, with the book-lined living room and conservatory in North London and the cool, lucid, near-Mediterranean cottage in south Wales at Ogmore-by-Sea (he enjoyed the thought that he had been conceived there) were perpetual welcome-houses to countless poets and other visitors. He was immensely popular in the poetry world, and had a wide following in America. He was a Doctor of Literature of the University of Wales, Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and Fellow of the Welsh Academy. He was President of the Poetry Society of Great Britain from 1979-92.

In June 2005 Joan, Dannie's wife of over 50 years, was killed in a car crash in south Wales in which the poet was also involved. The sense of grief through the literary communities of London and Wales was palpable. His collection Running Late was published in 2006, and The Presence (2007), a memoir of the year following his wife's death, won the 2008 Wales Book of the Year award.

Daniel Abse, poet and physician: born 22 September 1923; married 1951 Joan Mercer (died 2005; two daughters, one son); died 28 September 2014.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies