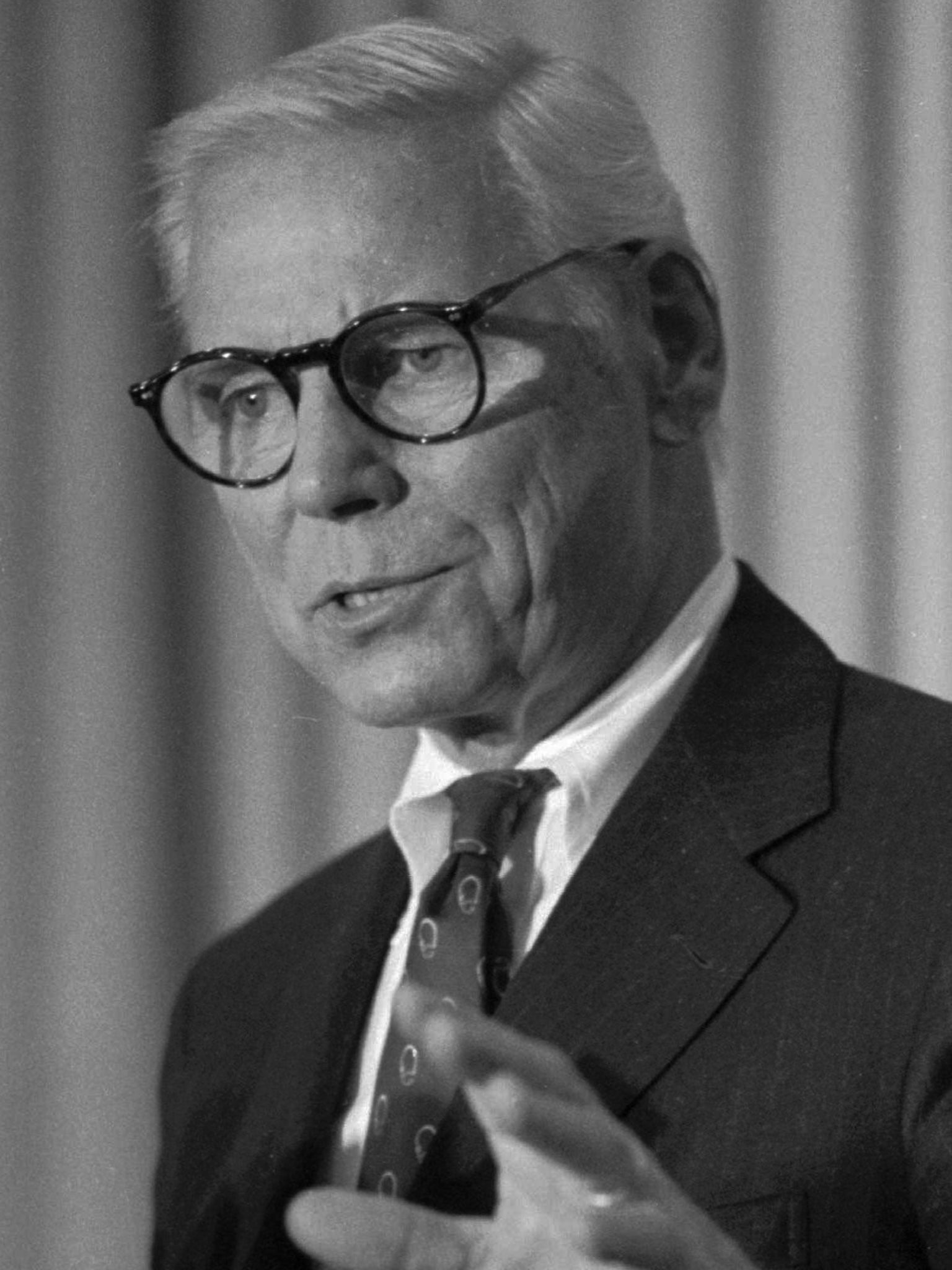

Warren Anderson: Chief executive of Union Carbide at the time of the catastrophic gas leak at their plant in Bhopal, India

On 3 December 1984 an explosion at the Union Carbide chemical factory in Bhopal, India caused the worst industrial disaster in history.

More than 2,200 people were killed following the escape of the toxic gas methyl isocyanate from tanks at the factory. In the 30 years since the tragedy, the death toll has risen to 20,000, with more than half a million people injured and still suffering the effects of gas poisoning.

W M Anderson, the chief executive of Union Carbide, whose death in September has just been announced, visited the plant four days after the accident, in what was then seen as a timely reaction from the company. However, after being arrested by Indian police on the spot and paying bail, he was released and never returned to the country. He remained a fugitive from the Indian legal system, resisting all efforts to bring him to face trial for the company’s actions.

Interviewed in the US five months after the disaster – his only comments to the media since the disaster – he said, “You wake up in the morning thinking, ‘Can it have occurred?’ And then you know it has and you know it’s something you’re going to have to struggle with for a long time.”

Since the disaster there have been many attempts by the Indian judicial system to bring those alleged as responsible to face the court. Union Carbide paid $470m to the Indian government in 1989 to settle civil litigation – but US adminstrations over the past three decades have not co-operated in helping India to bring Anderson to justice on criminal charges.

In February 1992, the chief judicial magistrate of Bhopal declared him a fugitive from justice for failing to appear at court on charges of culpable homicide. An arrest warrant was issued in July 2009, but the company responded publicly by claiming that Anderson could not have anticipated the gas leak. A company spokesman said at the time, “The release had terrible consequences, but it makes no sense to continue to attempt to criminalise a tragedy that no one could have foreseen.”

The Indian Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) subsequently made a request for Anderson’s extradition in March 2011. “Considering the entire facts in its holistic perspective and sentiments of the disaster-hit people, I deem it appropriate and in the interest of justice that he be extradited,” chief metropolitan magistrate Vinod Yadav said. However, in April this year it was reported that the US had still not taken a decision on the request, more than three years after, citing a lack of evidence.

In June 2010 a Bhopal court sentenced seven local Union Carbide staff to two years in jail and a fine of 100,000 rupees (then £1400) on charges of “death by negligence” and “culpable homicide not amounting to murder”. While 85-year-old Keshub Mahindra, the chairman of Union Carbide India, was convicted and jailed, Anderson was not among those sentenced.

“The message of the verdict is that the corporations can come, kill and release toxic gases and nothing will happen to them,” said Rachna Dhingra, a campaigner for the International Campaign for Justice in Bhopal. Rashida Bee, president of the Bhopal Gas Women’s Workers group, commented at the time that “justice will be done in Bhopal only if individuals and corporations responsible are punished in an exemplary manner.”

The precise cause of the explosion has not so far been established. What is clear is that various safety systems, which could have prevented or slowed the release of the gas, were out of action. In particular, a coolant system had been deactivated in order to save on energy costs. Over the course of an hour on the day of the disaster, some 30 tonnes of methyl isocyanate escaped from the plant into the atmosphere in the densely populated city of Bhopal. Union Carbide has, since 2001, been a wholly-owned subsidiary of Dow Chemical. Yet today the plant is derelict, has still not been cleaned up by its new owner and remains a toxic hazard.

Anderson was born in 1921 in Brooklyn, New York, the son of Swedish immigrants, who named him after the then president Warren G Harding. As a youngster he delivered newspapers and helped his father, a carpenter, to install floors. He won sports and academic scholarships to Colgate University, New York and graduated with a degree in chemistry in 1942. He was drafted into the US Navy and trained as a fighter pilot, but did not see active service during the Second World War.

He had joined Union Carbide as a salesman and had risen to the position of chief executive in 1982. On retiring in 1986, Anderson spent his time between homes in Bridgehampton, New York and Vero Beach, Florida, where he died.

Kate Allen, UK director of Amnesty International, told The Independent, “Any death brings sadness, but Warren Anderson’s calls to mind the death and suffering of so many innocent people and their quest for justice. Mr Anderson’s death comes just a month ahead of the 30-year anniversary of the Bhopal disaster, which caused 20,000 deaths and even now continues to poison and ruin thousands of lives. Mr Anderson’s successors at Dow Chemical should heed Bhopal’s call for justice.”

WM Anderson (Warren M Anderson), businessman: born Brooklyn, New York 29 November 1921; married Lillian Anderson; died Florida 29 September 2014.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies