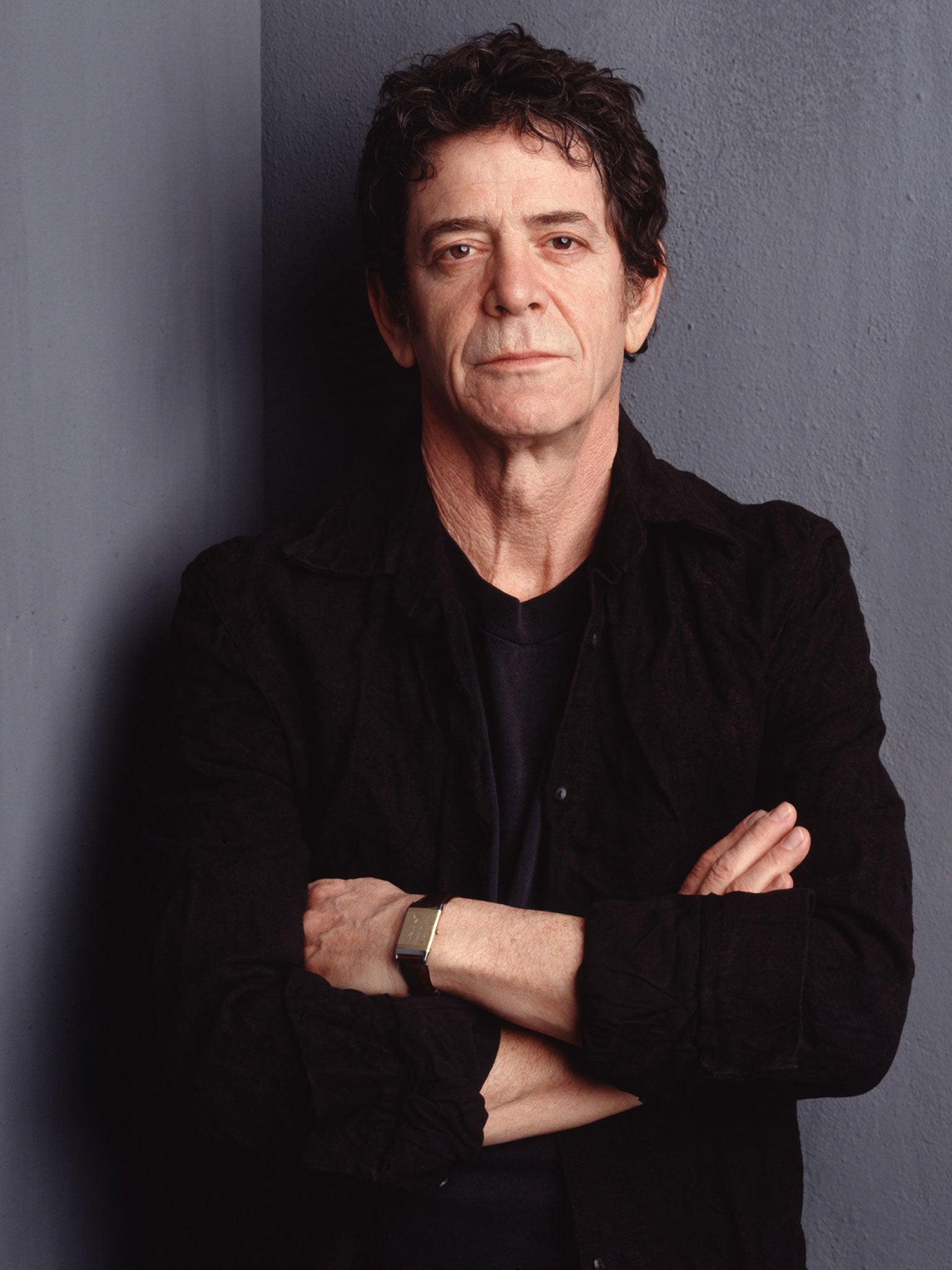

Lou Reed obituary: Singer and founder of the Velvet Underground

'I wish you could approach rock'n'roll with the same intensity as a great novel'

While Bob Dylan has sold many more records, Lou Reed helped shape the past four decades of rock and pop just as much, if not more. A singer with a half-spoken, deadpan delivery and a songwriter with a novelist's eye for detail, in the late Sixties he captured the demi-monde and the noir underbelly of his native New York as the leader of the Velvet Underground. On their seminal debut, The Velvet Underground & Nico, songs such as “Heroin” and “Venus in Furs”, about drug abuse and sado-masochism, touched darker subject matter than the Rolling Stones or even the Doors had tackled by then. Despite being packaged in the peelable “banana” cover designed by their then mentor Andy Warhol, it didn't make much of an impact when it was released in the spring of 1967. It simply didn't belong in the Flower Power era and the “summer of love” that soon dominated popular culture and the youth agenda. Yet, as Brian Eno later observed, every one of the 30,000 people who bought a copy of The Velvet Underground & Nico between 1967 and 1972 started a band, setting off an influential chain of events that resonated through glam, punk, post-punk, industrial and electronic music, the New Romantics, indie, grunge and beyond.

Much of this was facilitated by David Bowie who, in concert and for BBC radio, covered “I'm Waiting for the Man” from the band's debut album, and “White Light/White Heat”, the title track of the second. On his 1971 album Hunky Dory, Bowie penned an ode to Andy Warhol and also paid homage to the Velvets with “Queen Bitch”. Bowie and his guitarist, Mick Ronson, went on to co-produce Reed's second solo album, Transformer, in 1972. It contained “Walk on the Wild Side”, an unlikely hit single with its memorable “doo-doo-doo-doo” chrorus and a risqué lyric about “giving head” that somehow slipped past the BBC censors when Johnnie Walker made it his record of the week on Radio 1 in the spring of 1973.

“That means my rent has been paid all these many years from you, Johnnie Walker,” Reed said when talking to the disc jockey recently. “You're the one who made it a hit. Because, in the United States, it was nothing but a long bleep. I thought it was hilarious. I couldn't believe it – when you have the movies that you have, the books that you have, when you have Naked Lunch, when you have Last Exit to Brooklyn – that something as completely innocent as ”Walk on the Wild Side“ actually got bleeped by these people. 'I've got a BA in English,' I said. 'This is not Ulysses. My God!'”

Transformer went on to spend half a year on the UK album charts and introduced three other mainstays of the Reed repertoire: the rocking opener “Vicious”, a staple of his concerts and many live albums, and a brace of much-covered gorgeous ballads with a sense of longing, “Satellite of Love” and the universally popular “Perfect Day”. In a BBC campaign featuring Reed and a host of other vocalists including Bono, Bowie and Suede frontman Brett Anderson, another Reed disciple, a new version of “Perfect Day” topped the British charts for three weeks at the end of 1997, the proceeds going to Children in Need. It confirmed Reed's standing as a consumate songwriter, something longstanding connoisseurs of his oeuvre already knew since they were familiar with the 1975 mellow masterpiece Coney Island Baby or Magic and Loss, the 1992 concept album inspired by the death of a friend, the songwriter Doc Pomus.

Able to convey beauty, sadness and vulnerability, as he did with the Velvets on “Sunday Morning”, “Pale Blue Eyes” and “Who Loves the Sun”, he could also be mean, nasty and provocative, as in his bleak rock opera Berlin, the 1973 follow-up to Transformer that halted his mainstream career in the Seventies. The critical drubbing Berlin received in the US on its release soured his relationship with music journalists more or less permanently, though the album is now acknowledged as one of his best, and was successsfully performed in its entirety with a choir and orchestra in 2007. Equally, the feedback feast that was 1975's double set Metal Machine Music, perceived at the time to be a contractual fulfillment release or a joke gone too far is now considered a forerunner of noise rock and has been played by classical ensembles. In 2008 Reed formed the Metal Machine Trio to further mine that avant-garde seam. “Music's never loud enough. You should stick your head in a speaker. Louder, louder, louder,” he was fond of saying.

Forever described as the godfather of punk, alongside Iggy Pop, another artist whose career was furthered by Bowie, Reed described his basic approach to guitar playing: “One chord is fine. Two chords are pushing it. Three chords and you're into jazz.” He remained fond of the doo-wop of his youth: Dion DiMucci, frontman of Dion and the Belmonts guested on his album New York, released in 1989. This was one of Reed's most powerful collection of songs and included the paean to Aids victims “Halloween Parade” and the swaggering “Dirty Blvd”. “This is what eight years of Reagan does to you,” he said then. “I knew I wasn't the only one feeling these things. Especially in New York. It's the strongest thing I've ever done.”

Reed was a believer in the power of rock'n'roll as an art form, as he demonstrated with The Raven, his 2003 song cycle based on the short stories and poems of Edgar Allan Poe, and Lulu, his 2011 collaboration with rock giants Metallica adapted from two plays by Frank Wedekind. “Party music is great, dance music is great,” Reed remarked. “But I wish you could approach rock'n'roll with the same intensity as a great novel.”

Born Lewis Allan Reed in 1942, he was the son of an accountant and a stay-at-home mother who worried about his mood swings and lack of respect for teachers and rabbis, and his latent bisexuality. In his mid-teens, he underwent weeks of electroshock therapy, and later wrote about the experience in “Kill Your Sons”, on his 1974 studio album Sally Can't Dance.

“They put the thing down your throat so you don't swallow your tongue, and they put electrodes on your head,” he said in 1996. “That's what was recommended in Rockland County then to discourage homosexual feelings. The effect is that you lose your memory and you become a vegetable. You can't read a book because you get to page 17 and have to go right back to page one again.”

He started playing guitar while listening to rock and roll and rhythm and blues on the radio and joined various high school bands. In 1958, he made his first recording, “Leave Her for Me'” with a doo-wop group called the Jades. Two years later, he began attending Syracuse University where he studied journalism and creative writing and hosted a late-night programme on the campus radio station. There, he studied under and drew inspiration from Delmore Schwartz, the poet and short- story writer to whom he would dedicate “European Son” on The Velvet Underground & Nico.

After graduating in 1964, he worked as an in-house songwriter for Pickwick Records, where he composed and cut a novelty dance song entitled “The Ostrich” which was credited to The Primitives and became a minor hit in New York. The unusual guitar tuning and drone effect Reed employed on the recording attracted the attention of John Cale, a Welsh musician who had moved to New York to study music and who was using similar techniques while playing viola with avant-garde composer La Monte Young.

Reed and Cale teamed up and recruited guitarist Sterling Morrison and drummer Maureen Tucker to form the Velvet Underground, named after a pulp paperback with a sado-masochistic cover, written by Michael Leigh. As Reed recalled, they lived “in a $30-a-month apartment. We really didn't have any money. We used to eat oatmeal all day and all night and give blood, among other things.”

Their fortunes improved when they came into Warhol's orbit after he saw them at the Café Bizarre in Greenwich Village at the end of 1965 and incorporated them into his Exploding Plastic Inevitable multi-media events. “Andy would show his movies on us. We wore black so you could see the movie. But we were all wearing black anyway,” he recalled. At first, Reed was reluctant to have the German model and singer Nico join them, but he relented and composed several songs that suited her, including “I'll Be Your Mirror”, based on a remark she had made, and “Femme Fatale” and “All Tomorrow's Parties”, both inspired by the Warhol milieu they had been absorbed into.

“Andy Warhol told me that what we were doing with the music was the same thing he was doing with painting and movies and writing – i.e. not kidding around,” said Reed. “Nobody in music was doing anything that even approximated the real thing, except us. We were doing a specific thing that was very, very real. It wasn't slick or a lie.”

Though Warhol was credited as producer on the Velvets' debut, his involvement in the studio was minimal, but his aura enabled Reed to take a stand and avoid watering down the subject matter of “I'm Waiting for the Man”, “Run Run Run” and “Heroin”. “Andy made a point of trying to make sure that on our first album the language remained intact. Andy was interested in shocking, in giving people a jolt and not letting them talk us into making compromises. He said, 'Oh, you've got to make sure you leave the dirty words in.' He was adamant about that,” remembered Reed. “He didn't want it to be cleaned up and, because he was there, it wasn't. And, as a consequence of that, we always knew what it was like to have your way.”

The Velvet Underground & Nico reached a lowly 171 in the US album charts, but has grown so much in stature that its 45th anniversary super deluxe edition issued a year ago comprised six CDs. By the time the Velvets recorded their much darker second album in September 1967, they had parted company with Nico and Warhol. Cale was driven out the following year and Reed recruited Doug Yule for 1969's The Velvet Underground and 1970's Loaded, for which he first recorded the epochal “Sweet Jane” and another classic, “Rock and Roll”.

Reed left the group in August 1970. For a while, he worked as a typist at his father's firm, but in 1971, he came to London to record his eponymous solo debut on which he revisited several latter-day Velvet songs. In January 1972, he reunited with Cale and Nico at Le Bataclan in Paris, for a concert filmed and broadcast by French TV which helped pave the way for his reemergence with Bowie.

With the arrival of punk in the mid-Seventies, Reed, then living with a transgender woman called Rachel, and still dabbling with drugs, was in typically contrary mood. “I'm too literate to be into punk rock,” he said at the time, though 1978's Street Hassle certainly fitted punk. Its title track was later covered by Simple Minds, one of many acts he influenced, along with the Psychedelic Furs, The Waterboys and Berlin, all named after a Reed lyric or album. In 1987, he made the UK charts duetting with Sam Moore on a dynamic version of “Soul Man” featured in the eponymous comedy film about racial transformation.

Following Warhol's death, Reed and Cale teamed up again to pay homage to the artist and former mentor on the 1990 album Songs for Drella. Three years later, they joined Morrison and Tucker in a Velvet Underground reunion for European dates and the Live MCMXCIII album. The band didn't make it to the US, though they were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1996. By then, Reed had found a kindred spirit in the musician and performance artist Laurie Anderson. They appeared on each other's albums and married in 2008. Earlier this year, Reed underwent a liver transplant. He died of liver disease at his home on Long Island.

“Rock'n'roll is so great, people should start dying for it,” he said in 1996. “After all, all the great blues singers did die. But life is getting better now. I don't want to die, do I?”

Lewis Allan Reed, songwriter, guitarist:born New York 2 March 1942; married 1973 Bettye Kronstadt (marriage dissolved); married 1980 Sylvia Morales (marriage dissolved); married 2008 Laurie Anderson; died New York 27 October 2013

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies