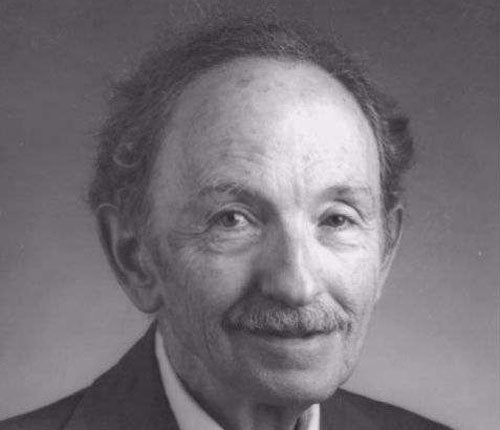

Jack Good: Cryptographer whose work with Alan Turing at Bletchley Park was crucial to the War effort

In the 1960s Jack Good, known in the United States as an academic working in statistics and mathematics, used to drive around the campus of Virginia Tech University in a car which sported the personalised number plate 007 IJG. It was his oblique way of referring to what for decades he could not speak about – his important wartime role as a codebreaker at Bletchley Park, where he and colleagues did work which is credited with shortening the war.

He worked closely with Alan Turing, Bletchley's presiding genius, and other near-legendary figures such as Max Newman and Donald Michie. They used a mixture of rudimentary computers and sheer brainpower to break German codes and give Allied commanders huge tactical advantages.

Good was 24 when he arrived at Bletchley, initially ruffling feathers by sleeping during a night shift but quickly redeeming himself by pointing out a procedure for one machine which had not occurred to his more experienced colleagues. As he later explained it, in the all-but-impenetrable language of the statistical cryptanalyst, "I had an extremely simple idea that cut the work by about 50 per cent. It was the replacement of scores such as 3.6 decibans (stored as 36 centibans) by 7 half-decibans. Nearly all the entries, of which there were a few thousand, could then be expressed by a single digit." [A ban is a logarithmic unit that measures information]. This was one of Good's most important insights, but it was just one of thousands of ideas, notions, thoughts and speculations he came up with in his long career. A prolific author with many books and almost a thousand papers to his credit, his published writings ran to about two million words in which he ranged over statistics, physics, mathematics and philosophy. One reviewer summed up his record: "For more than 30 years I.J. Good has been prodding, stimulating, criticizing, enlightening, surprising and amusing colleagues with his dazzling insights into the dark mysteries of probability and scientific inference."

His first insight, and one of his most remarkable, came when he was nine years old. Confined to bed with diphtheria, he mulled over the square root of 2 and came up with a new understanding of its mathematical subtleties. Seventy years later Good said: "I'm proud of that, even now, because if there was any single instance in my life that shows that I had a little bit of mathematical genius, I think that was it. At the age of nine, it wasn't bad to make a discovery that was described as one of the greatest achievements of the ancient Greek mathematicians."

Good, whose original name was Isidore Jacob Gudak, was the son of a Russian mother and Polish father who met in London. His father was first a watchmaker and later a prominent antique-jewellery dealer near the British Museum. At Haberdashers' Aske's School in Hampstead Good was not an all-rounder: "History I did not enjoy," he recalled. "I would always fall asleep during history lessons."

But he was recognised as a maths prodigy and went on to win a scholarship to Jesus College, Cambridge, where he took a first-class degree and a PhD in mathematics. His aptitude for maths – and for chess – drew him to the attention of Hugh Alexander, a chess champion who was also a senior figure at Bletchley. Recruited by Alexander in 1941, Good spent the rest of the war there, immersed in profound statistical thought and in designing and operating primitive computers. He was one of the few who could keep up with Turing's sometimes eccentric brilliance.

Their efforts paid huge dividends and almost certainly shortened the war. He once mused: "There must have been occasions when we read a message from Hitler to his generals before the general read it." Good once summed up: "The feeling that we were helping substantially, and perhaps critically, to save much of the world – including Germany – from heinous tyranny was a hard act to follow."

Good and the others always acknowledged the primacy of Turing as a thinker and problem solver. "I won't say that what Turing did made us win the war," he once observed. "But I daresay we might have lost it without him."

In addition to working long hours on breaking Nazi codes, Turing, Good and others found time to indulge in futurology. They conjectured that computers might become smaller – they were then the size of a room – and that they might play chess. They pondered on artificial intelligence.

After the war he joined Turing and Newman at Manchester University, where they achieved an important advance by creating the first computer controlled by an internally stored programme. But after a few years he returned to the secret world, spending a decade at Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), Bletchley's peacetime successor. A variety of posts followed before he spent three years teaching at Oxford.

"I found Oxford a bit stiff, actually," he recalled. "It was somewhat taboo to talk shop at dinner time. One could talk about cricket, and things like that. I wasn't sorry to leave to come to America."

His 1967 move across the Atlantic took him to Virginia Tech, which he found much more congenial and where he spent decades. He insisted however: "I always thought of myself as British."

He attracted various honours and awards, and doubtless would have accumulated more had his work at Bletchley and GCHQ not remained top secret. He was once described as "the overlooked father of computation."

He was consulted by Stanley Kubrick when the producer was researching his classic film 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). In the movie a spaceship's on-board computer develops a mind of its own, with lethal consequences: Good largely viewed computers as a marvellous tool, but occasionally suspected that they might ultimately become dangerous.

For years Good stuck to his thesis that computers might have personality traits, arguing: "My computer tells lies and often forces me to shut down improperly. Such behaviour in a human would be called neurotic."

He remained to the end as fascinated with numbers as he had been at the age of nine. He said of reaching Virginia: "I arrived in the seventh hour of the seventh day of the seventh month of year seven of the seventh decade, and I was put in apartment 7 of block 7, all by chance. I seem to have had more than my fair share of coincidences. I have an idea that God provides more coincidences the more one doubts Her existence, thereby providing one with evidence without forcing one to believe. When I believe that theory, the coincidences will presumably stop."

David McKittrick

Isidore Jacob Gudak (Irving John Good), mathematician and cryptographer: born London 9 December 1916; died Radford, Virginia 5 April 2009.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies