Review: Book recalls '64 coast-to-coast adventure in a bus

Author Ken Kesey, flush with cash from the publication of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” filled an aging, broken-down school bus with friends in 1964 and led them on a drug-fueled drive across America, later recounted in vivid detail in Tom Wolfe’s 1968 best-seller, “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.”

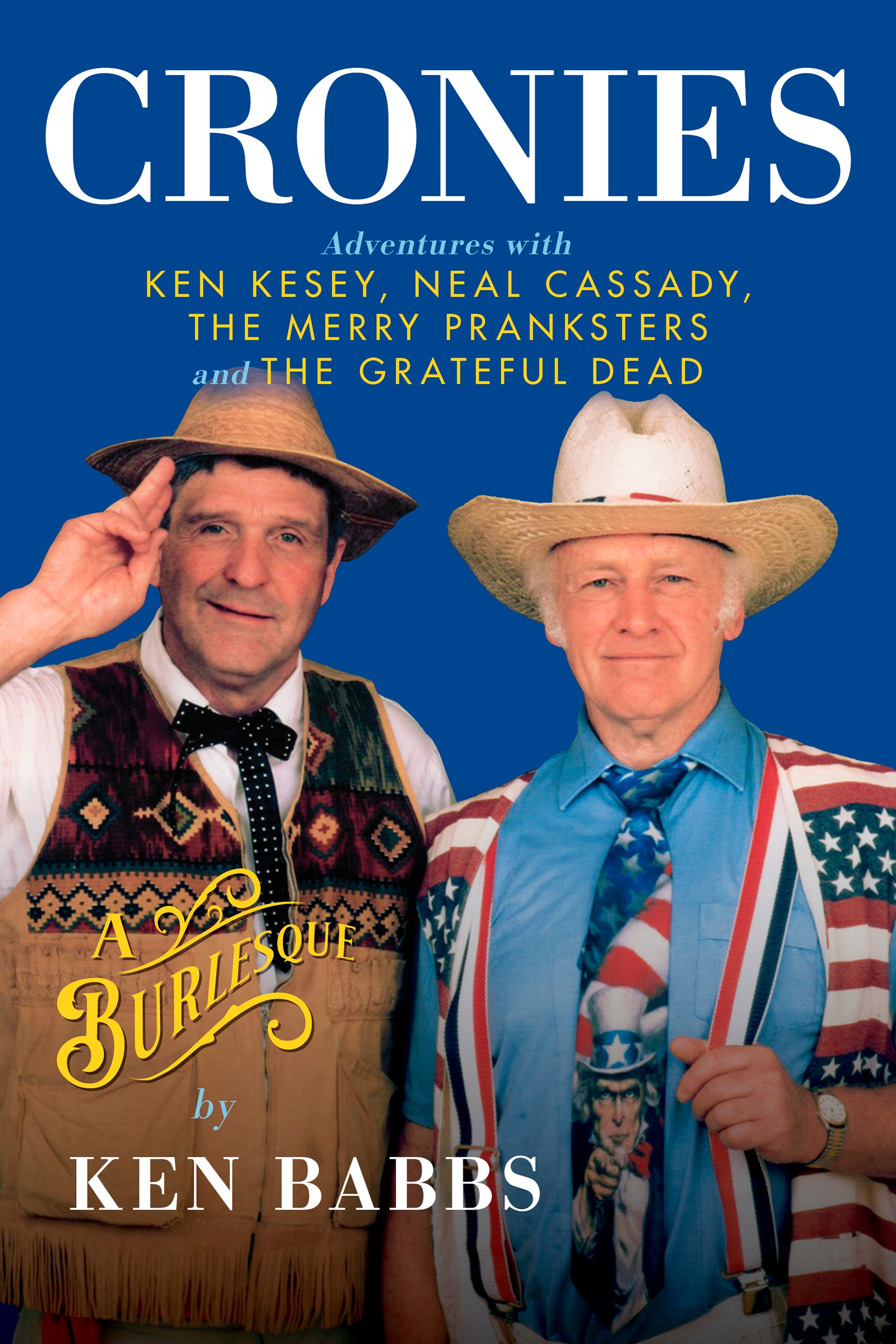

“Cronies” by Ken Babbs (Tsunami Press)

Author Ken Kesey, flush with cash from the publication of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” filled an aging, broken-down school bus with friends in 1964 and led them on a drug-fueled drive across America later recounted in vivid detail in Tom Wolfe’s 1968 best-seller, “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.”

More than a half-century later, Kesey’s longtime consigliere has weighed in with his own account of that memorable journey and numerous others.

“Cronies” is not Ken Babbs’ first book and perhaps not his best. But it will likely serve as a must-read for aging hippies, admirers of Kesey and anyone who wondered whatever happened to that group calling itself the Merry Pranksters, whose members gave each other nicknames like Stark Naked, Anonymous Hassler, the Cadaverous Cowboy and Zonker.

Age, illness and death have caught up with some, including Kesey, who died of cancer in 2001. A few others have grown old gracefully and in some cases surprisingly successfully. All are remembered quite fondly.

Babbs, now 83, was second-in-command to Kesey during that coast-to-coast adventure in a bus named Further that was painted top-to-bottom in psychedelic colors and filled with copious amounts of marijuana and LSD

Traveling through the South, Further was sometimes mistaken, Babbs writes, for a bus carrying young people known as Freedom Riders, who risked their lives to register Black voters. Alarmed Southerners often called the local police, he says, and one cop advised the Pranksters to fly a Confederate flag for their own protection. Instead, they unveiled a banner proclaiming, “A Vote For Barry is a Vote For Fun,” a tongue-in-cheek endorsement of Republican Sen. Barry Goldwater who was running for president that year.

He also confirms Wolfe’s description of driver Neal Cassady as a maniac behind the wheel who terrified everyone aboard with his high-speed maneuvers on narrow mountain roads as he kept up a nonstop patter over a loudspeaker on whatever topic came to mind.

Cassady, the Pranksters’ most tragic figure, died in Mexico three years after the bus trip, having been found barely alive on railroad tracks outside the town of San Miguel de Allende. He had taken a bet that he could run from one town to another on a frigid winter night while counting the number of railroad ties. His last words, Babbs says, included the number 64,968.

Wolfe’s book largely concludes with Kesey’s return to California after the bus trip, followed by a series of “Acid Tests” he and Babbs organized in which the Grateful Dead would perform for people high on LSD.

Babbs’ book, like the bus, takes the adventure further, and the result is that some of the freshest and most amusing stories are found in its second half.

Anonymous, the 15-year-old runaway who jumped aboard the bus in Canada and wouldn’t get off was eventually returned to her family and, as an adult, moved to Oregon to be near Kesey and his wife, Faye, who had befriended her. Although Babbs alters her real name slightly, it’s not hard to confirm she really is living in a small Northern California town now and has made little effort to hide her past.

Babbs, who lives in Oregon with his wife, a retired English teacher, goes into little detail about himself, other than to note he was a Marine Corps helicopter pilot during the early years of the Vietnam War, a fact he says defused several tense situations between police and Pranksters. He met Kesey in a graduate writing seminar at Stanford University.

He makes little mention of his own novel, “Who Shot the Water Buffalo,” based on his Vietnam War experiences, or the half-dozen slim literary volumes called “Spit in the Ocean” that he co-edited with Kesey.

In the end, this book is not so much a memoir as an affectionate remembrance of years spent raising hell with his best friend and taking others along for the ride.

As he quotes Kesey, “I live, and we all live, to breathe our own special note into this world.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.