Peace at last for Turkey's enemy within

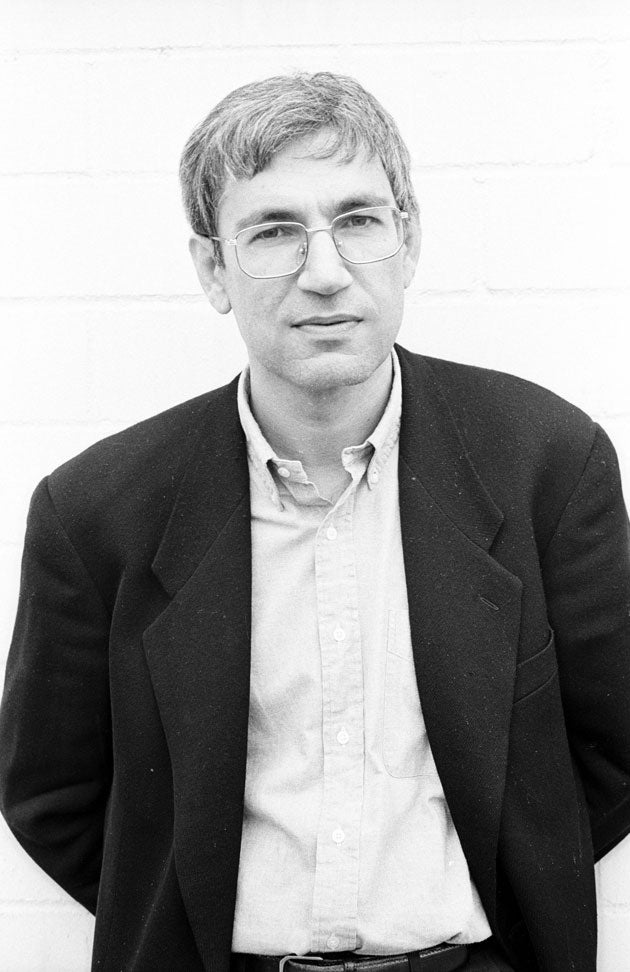

His books highlight the contradictions at the heart of Turkey. Orhan Pamuk, who has turned 60, talks to Shaun Walker

The view from the balcony of Orhan Pamuk's apartment in the hilly Istanbul district of Cihangir is almost absurd in its aptness. The minarets of the Cihangir Mosque are in close enough proximity that the muezzin's amplified call to prayer renders all conversation impossible; across the Golden Horn stands Topkapi Palace, seat of the Ottoman Sultans; further away still are the high-rise towers and business centres that drive the new Turkish economy. The view pans across the Bosphorus from the European side of Istanbul, with its tourist sights and expat-heavy districts across to the Asian side, Anatolia. Taken together, it is a neat empirical manifestation of the philosophical, cultural and geopolitical dilemmas that Turkey's best-known writer explores in his novels.

Pamuk, who turned 60 earlier this summer, has been writing books about Istanbul for three decades, and was honoured in 2006 with the Nobel Prize for Literature. Istanbul has a competitive claim to be one of the world's greatest cities, and the prominence of Pamuk as its most prescient contemporary chronicler is undisputed. This status has been further boosted in recent months with the opening of a museum, The Museum of Innocence, which is designed as the counterpart to his most recent novel, of the same name, which came out in 2009. "It was conceived together, I planned it together – I wrote the book thinking of the museum and I made the museum thinking of the novel," says Pamuk, sitting out on his balcony in the hot August sun. Before even beginning work on the novel, in 1998, he bought a house in the down-at-heel Cukurcuma district, and made it the location where one of the novel's protagonists, Fusun, would live.

The book and museum are a detailed evocation of the 1970s and 80s in Istanbul, and Pamuk spent years scouring the flea markets of the area looking for objects that would fit into his novel. "First I would find an object which I would think is suitable for my characters and stories, then write about it, and I ended up with a house full of thousands of objects," he says. Simultaneously he worked with architects on a project to turn the building into a museum to house the objects, which finally opened its doors earlier this year. The Museum of Innocence charts the obsession of Kemal, a well-to-do young man from the smart Istanbul suburb of Nisantasi, with a young cousin, Fusun, from a less wealthy side of the family. His obsessive love, which verges on creepy infatuation, leads to his emotional destruction, and he hoards objects with connections to Fusun with the intention of building her a shrine – the museum.

Given the painstaking attention to detail that Pamuk has put into the beautifully curated museum, there is a natural impulse to wonder how much the author is drawing a self-portrait. "Everyone asks me, especially women readers, 'Oh, Mr Pamuk, are you Kemal?'" he says. "No, I'm not, I'm not as obsessive as him, and I was never infatuated with love like this. But where I identify with him more is not in terms of my infatuations, but because I too fell out of my class. I'm not in touch with the bourgeois class in which I grew up, just like Kemal. Him because they made fun of him falling in love, and me because of politics and literature, which those people never cared much for."

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies