I Am The Wind, Young Vic, London<br/>Little Eyolf, Jermyn Street, London<br/>The City Madam, Swan, Stratford

One Norwegian's minimalism for half-wits, Ibsen taken too far, and a satirical 17th-century romp

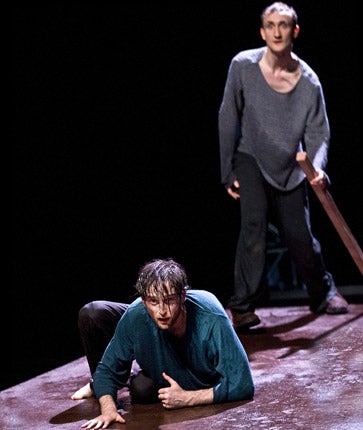

He is talking, meta-phorically, about his depression. "I just lie there/ at the bottom of the sea/ Heavy/ Motionless," says the disconsolate misanthrope, aka The One, played by a morbidly pale Tom Brooke.

His would-be friend and life-saver, The Other, a gentle, bearded but naive Jack Laskey, wants to understand.

I Am The Wind by Norway's Jon Fosse – translated into unpunctuated free verse by Simon Stephens – is a bleak two-hander about incurable gloominess. On the upside, this is the long-awaited UK theatre debut of the legendary French director Patrice Chéreau: a production stunningly staged on a strip of sand pooling with dark water.

The downer, in terms of artistic calibre, is Fosse's dialogue. During the first 10 minutes, I sank into a slough of despond, not because The One's dismal mood inspired sympathy, but because of Fosse's stultifying repetitiveness. Here's The One again: "I turn into a rock/ and it gets/ the rock/ gets heavier and heavier/ I get so heavy that I can hardly move/ so heavy that I sink/ down and down/ down under the sea/ I sink/ down ...."

This is, surely, minimalism for halfwits, contriving to be at once linguistically bald and verbose. Perhaps Fosse is trying to capture the sensation of being in a psychological rut, depression's inertia, but he is in danger of dragging the whole enterprise down with him. Mercifully, though, Chéreau has come up with a fantastic coup de théâtre. A boat suddenly surges up from under the water, a great tilting raft of rusted metal which bears Laskey and Brooke out to sea. They're on a voyage now, an increasingly complex and gripping allegory of the unstable relationship which The Other has agreed to embark on with The One, either out of compassion or possibly unrequited love.

Raised on pivoting pistons, the raft is like a fairground waltzer in oceanic slow motion, or some monster from the deep. It bucks and swirls, cresting imaginary surges but listing violently as The One plays dangerous games and the power balance shifts.

This is mesmerising stuff, hydraulics being used to richly symbolic and menacing effect (and, on that score, blowing the West End's Chitty Chitty Bang Bang out of the water) Chéreau's young actors also prove outstanding. Plumbing the script for all it's worth, both are psychologically and physically haunting. Brooke slumps, cadaverously, in Laskey's drenched and exhausted arms, like a pietà. Then he rallies, with a demonic glint in his eye, leaping on to the rearing edge of the boat and luring The Other, his better half, to the brink of destruction.

Maybe Ibsen's Little Eyolf was lurking in the back of Fosse's mind – even if he momentarily forgot about his famous predecessor when declaring (in an IoS interview earlier this month) that naturalism was an un-Norwegian, "peculiarly English obsession".

In Anthony Biggs' revival of Ibsen's domestic tragedy from the 1890s, Imogen Stubbs' Rita and her husband, Alfred (Jonathan Cullen), are wracked with guilt. Their crippled little boy, Eyolf, drowns in the harbour, apparently lying on the bottom as if suicidally resigned, staring up from the depths. His parents never loved him properly, with Rita craving undivided, uxorious attention from Alfred. Her spouse is, in turn, hung up on his half-sister.

The lacerating realism of Ibsen's portrait of grief-stricken recriminations remains shockingly raw, even today. Additionally, art and life are here painfully compacted by the recent exposure of Stubbs' and Trevor Nunn's marital breakdown.

That said, her Rita's screaming rages too often seem operatically over the top in Jermyn Street's tiny auditorium. On the other hand, more fore-boding is required when the Rat Wife – a pest-drowning old witch – comes snooping around shortly before Eyolf's death. Biggs has obviously had to stage this on a shoestring, but his combination of period furnishings with chipboard is a glaring mismatch.

By comparison, Philip Massinger's The City Madam, a satire from 1632 revived by the RSC, is a splendiferous romp, awash with silver and gold finery. Its caricatured nouveau riche ladies and aristocratic suitors drip with silk ribbons and frilly lace as they cluster at the house of an ennobled city merchant and money-lender. Avarice is the shameless new creed. Closet debts and pilfered profits are rife. Yes, it's almost a 17th-century Enron.

The merchant's brother is a chastised dissolute called Luke Frugal (Jo Stone-Fewings) and he looks set to become a puritanical scourge, clutching a wooden crucifix. His preening, spendthrift sister-in-law (Sara Crowe) and his uppity nieces are certainly due some retribution for treating him like dirt. Anyway, Luke may yet prove a gold-grabbing hypocrite and be hoodwinked himself.

Dominic Hill's cast are buoyantly energised, with Stone-Fewings a mercurial lead, prefiguring Molière's imposter Tartuffe. As Luke's niece Anne, Lucy Briggs-Owen is a particularly droll grotesque, scarlet lips twitching in a white-powdered face, between a pretty pout and a snarl, as the eyelids bat brainlessly.

Too bad the play gets baggy with subplots, with bits and bobs nicked from Measure for Measure and Love's Labour's Lost, as well as the statutory masque. As this season's rediscovered gems go, The City Madam is no match for Cardenio – Shakespeare's "lost" play – being performed in rep by this ensemble on more polished form.

'I Am the Wind' (020-7922 2922) to 21 May; 'Little Eyolf' (020-7287 2875) to 28 May; 'The City Madam' (0844- 800 1110) to 4 October

Next Week:

Kate Bassett surveys Chekhov's The Cherry Orchard at the NT, with Conleth Hill and Zoë Wanamaker

Theatre Choice

Site-specific, immersive theatre turns into an epic hike. Fissure is a weekend-long walk through the Yorkshire Dales, above (20-22 May) promising waterways, peaks and caves, with surprise storytellers and choirs. The story of a woman's death fuses with the landscape to create a new legend of the underworld and rebirth (artevents.info).

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies