How a Hollywood computer made the stick of celery redundant

For more than 70 years, Foley artists have knocked coconut shells together, snapped vegetables and stamped in gravel pits to provide films with their sound effects. To them, a stick of celery or a frozen lettuce is not the staple of a decent salad but a bone ready to be broken. A heavy staple gun becomes a .44 Magnum, and scrunched cellophane a crackling log fire.

In the hands of an expert soundman, a pair of gloves produces the flapping of wings, squelching soapy hands conjure gory fight scenes, and the sound of actors smooching is given added lustre by the technician getting amorous with the side of his own wrist.

These traditional techniques have persisted even as cinematic visual effects have undergone multiple revolutions. Even today's most high-tech films like Toy Story 3, with their computer-generated imagery, still rely on the plain old Foley artist, who is often still using techniques pioneered in the first "talkies" (and remains consigned to the tail end of the credit reel).

However, if a team of American computer developers has its way, some of the practices perfected by these unsung heroes of the film industry could become obsolete.

The team will unveil a computer program this week which will generate sounds using similar modelling techniques to those employed in creating CGI graphics.

Their program builds a physical picture of the way sounds are created – for instance simulating the noise of a waterfall by constructing the component noises on a 3D virtual grid. If the new model proves successful, the existing, labour-intensive system of employing Foley artists to recreate every sound on a film could become largely automated.

Foley artists, while not resistant to change, believe that computer simulation can never completely replace the raw passion a human can bring to a soundtrack. "These newer ways of operating can remove a lot of the donkey-work from what we do but sound engineering in films is not simply about creating a sound, it is about creating an emotion using sound," said Pinewood Studios' resident Foley artist, Sandy Buchanan, whose recent film credits include Quantum of Solace and Tim Burton's adaptation of Alice in Wonderland.

"The real sound of a bone breaking would be quite boring if you just recorded it, but the sound of celery snapping, designed, produced and engineered by a professional, can be stomach-churning. For those sounds, the Foley artist cannot be replaced – but he will have to adapt."

Andy Farnell, a prominent sound technician who specialises in computer games, agrees: "My emotional response would be that you can never replace those techniques entirely."

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

The traditional art form is named after Jack Foley, who created the sound effects for Universal's first talkie, Showboat. The microphones used at the time could only accurately pick up dialogue, so background noises, like footsteps and doors closing, needed to be recreated in a studio. Foley began to develop ways of making these sounds and dubbing them over the film.

Since then, hundreds of ingenious techniques have been used to create almost all the background noises in Hollywood films, adding layers of texture that are taken for granted by viewers. Despite the ubiquity of these effects, they often go unnoticed – until the artists make a mistake.

The new system, developed by Hengchin Yeh, William Moss and colleagues at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, synthesises sounds associated with liquids flowing or splashing.

Mr Moss explained that, when water flows or waves break, noise is generated by the vibration of air bubbles. "You can model the bubbles – they just resonate at a certain frequency depending on their size. It is surprising but that is the primary source of sound in liquids," he told New Scientist, adding: "The physics is pretty easy."

The program models the vibration of these bubbles on a 3D grid, in the same way that 3D figures are made in CGI films. Until recently the technology has not been able to produce realistic simulations of complex sounds. But developers believe that they will soon be able to accurately recreate most of the noises they need.

Creating the sounds

Heavy staple gun, Gun noises

Snapping celery, Broken bones

Metal rake dragged across metal, Screeching car brakes

Heavy phone book, Body punching

Tearing a head of cabbage, Paper shredder

Cellophane, Crackling fire

Metal laundry tub filled with metal trays, empty fizzy drink cans, hubcaps, cutlery, knives..., A "crash tube" used to simulate collisions

Cassette tape ribbon, Grass or brush

Pair of gloves, Bird wings flapping

Hand soap, Squishing noises

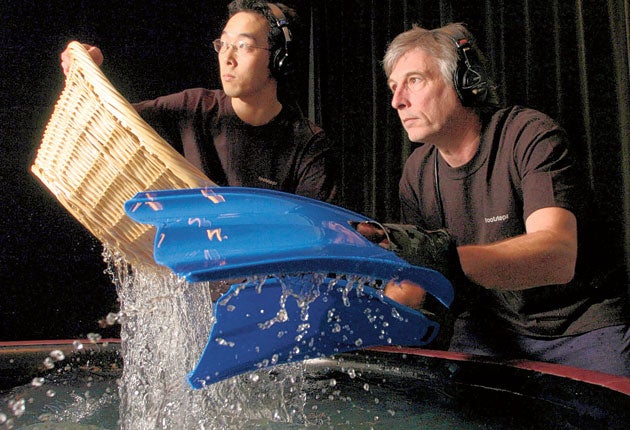

Wicker basket and flippers, Sea monster (as above)

The side of the wrist (wet), Adding gusto to kissing scenes

Leather jacket (twisted), Hammock swinging

Polystyrene, Sound of ice breaking

Rusty hinge/old chair, Creaking sound (hold against different surfaces for drastically different results)

Arrow/thin stick Whooshing noise or brush of clothing

Half-coconuts, stuffed with padding, Hoof noises (à la Monty Python)

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies