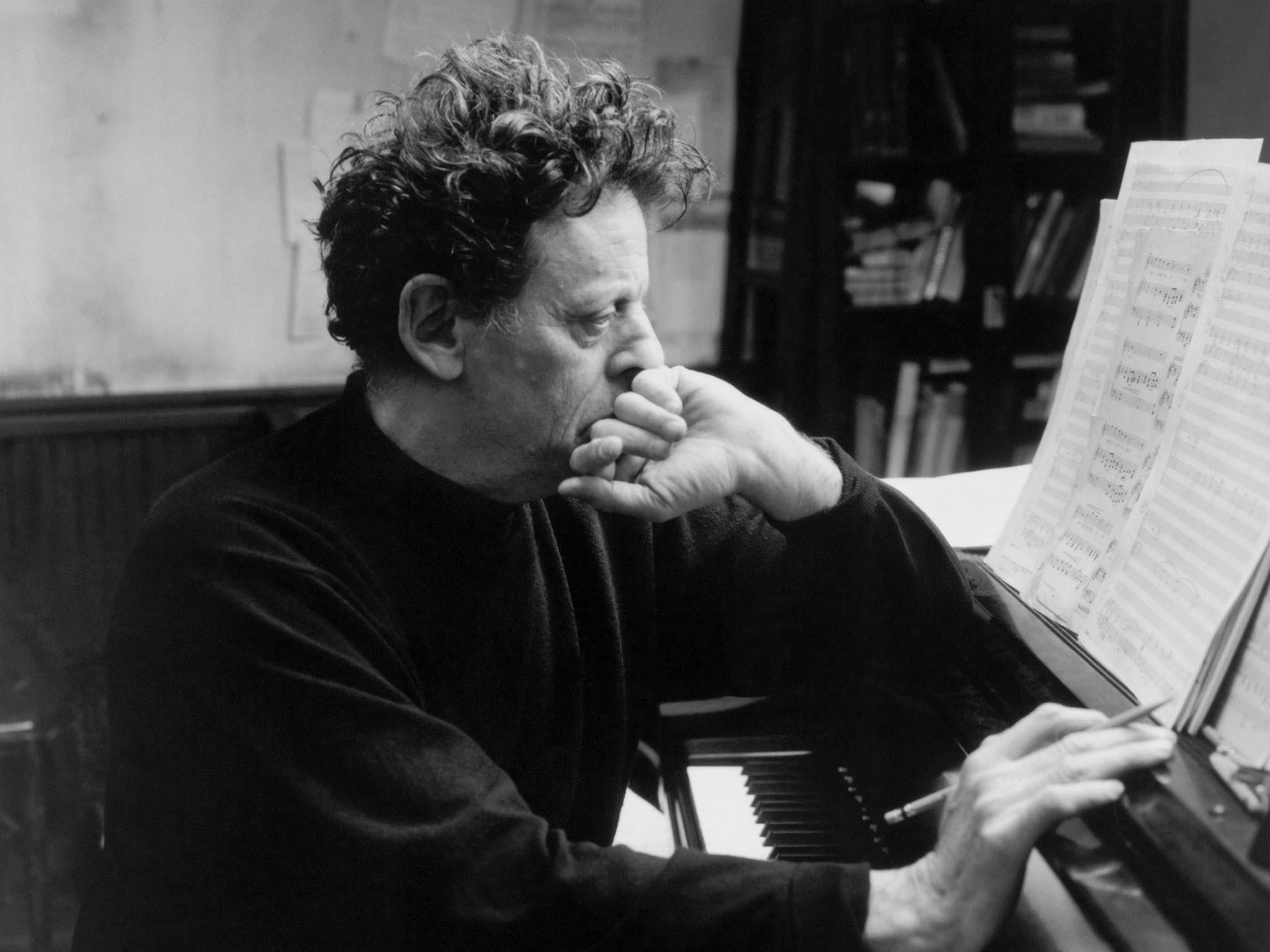

Words Without Music by Philip Glass, book review: Songs in the key of modern life

The one-time taxi driver's journey to becoming the genius who composed the soundtrack to our times is well worth the fare, says Boyd Tonkin

When Philip Glass made ends meet behind the wheel of a New York taxi in the mid-1970s, "drivers were regularly getting killed". He had a few scary encounters himself. However, one day the young composer had that Salvador Dali in the back of his cab: "moustache pointing straight up – the whole picture-perfect Dali". "Flabbergasted" by this apparition, the man who would embody modern music, just as Dali had embodied modern art, found himself "completely tongue-tied".

He had more to say to Martin Scorsese, both fan and friend. When director and composer collaborated on Kundun, Scorsese's epic about the Dalai Lama, the film-maker found that Glass had not yet seen his early masterpiece. "You didn't see Taxi Driver?" "Marty, I was a taxi driver… On my night off, the last thing I was going to do was see a movie called Taxi Driver." When Glass did, he found the feral cast "exactly like the people I knew who worked at Dover Garage".

As the soundtrack of films from The Truman Show to The Hours to Notes on a Scandal, or as the ubiquitous bought-in backing track to TV documentaries, the musical landscape of Glass intrigues and enchants the ears of people who know nothing about the contemporary classical scene. Breaking with the 12-tone Modernist orthodoxy of musical education, the young seeker had plunged deep and early into his triple sources of inspiration. They were the sounds of everyday American life; the avant-garde theatre, sculpture, art and film of Paris and New York; and the Asian traditions in music and spirituality that led to his commitment to Buddhism. Above all, Glass reveals in this wonderfully illuminating memoir that "the powerhouse of a place" that drove his imagination still chugs and pulses through his scores: "'What does your music sound like,' I'm often asked. 'It sounds like New York to me,' I say."

Glass was born in Baltimore in 1937, to a secular Jewish family who lived in a scruffy downtown neighbourhood. Mother Ida would become a librarian; father Ben helped run an auto-repair shop and then – crucially – started a record store. So young Philip not only heard music of all sorts, but sold it too. From the jazz greats (such as Parker and Coltrane) he still loves to Bartók and Schoenberg, his ears bathed in a supremely eclectic ocean of sound. He started lessons early, with the flute: symbol of pansy pretension to tough street-boys. When the goading went too far, "I just put my fists up and beat the crap out of the kid". Now, that's not a sentence you find in the autobiographies of too many revered composers.

The University of Chicago, which he attended as a precocious teenager, kick-started his immersion in a galaxy of art and thought – from bebop to existentialism, Big Bill Broonzy to Saul Bellow. That cultural voracity gives Glass's music a unique adaptive and absorbent power. On a train to Chicago, in one of the "epiphanies" that stud this relaxed and accessible testament, the young student began to hear the rhythm of the rails as a music of its own. Later, as a student of Ravi Shankar, Glass would learn from Indian classical method "the tools by which apparent chaos could be heard as an unending array of shifting beats and patterns". That night-train to Chicago also hinted in its drumbeats that "the sounds of daily life were entering me almost unnoticed".

At the Juilliard School in New York, the fledgling composer already knew that his destined track lay closer to Aaron Copland than to Pierre Boulez; to music that was "always meant to be heard and remembered". There he dived into the Greenwich Village arts scene that would sustain him over decades with its experimental audacity. But when he won a $750 prize, he spent it on a BMW R69 motorcycle and joined a gang of musical bikers. Via a bike trip he got to know his future wife, and collaborator long after their divorce, the theatre director JoAnne Akalaitis. The couple lived in 1960s Paris, with Glass on a Fulbright scholarship. So began the exposure to a succession of teachers, mentors and gurus to whom this memoir pays warm and surprisingly humble tribute. In Paris, Samuel Beckett and his circle helped to orient Glass's musical idiom: "this new music was born from the world of theatre". Study with the legendary teacher Nadia Boulanger lent him an all-purpose "toolbox", since "an authentic personal style cannot be achieved without a solid technique". Shankar grounded him in Indian classical forms. Comparing "Raviji" with Boulanger as masters, Glass remarks that: "One taught through love and the other through fear."

In the realm of the spirit, Glass and his wife embarked on a long overland trip to India – the one section, perhaps, in which this zestful and heartfelt book begins to flag. Already steeped in the practices of yoga, Glass was searching for fuller understanding of the "unseen world" that often thrums or glints behind his hypnotic patterns. When, in Kalimpong, he meets the Tibetan lama Tomo Geshe Rimpoche, "I knew that my search was over". Recounted with modesty and candour, Glass's Buddhist and "esoteric" affiliations may leave some readers by the Himalayan wayside. Much later, when his partner Candy Jernigan dies after a long illness movingly recalled, Glass stays with his guru in the Catskills. By the lake, Rimpoche slaps him on back and says: "That was a big lesson on impermanence." The bereaved Glass, "smiled slightly and nodded".

By the late 1980s, Glass's great trilogy of operas – Einstein on the Beach, Satyagraha and Akhnaten – had made a worldwide name that grows with every year. The scope of his music still astonishes. Listen, for instance, to his recent collected Piano Etudes played by Maki Namekawa: a keyboard summation and miniaturisation of his progress, in which a unique rhythmic and harmonic signature never impedes innovation. The composer who turned David Bowie's songs into a pair of symphonies and fused his method with the art of the Gambian griot Foday Musa Suso has forged "a new music world of diversity and heterodoxy". Big-hearted and open-minded, this irresistible memoir helps to show how Glass has channelled and transformed the sounds of our time.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies