Book review: The Speech, By Gary Younge Martin's Dream, By Clayborne Carson

Candace Allen – who was there – explores the legacy of a day, and a vision, that endure

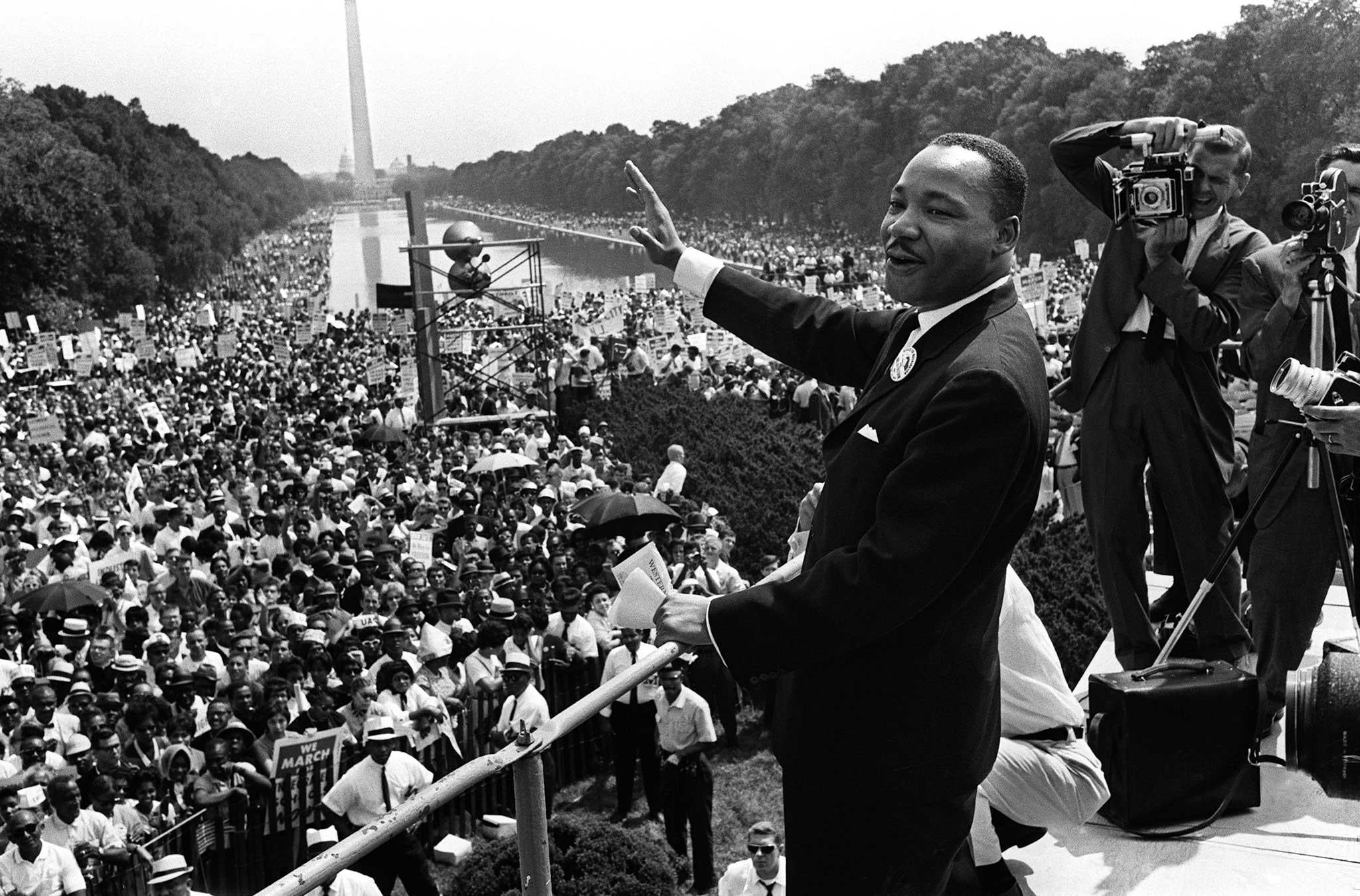

On 28 August 1963, when my family travelled down from Connecticut to take part in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, no one knew quite what to expect. Prior to that day the largest group to converge on the nation's capital had been, ironically, 50,000 members of the Ku Klux Klan in full hooded regalia in 1925. In 1941, union leader A Philip Randolph's threat of a Negro march to protest against war industry discrimination was narrowly averted by Franklin Roosevelt's Executive Order 8802.

Get money off these titles at the Independent book shop here and here

Now, 22 years later, after a season of mounting racial violence, beatings, bombings, firehoses and dogs, the murder of Medgar Evers and so many more, this notion – instigated by Randolph again – of tens, maybe hundreds of thousands, of Negroes marching together through the streets of Washington DC came accompanied by fears of violence. The federal and city governments feared rioting, which they were prepared to quell with force.

Washington being an essentially Southern city, many protesters feared the more normal pattern of white-on-black coercions. While, at 14 years old, I was oblivious to these fears, my father kept my brother and me very close. What occurred instead is the stuff of myth as well as history, at the apex of which was a speech that has taken on a life of its own.

The Speech by Guardian journalist Gary Younge is down and dirty, fleet of foot. Relying heavily on sources cited in his introduction, Younge skips rapidly through Civil Rights Movement highlights, with special attention to the volatilities of Alabama from 1962-63, before homing in on the massive undertaking that was the March itself. Some opponents, including the President and his Attorney-General brother Bobby Kennedy, felt that "The Negro" was pushing too hard, trying to go too fast.

Others, like Maya Angelou, then living in Ghana, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) activists on the frontlines in Alabama and Mississippi, were frustrated with the pace of non-violence and looked favourably toward Malcolm X's credo of "by any means necessary". Younge covers the organising partnership of Randolph and his brilliant, peripatetic and openly homosexual lieutenant Bayard Rustin, and the growing excitement as the idea became real. He comes into his own with the often highly entertaining saga of the clashing egos engaged in the drafting, slowing his momentum for a compelling, beat-by-beat analysis of a myth's creation: King's delivery of "the Speech" on the day.

After the whiplashing onslaught of the previous pages, this analysis is a welcome "pause that refreshes"; but, just as the March's euphoria was cruelly dispelled less than three weeks later with the deaths of four young girls in the Birmingham church bombing, we cannot rest for long. Younge has a tapas menu of concerns - why the deification of the Dream speech when King had and would deliver better?; the consequences of King's refusal to stay within the comfort zone of segregation and to question systemic economic inequalities and American militarism; the co-opting of King and the Dream by everyone from Tea Party conservatives to Barack Obama – and too little time and space.

Born in 1969, one year after King's assassination, and in Britain so not growing up surrounded by the ethos of an American movement, Younge has relied on interviews as well as secondary sources. That he respects King, is passionate about human rights and systemic hypocrisies, is abundantly clear, but there are times when I would have expected him to probe deeper and make finer distinctions, most particularly in regards to King's last years of marginalisation. He cites impatience with the Dream communicated by the likes of Stokely Carmichael, but neglects to explore the complexities of grief and anger felt and expressed in the streets and hearts of black people after King's death.

I suspect that the title Martin's Dream is a publisher's endeavour to capitalise on the March anniversary, for the subtitle – "My Journey and the Legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr" – is a far more accurate description of Clayborne Carson's memoir. Raised in the white enclave of Los Alamos, New Mexico, where his father worked in security at the eponymous nuclear laboratory, Carson at 19 made his way to the March on a whim, having no idea how strongly his life would come to be linked to the day's principal speaker.

Though attracted to the SNCC's frontline activities, economic and educational imperatives compel Carson to remain in Los Angeles where he dabbles in protest but then finds his niche, first as a reporter and then a historian of the Movement. Zeitgeist and luck as well as credentials situate him as a professor of African-American history at Stanford University, where after writing a dissertation and a book on SNCC, he is tapped by Coretta Scott King to annotate and publish her late husband's Augean stable of papers in 1985.

As a memoirist Carson is dispassionate to a fault, but beyond the internecine battles of the Papers Project, he contributes insights to the panoply of King lore. They include his own encounters with Stokely Carmichael and other Black Power advocates, which confirm their abiding respect and love of MLK despite their disagreements on process; revelations via the Martin-Coretta love letters that both Kings had an informed sympathy for socialism; and, uniquely, the adaptations of Carson's play on King by the Chinese National and a Palestinian theatre company, which offer thought-provoking views of the cross-cultural translation of King's legacy.

With a series of major Civil Rights anniversaries in the offing, the already large King oeuvre can be expected to expand. While neither of these efforts is a triumph, each contributes to our understanding of Martin Luther King beyond rose-tinted memories of a March and a Dream, emphasising that "Martin's Dream" was and is far more than one special day. As the man himself observed, "1963 is (and was) just the beginning."

Candace Allen is the author of 'Soul Music: the Pulse of Race and Music' (Gibson Square)

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies