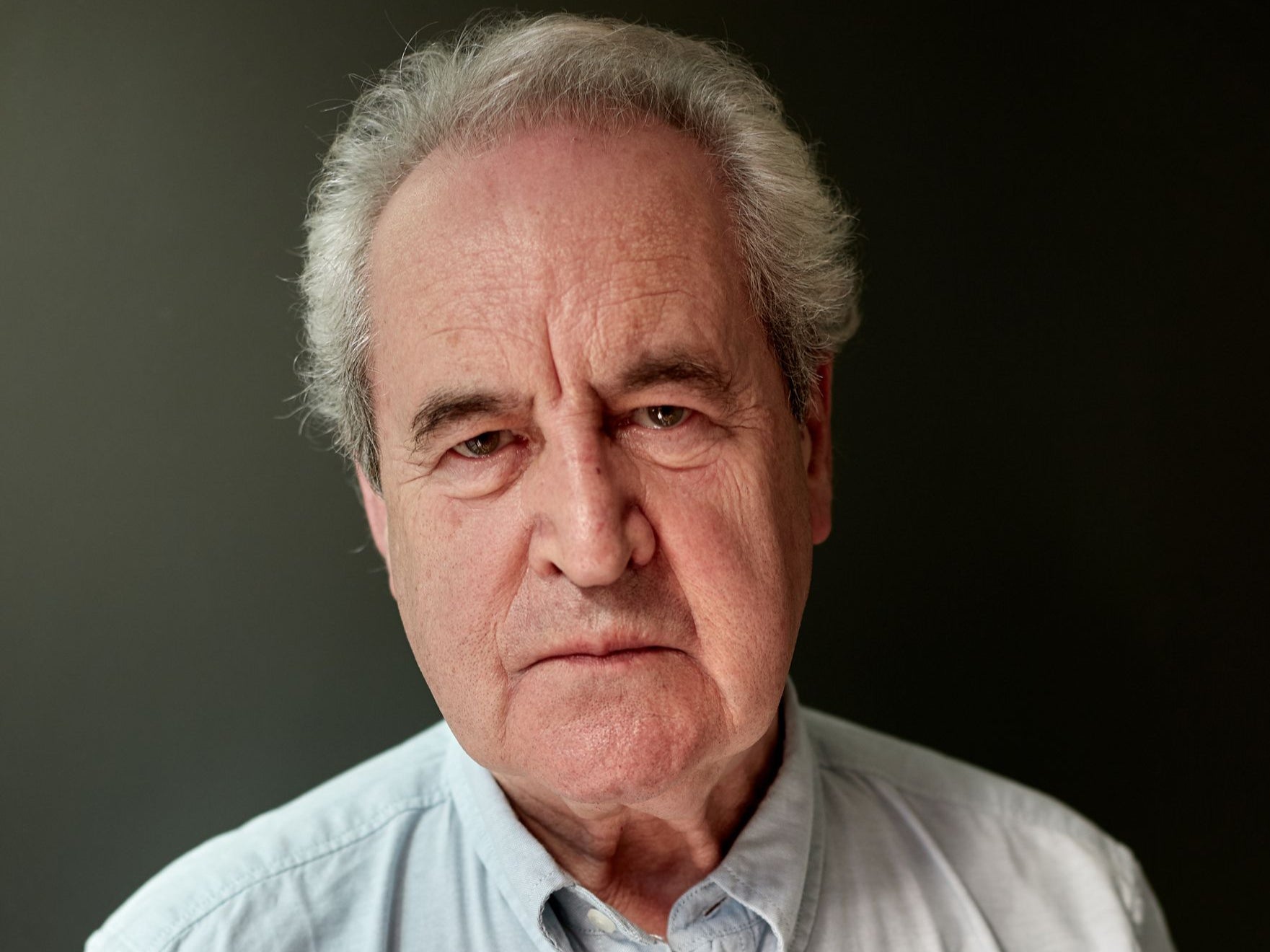

John Banville: ‘For 40 minutes I was a Nobel Prize winner’

The novelist has ditched his crime pseudonym for new thriller ‘April in Spain’, the follow-up to ‘Snow’, but he hasn’t thawed out just yet. He talks to Martin Chilton about pranks, pen names, the problem with Ireland – and what he really thinks about ‘The Wire’

John Banville says he “cannot see any point in being less than candid” about the truth of what it takes to be a writer. “We are monstrous creatures,” he says in his usual measured yet sardonic tone. “We are cannibals. We will consume and use anything.

“Nothing,” he adds, “is sacred.”

We chat early in the morning on Zoom. Banville, 75, is perched on the end of a bed strewn with books, and he smiles benignly as he presses home the point. “At a dinner party, I sometimes see people who have had a few glasses of wine and they look at me as they are talking away, and I can see them suddenly thinking, ‘I better stop, he will probably use this.’ And I would. I would for a good paragraph. We are ruthless, ruthless creatures.” Banville would know – with 30 novels to his name, he’s one of the world’s most revered literary voices.

“When my wife and I were together in the Seventies,” he continues, “and a big row was raging during a drive, I said, ‘That’s wonderful, can I use what you just said in that tirade?’ She said she thought I was even more of a monster and I said, ‘yes, I am. But can I use it?’ The Wire fellow is right. I am a whatever he called me.”

The Wire fellow is the HBO show’s creator, David Simon. In response to Banville’s claim in 2016 that no writer was a good father, Simon tweeted: “Speak for yourself, f***nuts.” Banville, whose latest crime novel April in Spain, was published on 7 October, recalled how he learned about the controversy. “One of the things I hate about Twitter is the childishness of the name, twittering, tweets and the whole baby talk of it. I was away that weekend and when I came back, my publishers rang and said: ‘How are you feeling, John?’ I said the trip was a bit wearing and all, and they said, ‘no, after the Twitter storm?’ I said, ‘what Twitter storm?’ I was told that people were angry about my comment that artists didn’t make good parents.”

The thoughtful, genial Banville with whom I talk is not the “arrogant, cold fish” described once by The New Yorker; however, it’s clear he is dismissive of any stranger’s opinion of him, favourable or not. “I don’t give a good God damn what people say about me,” he admits. “I don’t read reviews. I don’t read gossip about me. I don’t read praise. I don’t read anything about myself at all. I care nothing about the man behind The Wire. I exist in this little bubble, where as far as I am concerned there is just silence out there. I think everybody else should try that.”

Out of curiosity, though, I ask whether he’s actually seen Simon’s series. “I watched The Wire but I can’t understand what they are saying,” he replies. “I’m sure it’s a superb piece of opera, but I don’t get it.”

We chat a couple of days before the announcement of the winner of the 2021 Nobel Prize in Literature. Banville, who was born in Wexford on 8 December 1945, reacts good-naturedly when I ask how he now views the cruel hoax played on him a couple of years ago, when a man purporting to be from The Swedish Academy called the writer on his mobile – Banville was having a physiotherapy session at the time – to trick him into believing he’d won the book world’s most prestigious award.

“I laughed at the time. It was much more comic than tragic,” he says. “For 40 minutes I was a Nobel Prize winner. I phoned everyone in those 40 minutes, before my daughter rang me and said, ‘Dad, it’s been announced and it isn’t you’ [the award went to Austrian author Peter Handke]. Being Irish, I thought, ‘Ah, of course.’ Perhaps having that Irish sense of ill-fate helped me, but it was comic.” He says that one of his sons – from his first marriage to Janet Durham – even showed him a post from the “funny” fake Twitter account in his name, a captioned photograph that showed critic Fintan O’Toole and writer Colm Tóibín “splitting their sides laughing about the hoax”, with O’Toole asking fellow Irishman Tóibín, “did you put on the Swedish voice when you phoned him, tell me you did?”

Banville, who won the Booker Prize in 2005 with The Sea, was an outside bet for this year’s Nobel prize – Ladbrokes had him at 25/1, well ahead of English rivals AS Byatt and Ian McEwan – and although the award went to Tanzanian novelist Abdulrazak Gurnah, Banville’s two most recent crime novels, Snow and April in Spain, offered further reminders of why he is such a beautiful stylist and accomplished storyteller.

He credits the late Belgian author Georges Simenon as being “the father of me as a crime writer”. Both recent novels were published under his own name rather than Benjamin Black, a pen name he started using in 2006 for his crime fiction, separating it from such complex, sophisticated fiction as Doctor Copernicus, a novel about the 16th-century astronomer that won Banville the 1976 James Tait Black Memorial Prize. “In my very early books, which nobody reads any more thank God, I have a very gloomy, ironic-named character called Benjamin White, and I thought I would write as him. My agent suggested changing it to Black,” Banville explains. “Besides, with Black, you get nearer the top of librarians’ lists. Martin Amis would be above me… but still. I never wanted to hide behind a pseudonym, I just wanted readers to realise this wasn’t some kind of post-modernist joke I was playing. These were real crime books. Benjamin Black is killed off, except in Spanish-speaking countries. I am glad to be myself.”

He wrote April in Spain on a laptop, rather than in longhand, using his trusty fountain pen, adding deadpan: “That does mean there will be no manuscripts to sell.” The main villain in April in Spain, which features the recurring Banville character of 1950s Dublin pathologist Quirke, is a sociopathic working-class assassin called Terry Trice, who indulges in literary criticism of Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock while he’s on the way to murder people. “God knows where he came from, but I liked him,” remarks Banville. “He was amusing to write. When I invented him, I realised he was very like Pinkie Brown in Brighton Rock, so I gave him plenty of references to Pinkie. Terry and Pinkie: what a pair to meet on a dark night they would be.”

Banville says devising clever similes is one of the great pleasures of writing – “that sudden spark of something going off inside your head during the dullness of one’s day” – and bridles at criticism of his own opulent writing style. “People complain to me of the prolixity of my language and density of my style, and I say tyrants love simple language,” he says. “Don’t complain to me about my complex language. Simple language conveys simple truths. Complex truths require a different kind of language. If you listen to some of Donald Trump’s early speeches, when he was young, he was much more articulate. He deliberately dumbed himself down, because he saw that 240 million people responded to it.”

Snow and April in Spain feature police investigator St John Strafford, and corruption and scandal lurk in the shadows. Snow revolves around the mystery of a mutilated priest, sadistic Christian Brothers teachers and cover-ups of sexual abuse by the Catholic Church. The themes reflect the dark times Banville has seen in his homeland. Although he describes his own upbringing, as the son of a clerk in a large garage-supply business in Wexford, as peaceful and blessed, he admits: “I could see around me how horrible life was for so many children.”

He believes that some of the terrible events – the scandal over the Magdalene Laundries (notorious Catholic-run forced labour institutions for so-called “fallen women”), the brutality visited on children in Ireland’s Industrial Schools for neglected, abandoned or orphaned children, the sexual predator priests – are crimes that should have been investigated fully by “a truth commission.”

“There are many people who still deny the full depth of the horrors that took place in this country,” says Banville. “Everyone knew and didn’t know, in that peculiar way that perfectly decent people have of knowing and not knowing at the same time. We are not the only place, certainly not. You look at Nazi Germany, you look at Rwanda, Bosnia. Perfectly decent people ignoring the horrors being committed. So, thank you to all the people, mostly women academics, who fought and fought and fought for the truth to come out.”

Banville believes that Ireland “is now a better place”, citing the 2015 legalisation of same-sex marriage as an example. “I remember the day that same-sex marriage was allowed. It was a sunny morning and I looked round, and people were applauding,” says the writer. “There was a pink Volkswagen driving around with balloons and it was a kind of collective apology. Too late, but better late than never. I remember thinking, ‘Is this really Ireland?’ It’s not the Ireland I knew growing up.”

Banville rejects the idea of seeing the future through the simple lens of pessimism or optimism. “Things are as they are and will be as they will be,” he says. “Whether we think they are going to be better or worse is of no consequence; it isn’t really a subjective thing.

“I would banish the words optimism or pessimism,” he explains. “I like to think that I see the world as it is. It is a terrible place and it is also an exquisitely beautiful place. It is a cruel place; it is also extraordinarily tender.”

He acknowledges life has gotten stranger because of Covid-19, but says his own routine has remained pretty much as normal, sitting alone in a room writing all day long. “I know people have suffered terribly, and it must be dreadful for the young, but I did find the silence in the early lockdown days absolutely wondrous,” he adds. “I live about 10 miles outside Dublin and I was walking my dog on that first day in the fields and the city was completely silent and I thought, ‘My God, this is what I have always wanted’. One thing that amused me in the early months was seeing all those fathers out walking their babies and the look of torment on their faces, ‘Is this going to be life for years to come?’ I hope they learned something, being stuck at home with their children.”

Banville says he finds it “very interesting” that the pandemic hasn’t seen “a resurgence in religious devotion” in Ireland, adding: “People don’t seem to have gone back to the church, but if there were to be, for instance, a very serious total economic collapse, people going hungry, then the churches would be packed. It’s a very compelling message, you know, that the present is not as important as the real life to come after you die. I wish I could believe in that.”

He says there are two clearly defined John Banvilles: the writer at his desk, who has to be “resurrected every morning”, and the citizen. Can his family easily separate the two? “They certainly register the transition when Mr Hyde comes shambling out after scratching away at his pages and says, ‘give me a glass of wine, give me a glass of wine’, and then starts to become human and puts on his Dr Jekyll bow tie again. A long time ago [1986] I wrote a book called Mefisto and it was the most difficult book I have ever written, it nearly killed me. I had a sort of nervous breakdown when I was doing it, without noticing, and when I was writing the book I have just finished, my son said: ‘God almighty, this is as bad as Mefisto, isn’t it?’

The forthcoming book, a non-crime novel, took him nearly six years to complete. “It’s a very different kind of book and will probably sink like a stone, but I don’t care,” is all he says about it. “I thought I wouldn’t write that kind of book anymore, that I couldn’t sign on for another five or six years. Then one evening I was looking around and thought, ‘there was much more darkness around when I was a child; houses were darker, there were more dark corners and far less light pollution.’ I found myself writing ‘darknesses?’ I thought ‘Oh, Christ, I am pregnant again.’ Now I am doing another crime novel. I can’t be stopped.”

‘April in Spain’ by John Banville is published by Faber & Faber, £14.99

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies