Great art behind an iron curtain: Are all Chinese novelists 'state writers'

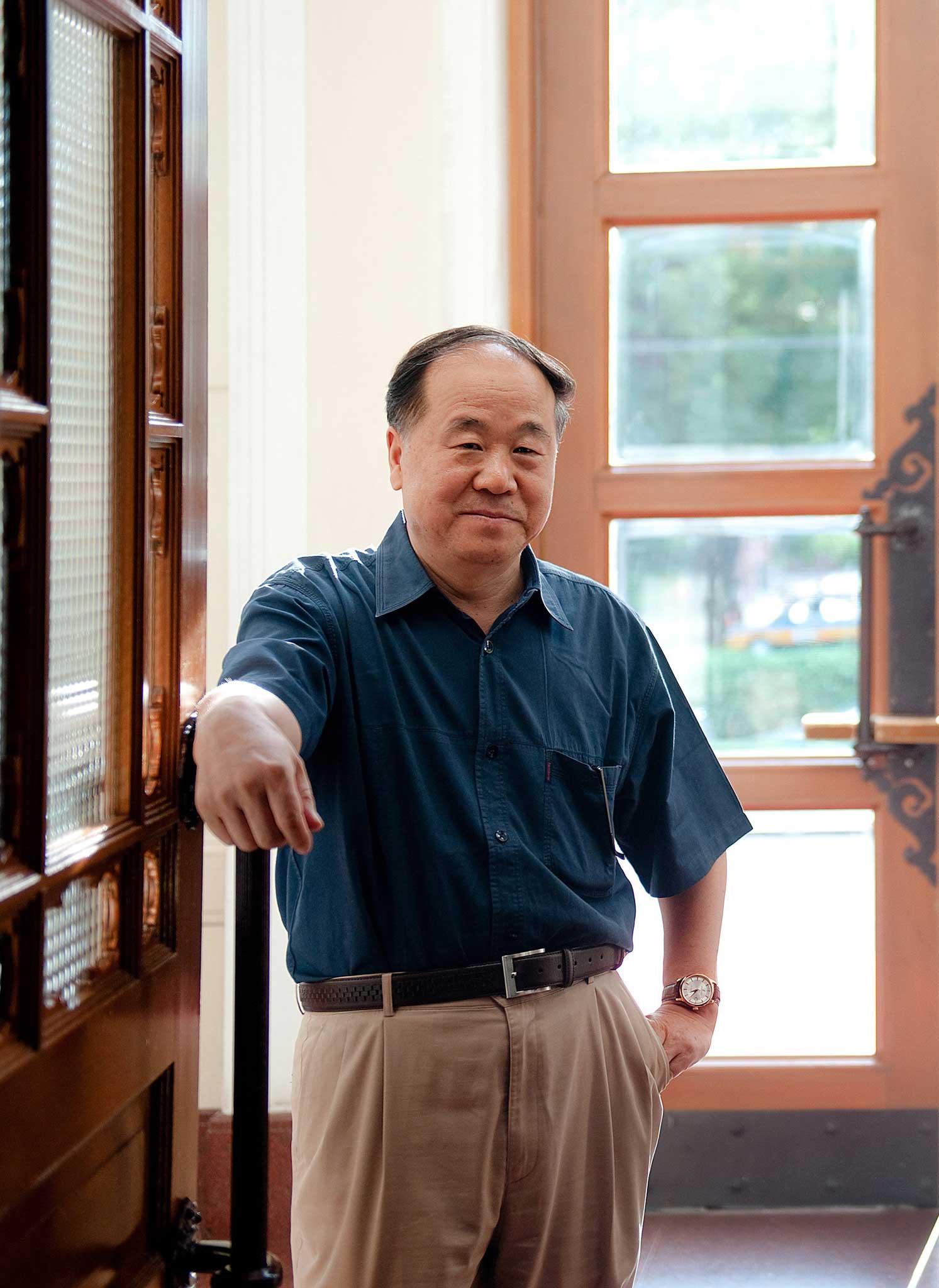

Mo Yan, who has won the Nobel Prize, has been criticised as such

December's England seems already to have sunk into a bitterly cold Orwell 1984 style darkness, but in the Swedish Academy, it appears to be shimmering, warm and cozy.

Last weekend, the Nobel Committee held the Nobel Prize ceremony for 2012. Mo Yan, the first official Chinese Literature Laureate made his speech. Mo spoke about his poverty ravaged childhood and how he became a writer: "What I should do was simplicity itself: Write my own stories in my own way. My way was that of the marketplace storyteller, with which I was so familiar, the way my grandfather and my grandmother and other village old-timers told stories."

In the same week that the Nobel Prize in Literature was given to the Chinese 'state writer' Mo Yan, the 'dissident writer' Liao Yiwu received the annual Peace Prize in Frankfurt. Best known for his essay collection, The Corpse Walker, Liao Yiwu protested about the Nobel Committee's decision: 'I am stunned; to me it is like a slap in the face... Mo Yan is a state poet.'

After four years imprisonment in a Chinese jail, in 2010 Liao Yiwu wrote a now famous open letter to the German Chancellor, Angela Merkel: "I'm writing this letter to you not only because you are the Chancellor of Germany, with considerable power to rally support when it comes to international affairs, but because you once lived in dictatorial East Germany, and perhaps you were trampled upon, humiliated, had your freedom restricted, and have some understanding of how I feel at this very moment. When the Berlin Wall fell you were 35 years old, I was 31 years old; that year the June Fourth massacre also happened; the night it happened I recited the long poem, Massacre. For this I was arrested and imprisoned…"

The indescribable personal suffering of artists in post-Mao China is reminiscent of other well-known cases of oppression and persecution: the fatwa on Salman Rushdie, Orhan Pamuk's struggles for freedom of speech in Turkey, Jafar Panahi's in Iran, to name a few. It seems natural that the western media pays attention to the 'dissident artists' rather than anonymous 'state artists'. But surely every artist is born from within a state, trained by the state, and has a complex discourse with the state, until the day the state choses to designate that artist an ideological enemy.

In times gone by, the state and the church governed as one, and powerful religious figures patronised artists like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, or Jan van Eyck for their own gain. In today's corporate capitalist state, an artist may well be complicit with power by espousing commercial value in their work. In an inevitably political society can anyone remain stateless for long? If being stateless is a possible choice, why would Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn decide to return to Russia at 75 after decades of living in the west?

In 2009, when China was featured as the guest country at the Frankfurt Book Fair, many in the Western book trade passed judgement on and dismissed the work of state writers attending the fair. It is likely that Western readers had little acquaintance with the stylistic differences between, say Mo Yan's hyper-realism and Wang Meng's social-realism, although only two years later one of these authors would go on to win the Nobel Prize.

Such is the unfamiliarity with the traditions of Asian literature amongst readers in the West. If we were still living in the Cold War, I could easily blame this on Western opposition to the ideological enemy: communism and the eastern bloc. But in our world of global communication and dissemination, I am disappointed by the fact that the there is so little knowledge about the great writers of the East, our equivalents of Hemingway, Joyce, or Jane Austen. How many more years have to pass before readers in the West will have the capacity to utter three Chinese writers' names without the need for googling them first? Or will the Western capitalistic mono-form swallow everything before these writers ever achieve due recognition?

I have huge respect for dissident writers like Liao and his absolutely uncompromising attitude as a political intellectual. But I do not agree with his opposition to Mo Yan's winning the Nobel Prize. In my opinion, to be a great state artist can be as great an achievement as being a dissident one. Take Shostakovich for example. It goes without saying that he did not find it easy to adhere to the expected behaviour of an artist in Stalin's USSR. That said, he received official accolades for his work and served as a state artist in the Supreme Russian Soviet Federal Socialist Republic and the USSR until his death.

Shostakovich chose to maintain as low a profile as possible between the premieres of his Fourth and Fifth symphonies, after the official ban of his 'formulistic' Fourth Symphony. The composer's response to his denunciation was the Fifth Symphony of 1937, which was considered at the time to be more conservative than his earlier works. But the ambiguity of this deeply beautiful piece led to its phenomenal success: many in the Leningrad audience had lost family members in mass executions during the German-Soviet war. It drove the public to tears and put Shostakovich back onto the Soviet landscape.

Now you may argue that an artist's genuine creativity can be seriously damaged by the state power and censorship. Of course, it happens all the time. But it's misguided to presume that in a totalitarian society it's a choice between artistic suicide or the personal suicide of political martyrdom. This year's winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature is a fantastic and prolific novelist. He is known for his epic books like Red Sorghum and Big Breast, Wide Hips, as well as his fabulist historical account of the consequence of Mao's land reforms, Life and Death Are Wearing Me Out. Mo Yan well deserved his prize. He offers the world not only the bitter documentation on the last century's tragic Chinese political movement, but also masterfully depicts an ambitious scroll of Asian society.

After the Nobel Committee's announcement, some activists and dissidents reacted angrily to his honouring because they felt he was too close to the authorities. In his home town of Shandong Mo Yan spoke to reporters and said, "if they had read my books they would understand that I took on a great deal of risk in my writing at that time and I was often under pressure. Many of the people who have criticised me are Communist party members themselves. They work within the system. I am writing from a China under Communist party leaders. But my work is not restricted by political parties." In another speech Mo Yan made after the announcement of the award he argued for the release of jailed poet Liu Xiaobo, who won the 2010 peace prize, much to the fury of Chinese authorities.

There is one other Chinese writer I want to mention who is neither a dissident nor a state author. Yan Lianke is one of the best contemporary Chinese writers living in Beijing. He is best known for his banned novel, Dream of Ding Village, which was shortlisted for the 2012 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize and the Man Asian Literary Prize. The novel is a painful account of the slow death of a village infected with HIV as a result of selling their blood. Yan is a typical case in the world of Eastern literature: he has received one of the highest official Chinese literary awards, the Lu Xun Prize, at the same time as being banned.

His early novel, Serve the People – describing an affair between a soldier and an army general's wife – led to the authorities removing 30,000 copies from sale. Despite his work being banned, Yan remains a professor of literature at Beijing People's University. Writers like him are truly impressive. As incisive as his social criticism is, he manages to protect his literary strength, instead of burning himself in front of the Square. Not unlike Shostakovich.

At the end of Shou Huo, Yan added an essay, a piece of literary criticism. (Of course this essay was taken out in the English edition, just as publishers so often do with Tolstoy's epilogue in War and Peace). In this essay Yan points out that realism in contemporary Chinese literature is the foremost criminal: "Tacky realism raped art, raped literature, raped our readers". His final line in that essay states, "we should treat realism as the burial ground of our writing, and if my books can become a part of those grave goods, I will be proud of my contribution to literature."

Art is beyond realism. Art is beyond geographical time and space. Art is obviously beyond dissidence. That should be our motto when we are trying to discover a powerful authentic form of art. The only moralistic concern in the artistic world perhaps is this: do we care more about the art produced by the artist, or the artist themselves? A humanist question. But I believe human destiny is beyond political struggle and historical condition. Which brings me to one of the most beautiful lines from Aldous Huxley's Brave New World: "I am not the captain of my soul; I am only its noisiest passenger."

Xiaolu Guo's fifth novel I Am China will be published by Chatto & Windus in 2013

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies