Edward Bawden, Bedford Gallery, Bedford

Like Dufy, Edward Bawden looks easy to imitate, until you try. Unlike the ebullient French painter of pleasure, however, Bawden could not have been more English – in the manner of his time.

Born in 1903, he developed his style, which never altered, in the interwar years, a time of austerity and innocence. His palette was muted, his compositions tidy, and the very few nudes he drew might have been produced by someone who had never seen any. He was happier with gardens, churches, and cats.

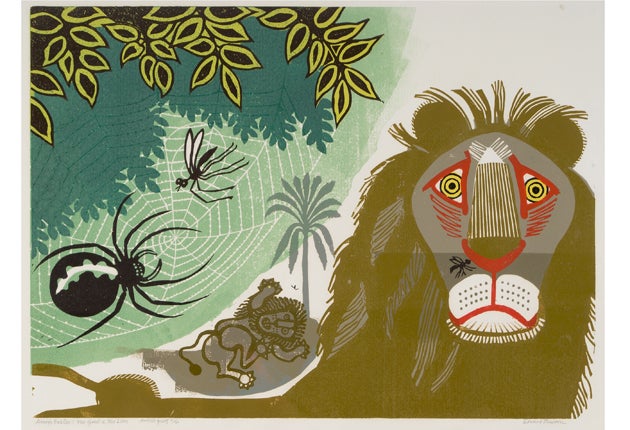

Bawden didn't work in oils but in watercolour. But he has always been better known for his linocuts, of which he was the 20th-century master, and for his commercial work. The last was a natural match for an artist whose figures at times resembled the monarchs of the bridge table. More often, they looked like clothespin dolls and the buildings around them like old-fashioned wooden toys. But Bawden created a world that, without being cloyingly nostalgic, was full of pawky charm, understated sophistication, and delicate fancy. He altered proportion and perspective in a way that owed much to the Cubists, and Miró's painting of a farm comes to mind when one sees the one Bawden did for the Festival of Britain. The result, however, never strayed too far from the style of the chapbook and primer.

Bawden, who died in 1989, left his archive to the Cecil Higgins Gallery, whose retrospective fills only two largish rooms and omits Bawden's war work but it sings with the vitality of his sharp draughtsmanship and the lively colours demanded by clients. The linoleum prints show how Bawden expanded the range of this humble medium with a variety of line and texture and an inventive whimsy – a sky filled with clouds, for instance, that could be inverted paving stones.

The characteristic device of Bawden's teasing yet reassuring style is a design of straight lines interrupted by irregular forms that add variety but do not disturb. In his print of Braintree Market, one curious cow pokes its head through the rails of a pen that keeps the others in check. And while the scientists at work in a post-war mural are engaged in God knows what, the little explosions they produce are held in place by a geometric framework. Design triumphs. All is well.

To 31 January (01234 353323)

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies