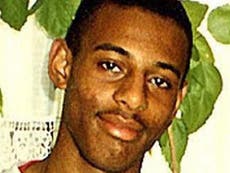

As a real tribute to Stephen Lawrence let's clear the pathways that could have given him a bright future

As a longstanding activist and campaigner I’m often asked if things have got better since I started out over 25 years ago. The truth is complicated

Stephen Lawrence’s murder had a profound effect on us all, and its aftermath forced the country to go through a difficult period of reflection never before seen in the UK.

When it was finally published, the Macpherson report legitimised what most of the BME community had felt and experienced for many years. In stating the view that there was “institutional racism” not just in the Met police but potentially in other public institutions too, the report was a political and societal game-changer.

As a longstanding activist and campaigner I’m often asked if things have got better since I started out over 25 years ago. Back then, in many areas, racism was raw: people bitterly really felt the inequalities, penalties and, at times, brutalities of being from an ethnic minority. So yes, I think there have been some profound changes. Of course, some areas are still lagging behind – but in others, we’ve seen positive change.

We’ve made strides in education. A good student, Stephen was on the cusp of adulthood and had dreams of becoming an architect. But in 1994, as he would have been starting university, only 3 per cent of entrants were black. In 2017, just over 40 per cent of black state school pupils aged 18 were offered a place in higher education.

In England alone, 88 per cent of Black Caribbean students went into sustained education, employment or training. And in January this year Brampton Manor, a school in the borough neighbouring Stephen’s own school, saw 41 of its students, the majority of whom are from ethnic minorities, receive offers from Oxbridge. This is welcome progress.

Still, the disparity between ethnic minority students going to university and being able to secure a job relevant to their study is too wide. It’s a fact the prime minister called out when she announced the Race At Work Charter last year.

If he was still with us today and working as an architect in London, Census 2011 data tells us that as a Black Caribbean man, Stephen would have been one of less than the 2% (aged 25-49) who were employed and working in a “professional occupation”. Given the journey so far, Census 2021 should be able to evidence real progress here.

But the current data also paints a disturbing and potentially regressive picture for the prospects of today’s children from different ethnic and social backgrounds.

Black families are most likely to live in the most deprived neighbourhoods and their children are three times more likely than white children to be permanently excluded from school. Young people from ethnic minority backgrounds make up nearly half of those in youth custody. And the BBC reports that, in London, black boys and young men are more likely to be victims as well as perpetrators of knife crime.

Reflecting on the more than quarter century that has passed since Stephen’s life was brutally cut short, it is frustrating to see how much has been achieved in some respects, and yet how little in others.

There is always a popular belief that issues of this magnitude need to be dealt with by all of us but particularly by “those in power”. The government’s Race Disparity Audit and Ethnicity facts and figures website were commissioned to expose the significant inequalities in outcomes that people from different ethnic and social backgrounds experience from public institutions and services. A bold and brave move, it continues to do this to good effect and is evolving to include new areas of societal concern.

But it also attests to another uncomfortable truth – we should be a lot further along than we are in addressing these disparities, especially when their impact can often be felt from childhood.

Many may be ready to point fingers – and I’m often the first – but it’s important to remember that while governments can lead, nothing changes if public services, businesses and communities don’t follow.

Poignantly, it is through the tireless efforts of his parents – who quietly established an eponymous charitable trust which has already supported many young people in London – that Stephen’s legacy has become so much more than the story of how his life was taken and what happened afterwards.

Now it’s on all of us to work together to take the example they have set nationwide. To truly honour his memory, and banish ethnic and social disparities, let there be more pathways out of deprivation, exclusion and criminality. Pathways that lead not just to jobs but to real, lasting careers. Pathways that fulfil young dreams and ambitions, create prosperity and a good quality of life – not just for this generation but for the next one and the one after that. Pathways just like the one he was on course to follow. Nothing would be a more fitting tribute.

Simon Woolley is one of the founders and Director of Operation Black Vote, and a former Commissioner for the Equality and Human Rights Commission

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies