Soldiers shouldn’t be allowed to get away with murder – but neither should the leaders who sent them to war

Defence minister Penny Mordaunt’s attempts to introduce an amnesty on historical prosecutions for British army veterans are designed to protect the British state and its leaders from international law

That war is a messy business is hardly a radical notion. The process of reparation and justice reflects this. It is chaotic, painful, emotionally charged and, at best, partial. These truths are borne out in the saga of the legacy prosecution cases that continue to emerge from Britain’s occupations of Iraq, Afghanistan and Northern Ireland.

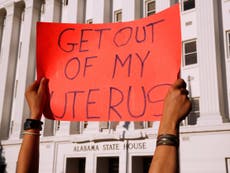

Yet there is more to these cases than just the pain of victims and their families. These allegations and the processes around them have become highly politicised – hijacked, if you will – and used by the government and the military in an effort to protect the British state against laws and conventions that might someday interfere with our customary pursuit of foreign policy goals through military violence.

In a remarkable sleight of hand, this process, which could include opting out of the European Convention on Human Rights in times of war, has been framed (with some success, at least among the hard of thinking) as a patriotic defence of our brave soldiers, sailors and airmen against liberal-leaning, ambulance-chasing lawyers acting on behalf of sinister, cynical foreigners.

The truth is that where there is evidence of criminality – and in many cases the evidence is ample (the Ministry of Defence has paid out on hundreds of cases) – prosecutions must take place. Grandstanding about an issue of this weight, as new defence minister Penny Mordaunt did today in what has become a Tory tradition, demeans not just the law but the victims of war.

Yet hidden somewhere in the words of successive Tory figures on this matter is an atom of truth, though not as they would understand it. There is a serious need to revise and reform how we deal with the legal ramifications of our wars and what happens in them.

This is especially so bearing in mind that even a theoretically “just” war would by its very nature involve war crimes of some kind. The Allies in the Second World War, we might recall, were absolutely as capable of shooting civilians and engaging in rape and pillage as their opponents were in the conduct of war-fighting operations.

Victims and family members of those killed and wounded in wars deserve justice. At the same time veterans and serving personnel, including myself, rail at the grotesque injustice of the junior ranks being the only ones faced with trials. Why is this the case when those in the lowest positions wield virtually no power over the conduct of the wars they are dispatched to fight? This is a situation which is entirely at odds with the judgments arrived at after the Second World War – the most vast and vicious war in human history.

If the legacy of allegations concerning killings and abuses, indeed the legacies of the wars themselves, are ever to be settled then we must look to the greatest, most far-reaching and effective war crimes trials of all, those at Nuremberg, where generals and politicians were put on trial. We should follow in their footsteps.

This does not mean that junior ranking service personnel who commit crimes should be effectively impervious to prosecution when they break the law (as Mordaunt foolishly suggested when she said cases over 10 years old should be put to bed). Many of our soldiers did break the law in Ireland and the Middle East and should have to face up to the consequences of their actions. Rather the Nuremburg rulings offer a clear-headed precedent that says those in war who wield the most power must bear the greatest burden of responsibility, and if they are found to have done wrong they must be subject to justice.

Fast forward to 2019 and look through the roll of those who have been in some way implicated in allegations. You will find a smattering of colonels and then private soldiers, corporals, sergeants, and so on. The coal-face workers of the military. Not a high-ranking leader among them. And a politician? Not a chance.

There is an old army proverb which assures us that “s*** rolls down the hill” when it comes to a soldier’s work and his punishment. Never was this truer than in these legacy cases when the generals of the day, men like Richard Dannatt (Iraq/Afghanistan) and Frank Kitson (Northern Ireland), as well as the politicians – Blair being the most obvious but Cameron’s Libya debacle merits attention – appear to be invulnerable to any real accountability for their involvement in the wars.

If we are serious about a just settlement in the wake of our wars of choice, then it must include holding to account not just young squaddies who misfire or murder in the horrific stress of war zones but the leaders who put them there and the officers who command them directly.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies