Orphaned in Syria’s civil war, how a refugee boy defied the odds to study in the UK

In Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley, Richard Hall meets a Syrian refugee who won a prestigious scholarship at a UK boarding school

There were many times throughout his life when 17-year-old Nour could have become just another grim statistic. The numbers were always against him.

He was a young boy when the Syrian war began, and when his hometown of Moadamyeh was bombed and besieged by government forces.

He could easily have become one of the more than 4,859 children who have been killed in Syria.

When his parents were killed within a month of each other, and he joined the ranks of more than 100,000 other orphans – that number too could have come to define him.

And when he fled to neighbouring Lebanon, and had to work two jobs to survive, he could have fallen into the more than 50 per cent of Syrian refugee children who did not attend school.

Even after making it that far, he might have been one of the 488,000 Syrian children who remain trapped in Lebanon – part of a lost generation with little hope of escape.

The precious objects bringing comfort to Syrian refugees

Show all 26But instead, through sheer grit and determination, he became the exception to the rule. This week, after a long and exhaustive selection process, he touched down in the UK to take up a scholarship at a prestigious boarding school in Wales.

In doing so, he became one of only a handful of Syrian refugees to make it to the UK without being part of a resettlement programme and with no help from the government.

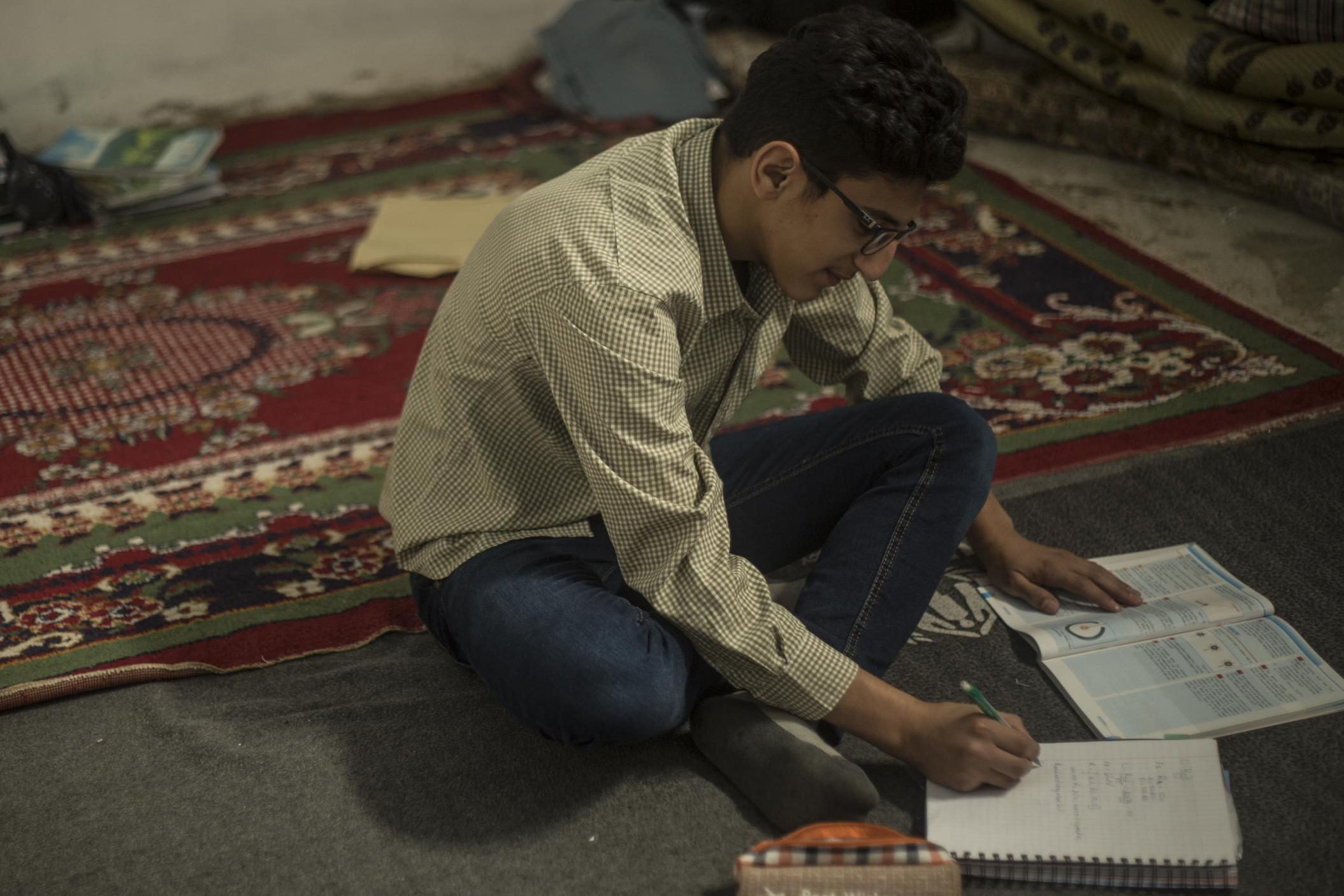

“I never dreamed I would be successful,” he says, speaking to The Independent in his now-empty apartment in the town of Bar Elias, just days before he is due to leave for the UK.

“At the beginning, when I first applied, I was really upset and miserable and hopeless. There are lots of programmes and scholarships like this. I was applying, but I was pretty sure it was not going to make any difference.”

It is easy to see why Nour was so pessimistic. The town of Bar Elias, where he has spent the last three years of his life, is home to thousands of refugees from neighbouring Syria. It sits just off the main road between Beirut and Damascus, around 10 miles from the Syrian border.

Refugee camps surround the town, and every winter those camps flood with water from the rain that feeds Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley.

In summer, the tents are baked from the blazing sun and Syrian children work the fields, filling the potato sacks they carry on their backs.

By the time Nour arrived in Lebanon, he had already been through so much. Seven years ago, when he was 10-years-old, his mother was killed by an airstrike that hit their neighbourhood. Less than a month later, his father suffered the same fate.

Nour was taken into the care of his brother, before he too was killed a year later. He was left with two sisters, but they were soon married and unable to care for him. He was on his way to an orphanage when a cousin stepped in to bring him to Lebanon.

Nour’s love of school kept him going. He was a good student in Syria and desperately wanted to carry on studying in Lebanon, but as soon as he arrived he was put to work in his cousin’s dairy factory.

“I didn’t have any free time for myself,” he says. “I wanted to study English, but I didn’t even have time to read a book. My cousin wouldn’t let me study.”

The same is true of many Syrian children. According to the United Nations children’s charity, the average monthly income of refugee families in the Beqaa Valley is around $50 (£41), while their expenses are close to $120. The result is that many children are sent to work to make up the difference.

Nour was still going to school while working for his cousin, but his job was getting in the way.

“Living with him was a really hard part in my life,” he explains. “I was suffering so much. That’s why I decided to leave him and live on my own.”

So, at 15 years old, a refugee in a country where most Syrians were struggling to survive, he moved into a one-room apartment on his own. He found a job painting houses and on the weekend he worked in a restaurant chopping fruit.

“It was the worst place I have ever lived,” he says. “It didn’t have a door even. I was doing everything myself. Cooking, cleaning and studying. I worked during my time off to support myself. I was only thinking about surviving.”

There were other difficulties, too, not unique to Nour’s life. Eight years into Syria’s devastating civil war, more than a million refugees remain stuck in limbo here, too afraid to return home to a country still stricken by conflict, where forced conscription and arbitrary arrests are commonplace.

Lebanon was praised early on for its hospitality to Syrians, but as the war dragged on, pressure has increased for them to leave. Evictions and army raids on refugee camps are on the rise, towns have introduced curfews specifically for Syrians, and ministers and politicians have made repeated calls for them to go home.

A worsening Lebanese economy only added to these tensions. Nour felt that undercurrent of anger.

“I love Lebanon, but Lebanon doesn’t love me,” he says. “Being a Syrian in the Lebanese society is really hard. Even though you have really close friends, you can’t erase from his mind the idea that I’m a Syrian and you’re a Lebanese.

“I had friends for more than five years and sometimes they say something so racist to me, they really hurt me. Even though I was so integrated, they will still treat you like a foreigner.”

Nour did more than survive. In his high school exams, he achieved the 28th highest marks in the entire country.

Charity workers started to take notice. He began receiving some assistance from Save the Children to help him stay in school. In 2018, he was visited by its then CEO, the former Danish prime minister Helle Thorning-Schmidt. The meeting would have a profound impact on the course of his life.

“She came to my house and she suggested that I apply to a boarding school. I had no idea what a boarding school was,” he says. “She wrote the name of it on a piece of paper and a few months later I applied.”

The boarding school, which The Independent is not naming to protect Nour’s anonymity, offered a scholarship for refugees – but competition for the place was fierce. A gruelling process of online tests and interviews followed.

“After the first interview, I said, ‘I don’t care,’” Nour recalls. “I didn’t think it would go any further. When I realised that things were getting more serious, I started to think about it more and more.”

He waited and waited for news. When the day finally came, it was the worst possible timing. He was due to take three exams and he couldn’t keep his mind off what could be the biggest decision of his life.

“I woke up at 5am, I looked at my phone and found nothing,” Nour says. “I thought ‘oh my God, I have been rejected’. Then I remembered that the wifi was turned off. I turned it on and I found the email.

“I started shouting. I didn’t want to go to school to do the exams. I was writing and I was so sleepy. I couldn’t concentrate. I wanted to go home. I wanted to dance.”

While Nour’s story has a happy ending, there are some 2.5 million Syrian children scattered across the region who have little hope of following in his footsteps.

“Nour’s story illustrates how important education is for children,” says Allison Zelkowitz, Save the Children’s country director in Lebanon. “He fought against all odds to make it to the UK, and while we supported him throughout his application process, he did it by himself thanks to his remarkable will and high grades.

“But resettlement of Syrian refugees in countries outside of the region has decreased. The UK can play a key role to ensure that more resettlement places are accessible and to increase access to other pathways for refugees, such as student visas. Supporting learning can be a lifeline to some of the highest-performing Syrian refugees.”

It would be a nervous few months while he made preparations for his new life. There were still so many things that could go wrong. It is not uncommon for Syrians to be detained at Beirut’s airport for bureaucratic infractions and there was always the chance that he could face problems on the other end, in the UK.

As he sits beside his packed bags in his apartment, Nour is a bundle of excitement. He is fascinated with aviation, and airports especially, and has spent the last few weeks studying the layout of Heathrow Terminal 5, where he is due to land.

He doesn’t have a clear idea of what he wants to do after school, only that he wants to tell his story to as many people as possible.

“All I know about what I want to be in the future is that I want to express all my opinions,” he says. “When I was a kid I felt I was restricted by what I could say. I want to share my story. I don’t want to be in one place. I want to move.”

*Nour arrived in the UK this week and is now getting ready to start the school term.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies