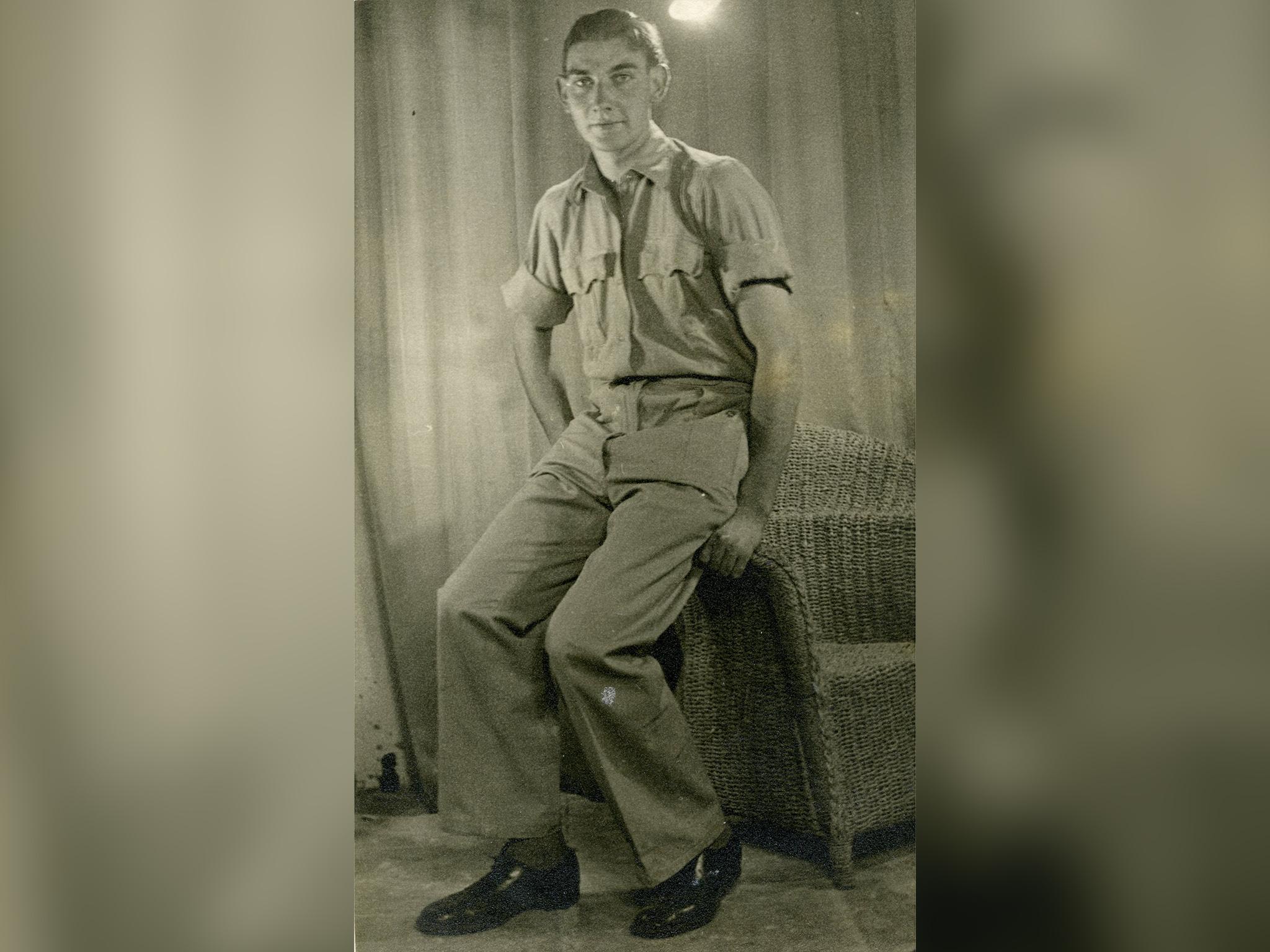

Ron Carrington: scientist whose research helped make antibiotics widely available

The Second World War veteran who served in Palestine went on to distinguish himself as a biochemist dedicated to making penicillin more accessible

Few people who met my father, Ron, after his retirement in 1987 would have had any idea of the focus and ambition that took him from a childhood in an unassuming part of Birmingham to the comfort and security of his comfortable retirement with my mother in Hove.

Nor would his modest and quiet humour have given any clue to his extraordinary academic success or career achievements. Those who met him would simply have encountered a civilised, considerate and thoroughly decent gentleman enjoying his quiet retirement with Vera, his wife of 67 years.

Ron’s father, Thomas Edwin Carrington, was a Coldstream Guard who survived four years in the trenches during the First World War and, as a result, never fully recovered the joie de vivre that my grandmother remembered when meeting him prior to his enlisting.

Ron was one of two children, six years older than his sister, Sylvia. His childhood home on Bolton Road, Small Heath, was next to a sweetshop owned by a Mr and Mrs Bunce.

His parents moved to Handsworth for the local grammar school, which he won a place at in 1936. They lived in a house with a weekly rent of £1.

When we visited my grandparents as children, I remember their neighbours talking with some awe of the new life that “our Ronnie” had in the world of science and industry – a life attributed by my father to an inspirational science teacher at school who injected him with a passion for science and discovery. But his progress towards that goal was far from easy.

During the bombing of Birmingham at the start of the Second World War, his parents evacuated him to Stroud where a kind “old man” and his younger wife who took him and another teenage boy in, taught him to play chess and revealed a far more relaxing and exciting life than was available in the hard world of Handsworth during the war.

It was a time of pleasure and discovery. But the harsh realities of Birmingham life were ever present. Their house in Handsworth was partially destroyed in an air raid and my grandfather was severely injured on another occasion during yet another bombing raid when he was patrolling as an air raid warden.

Things changed for my father in 1943 when he was conscripted into the RAF and sent to a North Wales recruitment centre.

His scientific and technical potential was immediately recognised and he was sent to Imperial College in London to train in radar communication.

He lived in a four-to-a-bedroom in Albert Hall Mansions, next door to the famous venue in Kensington, where the conscripted servicemen were offered free tickets to classical concerts. This was certainly the source of his love for classical music.

When the Doodlebugs came, Albert Hall Mansions was evacuated by the RAF and he was transferred to Cosford, near Wolverhampton, from where he was sent on to Palestine, to be based at the main airport at Lydda (now Lod).

His memories of Palestine were not positive. Being a serious and relatively self-contained young man, he was already keen to find a way of going to university and had no time for the military life. The RAF were probably no less excited by him than he was of them and he was finally demobbed in 1947 after an unsatisfactory time in which his demob date was extended due to the shortage of radar operators in Palestine.

It was at this point that his steely, but very quiet, sense of determination and ambition came to the fore. He remembered with some pride having written to his MP and had questions asked in parliament as to whether the state had the power to extend the national service of forces personnel with special technical skills. The petition was successful and he returned home after only a short extension of his stay.

But it was the war that was ultimately the making of him. Surviving on a government grant for returning servicemen, he gained a first class degree in biochemistry at the University of Birmingham, living at home with parents and passing his grant to his mother to cover his living costs.

Having met Vera at a dance, they married in 1951 and he moved on to PhD studies, gaining his doctorate in 1954 on “Transglycosidation by Aspergillus Niger (strain 152)”. I still have a copy of his PhD, its beautifully bound carbon paper pages devotedly typed by my mother in her evenings after working all day to support his studies and their rented room.

My father was undoubtedly a brilliant academic who moved relatively quickly from lecturing in biochemistry at Birmingham university to taking up a role in industry with Glaxo.

In 1961, he was recruited by Beecham, which had just established a new development centre in Worthing, leading a team of 18 in two small laboratories that were to become an international hub for the development of new antibiotics over the following decades.

He and his team bridged the chasm between discoveries made by researchers and the development of processes to enable antibiotics to be produced in large and cost-effective quantities.

Travel opportunities abounded, including to the United States, Belgium and Singapore.

Such was the international interest in the new world of antibiotics that he was even invited to Russia during the Cold War, where he believed he was followed by the KGB.

His work ultimately led to the development of advanced production techniques for some of the most successful semi-synthetic penicillins, including Amoxil and Augmentin: broad spectrum antibiotics.

Indeed, in his final (and only) serious illness, he was pleased that one of the antibiotics with which he was treated had been developed by him more than 40 years earlier.

Although he was a keen tennis player at university, he displayed no interest whatsoever in sport after he started work.

Though he conveyed no interest in sport to his sons, my brother Philip and I, we have strong memories of absorbing a different set of parental passions.

While our friends were playing football with their father at the weekend, we were learning to play chess and elaborate mental arithmetic games or “helping” him to build the most sophisticated stereo system that we had ever encountered; the kitchen table strewn with valves and incomprehensible electrical components.

The resulting “hi-fi” system was then utilised to play classical and jazz music at high volume, to the awe of visiting friends. While other children were learning from their father the names of 1966 World Cup football team, my father would bring home petri dishes to explain the science of microbes. These would be placed around the house to grow moulds that we would then identify and “treat” with mysterious organisms.

In retirement, he and my mother travelled extensively, but that process had started when we were relatively young children – not on exotic holidays, but in road trips, driving around Europe, visiting a different European capital every few days or walking in the Swiss mountains. He always said that his years in Palestine gave him all the sun that he ever needed and the few beach holidays we took were (on his part, but not ours) very reluctantly accepted.

Ron is survived by his wife Vera, their sons and grandchildren, Benjamin, Elicia, Isabella, Leo, Lydia, Olivia and Thomas.

Thomas Ronald (Ron) Carrington, scientist, born 16 September 1925, died 27 November 2018

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies