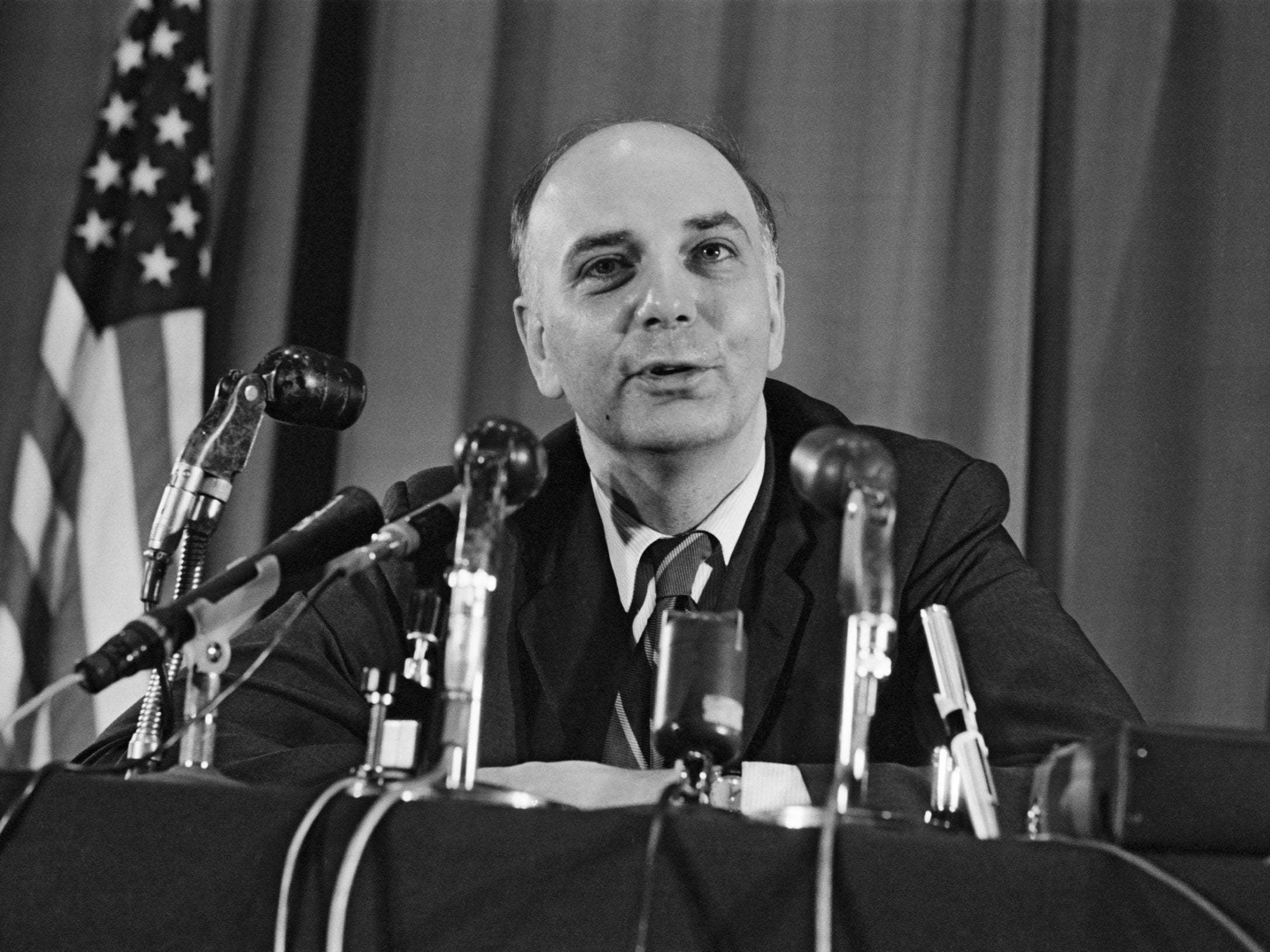

Paul Volcker: US Federal Reserve chief who shaped the key financial decisions of the late 20th century

America’s first celebrity central banker, Volcker worked under seven presidents and forged a reputation for independent-minded integrity

There may have been more consequential central bankers than Paul Volcker, though not many. Indubitably, however, none were more distinctive than the towering, cigar-chomping chair of the US Federal Reserve system, who helped to shape some of the most far-reaching financial decisions of the second half of the 20th century.

From the mid-1960s to the late 1980s, no international monetary or economic grouping was complete without the stooped figure of Volcker, 6ft 7in in his socks, his worn and inexpensive suits often flecked with ash, an incongruous mixture of the imperious and the everyday.

Volcker was the closest parallel in the US system to the British model of career civil servant. Presidents might come and go but Volcker was a constant, as a senior official at either the Fed or at the Treasury, who knew far more about the complex economic issues of the day than his nominal political masters.

As Richard Nixon’s Treasury under-secretary for monetary affairs, he was closely involved in the 1971 decision to end the convertibility of the dollar into gold that effectively ended the post-war Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates, and the subsequent devaluation of the dollar. Between 1975 and 1979, as president of the New York Federal Reserve Bank, he was the chief implementer of US monetary policy, and vital official liaison between America’s financial centre and other world markets.

But it was his eight years as chair of the Federal Reserve system between 1979 and 1987, during the Carter and Reagan administrations, that made him a household name. Paul Volcker, not Alan Greenspan, was America’s first celebrity central banker, and with good reason.

Appointed Fed chair at the height of the second oil crisis of the 1970s, Volcker imposed the brutal shock therapy to eradicate inflation that peaked in 1981 at 13.5 per cent. To do so, he replaced the traditional method of inflation rate targeting, with a rigid monetarism that drove interest rates at one point to 20 per cent and plunged the economy into recession. In the process he became one of the most famous, and reviled, figures in the country.

As families throughout the land felt the impact of Volcker’s policies, the magazine US News & World Report ranked this unelected bureaucrat the second most powerful person in America, behind only President Reagan himself.

Volcker acquired his taste for public service from his father, a highly respected municipal official in Teaneck, New Jersey. He graduated from Princeton in 1949, and took a masters at Harvard in public administration, followed by a two-year fellowship at the London School of Economics.

By 1952 he was a research assistant at the New York Fed, and quickly gained a reputation as a brilliant thinker and long-term planner, before switching to the economics department of Chase Manhattan Bank, where he forged close ties with Chase’s then-president David Rockefeller. When Jimmy Carter named him to head the central bank, Volcker was seen as “Wall Street’s choice”, a symbol of conservative orthodoxy forced upon a weak president to restore confidence to markets.

Early in his tenure he declared that inflation had been “bad and perhaps worse than expected”, and announce a full-percentage-point rise in the discount rate to a record 12 per cent. The Fed’s harsh monetary policies brought a surge in unemployment, and contributed to Carter’s crushing 1980 defeat at the hands of Ronald Reagan. Reagan too did not appreciate the central bank’s independent-minded chair, but he was equally powerless to do anything about it. Volcker was not one to tolerate political interference. And, most important, the medicine worked. By 1982 inflation had dropped to under 4 per cent, and the foundations laid for the solid growth of much of the 1980s and 1990s.

But a subtler price had been paid, as the inflation trauma reinforced a secular turn in public opinion against government and all its ways. The paradox would haunt Volcker. “I was brought up in an atmosphere of respecting government,” he said in 2000, “and respecting public servants, seems to me that’s the way it should be. But, everybody is very cynical these days.”

Volcker left the Fed in August 1987 at the end of a second four-year term and returned to New York, where he became chair of James Wolfensohn Inc, the investment banking company founded by the future president of the World Bank. A committed internationalist, he also resumed his association with the Rockefellers, and membership of the Trilateral Commission set up by David in 1973 as an informal global steering committee linking the US, Japan and Europe.

Volcker’s moral authority, international stature, and reputation for absolute integrity made him an elder statesman to whom troubled institutions turned. In 2002 he was called in to impose root and branch reform on Arthur Andersen, in an unsuccessful bid to save the accounting firm embroiled in the Enron scandal. Two years later Volcker was the natural choice to head the outside probe ordered by Kofi Annan into the United Nations’ Iraqi oil-for-food programme.

Volcker returned to the public eye with his 2008 endorsement of Barack Obama’s presidential campaign, and later counselled the president in his response to the financial crisis, proposing a key restriction on speculative activity by big banks (known as the “Volcker Rule”).

He is survived by his second wife Anke Dening, and two children from his first marriage.

Paul Adolph Volcker, economist and banker, born 5 September 1927, died 8 December 2019

Rupert Cornwell died in 2017

Additional reporting by Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies