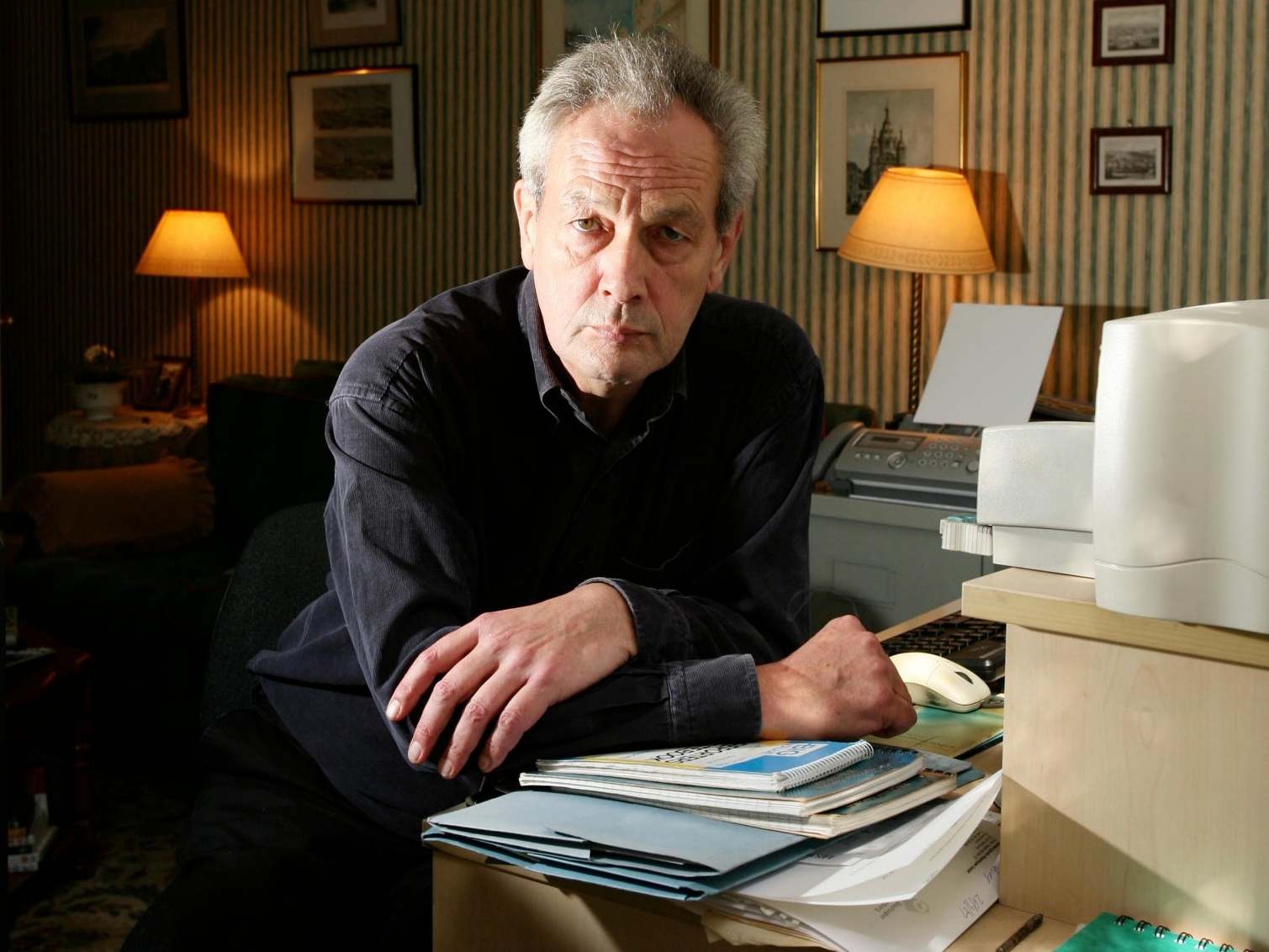

Norman Stone: Outspoken historian and writer whose work polarised academic opinion

A one-time speech-writer for Margaret Thatcher, his views on the Armenian Genocide and other matters aroused considerable hostility

Norman Stone, who has died aged 78, was a historian and writer whose colourful personality, outspokenness and political views created sharply polarised opinions of his lifestyle and work output.

Stone was born in Glasgow in 1941, the son of Mary, a teacher, and Norman, a lawyer who was killed the following year while flying a Spitfire on a training exercise. He attended the fee-paying Glasgow Academy on a scholarship. On going up to Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge in 1959 he had intended to study languages but soon switched to history, the subject in which he graduated with a first.

It was during his research into central European history in Vienna in 1962 that he met his first wife, Nicole Aubrey. They married in 1966 and had two sons, Rupert and Nick, now a novelist.

In his first – and best – book The Eastern Front 1914-1917, published in 1975, Stone demonstrates how the Russian army’s chaotic inefficiencies, rather than any economic shortage, were the cause of its retreat and eventual defeat. This meticulously researched magnum opus, which won the Wolfson Prize for History the following year, goes on to show how the turmoil of war led inexorably to the Russian revolution of 1917.

He followed this initial success with Hitler (1980), which fared less well with some reviewers and fellow historians. While AJP Taylor wrote that Stone had “drawn a portrait of Hitler which I endorse almost without reservation”, a New York Times reviewer, Alan Bullock, noted: “At other times he shows little sympathy for the experience of a generation which he regards as bringing its troubles on itself because it could not see what is obvious, with hindsight, to him and everyone else today.”

Reviewing Europe Transformed 1878-1919 (1983) in The Spectator, John Keegan, said: “The general reader, after deep gulps of prose, will wonder why they were ever led to think that history is a dull subject. His fellow professionals will only be able to take his narrative in small doses, needing frequent pauses to think, snort or wriggle with envy.” While that rambling narrative, with its wayward anecdotes and multiple levels of asides, would certainly please some, others would find it an irritant and a distraction from his central arguments of historical fact.

Stone had been a lifelong Conservative voter, with the exception of a period opting for the Lib Dems during the leadership of Edward Heath, a man whom he despised. In March 1989, Margaret Thatcher convened a secret meeting of historians at Chequers to discuss the impending German reunification, which she vehemently opposed and sought to impede. Stone, who had previously written speeches for Thatcher, later recalled the words of reassurance he gave to the prime minister at the conclave, telling her: “East Germany was not an accretion of strength, but, rather, 12 enormous Liverpools, handed over to the West Germans in a tatty cardboard box, with a great red ribbon round it, marked ‘From Russia with love’.”

In 1997, he unexpectedly quit the Oxford professorship of modern history and emigrated to Turkey, where he taught at Ankara and subsequently Bilkent universities. Asked about the reason for the move, he responded with wry humour: “You have to understand that, in the depth of my being, I’m a Scotsman and feel entirely at home in an enlightenment that has failed.” In his new role, he also joined the board of the Centre for Eurasian Studies (AVIM), a think tank whose policies include the denial of the Armenian Genocide.

Stone spoke eight languages to varying levels of fluency, including Hungarian. His last work, published last year, is Hungary: A Short History, a study of the country where he spent his final years.

His friend and former pupil, Professor Orlando Figes, said in a tribute that Stone was “a truly talented historian, inspiring teacher, the most kind and loyal of friends. He supervised my PhD and did more than anyone to help me become a historian. Europe Transformed is still one of the great books on European history.”

His second wife Christine Booker died in 2016. His two sons survive him.

Norman Stone, historian, born 8 March 1941, died 19 June 2019

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies