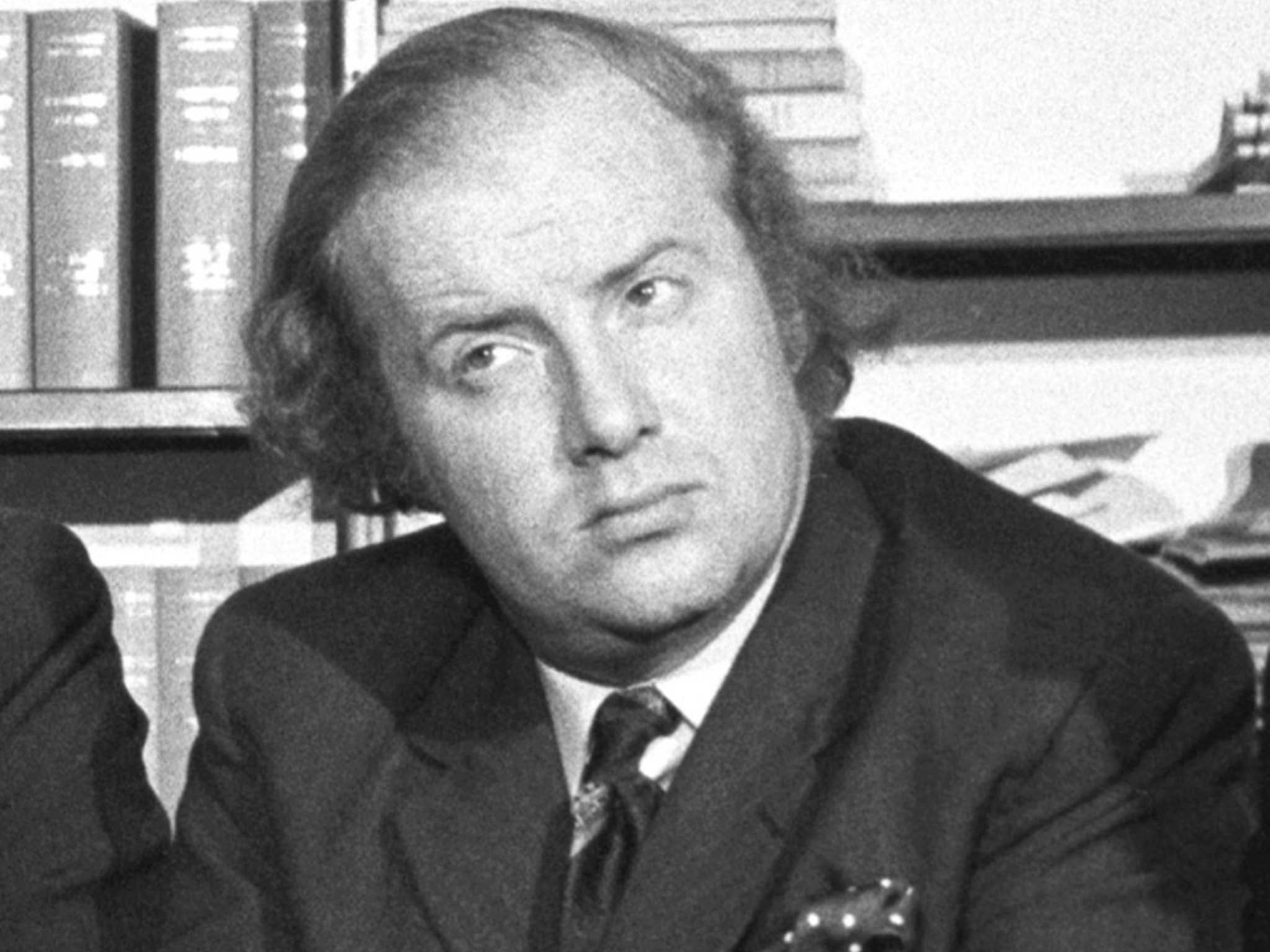

Ivan Cooper: Northern Ireland civil rights leader who took part in the march on Bloody Sunday

A co-founder of the SDLP, he was the most prominent Protestant in a campaign whose members were almost all Catholic

Ivan Cooper was a Northern Ireland civil rights leader and politician in the dangerous days of the late 1960s and early 1970s, when more than a thousand people died in a three-year period.

Cooper, who has died aged 75, was a minister in a short-lived local government in which Protestants and Catholics served together. In 1974 he was caught up in the widespread loyalist street protests against the sharing of power.

A year earlier one of Cooper’s colleagues in the nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party had been murdered by loyalist extremists who stabbed him 32 times. After that Cooper and others were issued with personal protection weapons.

The car in which Cooper and another minister, the late Paddy Devlin, were travelling drove into a roadblock manned by figures brandishing cudgels and other weapons. “Some of them ran menacingly towards us,” Devlin recalled in his memoir.

“A number of cars gave chase. We were terrified. Ivan and I both drew our guns when the confrontation developed and we sat with them on our laps for the rest of the very frightening journey.”

Dark past, bright future: The legacy of Bloody Sunday

Show all 9The loyalist action succeeded in bringing down the cross-community administration, in effect putting an end to Cooper’s political career. It was a career which had taken him from the streets to ministerial office in a hectic five-year period.

During that time he played a leading role in organising the 1972 march on what came to be known as Bloody Sunday, when 14 civilians were shot dead by paratroopers in Derry.

Later he said that for years he had been tormented with guilt: “I saw with my own eyes on that day innocent people being shot dead. I have lived with the burden of bringing people on to the streets, and people being gunned down in their city.”

As portrayed by actor James Nesbitt, Cooper was one of the central characters in the 2002 film Bloody Sunday. He stood out in politics as the most prominent Protestant in a civil rights campaign whose members were almost all Catholic. Its aims were opposed by many Protestants, with great determination.

Cooper was a particular hate figure for loyalists. He said there had been two attempts on his life, leading him to fit a steel door on his bedroom.

A member of a Church of Ireland family, Ivan Averill Cooper was born close to the village of Claudy near Derry in 1944, later moving to the city to work as a manager in a shirt factory. He readily mixed with Catholics, recalling that he and half a dozen other Protestants played football in the pre-Troubles Bogside before it became a republican stronghold.

In his earliest political days he was a member of the ruling Ulster Unionist Party before embarking on an odyssey which took him first to a mixed labour party and then to the civil rights movement.

At the age of 24 Cooper was elected chair of the Derry Citizens’ Action Committee, which complained that the unionist government systematically discriminated against Catholics. Cooper took part in innumerable meetings, protests, sit-downs and demos as the civil rights drive gathered momentum behind the slogan: “One man – one vote.”

He later explained: “The vote was tied to houses so the unionists just simply didn’t build any houses for the Catholic population. There were terrible housing conditions but they wouldn’t build houses because that would have created imbalance in the council. There were extremely high infant mortality rates, and people living in absolute squalor.”

A game-changing moment came when television cameras showed police dealing roughly with marchers. According to Cooper: “We were batoned and batoned very extremely. A police sergeant, a neighbour of mine, asked me what I was doing with ‘that pack of Fenians’ and gave me a couple of thumps with a baton. I didn’t get terribly badly injured but I was soaked by water cannon.”

While the campaign stirred widespread sympathy in Britain and internationally, its early unity splintered with some elements opting for the physical force approach of the IRA and Sinn Fein. But Cooper and others founded a new grouping, the SDLP, which attracted much electoral support – he himself proved a particularly popular vote-getter. The party rejected violence: one of his refrains was that “there is no political philosophy that is worth one drop of blood”.

As violence spiralled, Westminster, concluding that unionist majority rule had to end, created a new power-sharing arrangement with the SDLP as its nationalist component. Cooper took one of the party’s six posts in the new government, heading the community relations ministry. The executive’s short lifespan meant his administrative abilities were never tested: it lasted only five months before being brought down by the loyalist protests.

In the years of stalemate that followed, many politicians, including Cooper, found themselves out of a job. After that he made only occasional forays into politics, one of which saw him giving evidence at the Bloody Sunday inquiry. He was elated when it concluded that those shot were innocent, saying he finally felt his guilt lifting.

After his departure from frontline politics, he took part in a number of small business ventures, becoming among other things a consultant on bankruptcies. His friend Paddy Devlin wrote of him: “He was the best outdoor orator I ever heard, a splendid phrase-maker with a strong, resonant voice. He was a kindly man of great intelligence, courage and mental strength.”

Ivan Cooper, civil rights campaigner and politician, born 5 January 1944, died 26 June 2019

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies