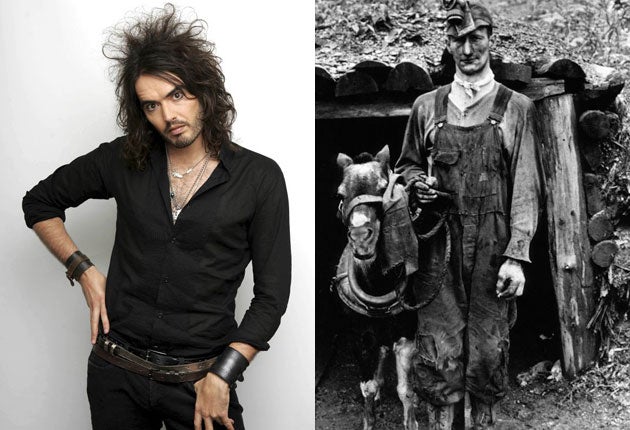

Austerity style: Men of Britain, put down your hair gel

...and pick up your shovels – because with hard times ahead, man-bag-clutching metrosexuality is out, and old-fashioned machismo is flexing its muscles once again

What is the correct response to a sudden straitening of circumstances? More specifically, what is the manly response? Is it one final, hysterical, shop-till-you-drop sweep of the Selfridges menswear department, girlish tears streaking our moisturised cheeks? Should the pretty boys of Britain unite for a mass bonfire of gym membership cards, interiors catalogues and cookery-show box-sets, to mark the passing of an era? Or could the correct response to global economic meltdown just possibly be something a bit more butch?

There is a growing suspicion that the current financial crisis might function as a metaphorical call to arms for British males, encouraging us pick up our spades, trowels and toolkits. Perhaps the question men will ask of each other on first meeting will be, "Can I borrow a screwdriver?" rather than "Ooh, nice scarf. Where's it from?" Maybe we'll stop calling our newborn sons Rio and Rocco and start naming them Stanley and Wilf.

Of all the many effects of the current global economic meltdown – the plunge in property prices, inflation, rising unemployment – perhaps the greatest change will be in attitudes and, as a result, in behaviour. For men, this change could even be epochal: we may be witnessing a return to the virtues and values of an earlier generation. No one – no one sensible – would advocate a regression to the days when men were men, women were downtrodden and children were terrified, but perhaps, in tough times, some stiffening of masculine sinew is required. Maybe it's time to put some hair back on the nation's chest. Perhaps the word "product" will once again indicate something we make, rather than something we wear in our hair.

After all, being pleasantly fragrant and waspishly witty is all very well if one's life is measured out in cocktail glasses and swizzle-sticks, but it's not much help when one's tilling the allotment. We are shortly to arrive at a point where, for the first time in a long time, a chap will be judged on his ability to repair electrical goods, forage for food and supervise a community bartering system. "Hard times call for hard men," says the writer Tony Parsons, who has repeatedly expressed the view that contemporary British men have lost touch with the values that once defined them: stoicism, thrift, fortitude, selflessness.

"This idea that we don't need real men, men who make things, that all we need is pinstriped spivs who gamble with other people's money, all that's gone," says Parsons, building up a very manly head of steam. The trouble is, he says, "we're completely unprepared. We've grown used to prosperity. We think we can just hire someone else to do all the hard work." He contrasts the manicured males of today with the fellows of the 1940s and 1950s, his father's generation. "They expected life to be hard," he says. "They expected to struggle. Their principle reason for living was to protect their families and provide for them. Since the Second World War, the principle reason for living has been to feel fulfilled and to enjoy yourself. My dad had a saying: any mug can spend it. We need to learn to carry ourselves like real men again."

Parsons is not alone. Gustav Temple is the editor of The Chap, a magazine that has long championed the presentational aesthetics, as well as the gentler manners of earlier generations. Temple is dedicated to promoting a vision of ' British men as "mild-mannered, genteel, upright and elegant". These are not qualities he associates with the current crop.

"There is definitely a feeling that, as Michael Caine put it in Alfie, men have become 'poncified'. The past decade has been one of selfishness, self-aggrandisement, hoarding. I don't think there's been any sense of unity, or much selflessness. Nor has there been much groundbreaking creativity. Men have become bland consumers."

Temple hopes that men will be forced to become self-reliant. "I found myself today wondering, 'How do you bake bread?' Because bread's bloody expensive, and I resent having to pay so much for it. Maybe I'm not alone. Maybe all of us will spend less time wandering around Habitat buying leather-lined wastepaper baskets and more time at home with hammer and nails, fixing things, being useful. People used to say, 'We need another war.' Maybe this is it." Except this is better because, as Temple puts it, "We don't all have to die."

Someone will have to die, though: the metrosexual. The imminent demise of this benighted species – the term was coined by Mark Simpson in The Independent as long ago as 1994 – has been forecast for some time. Earlier this year, the American columnist Kathleen Parker published a hand-wringing book, Save the Males: Why Men Matter, Why Women Should Care , arguing that feminism has neutered men, depriving us of our protective role in society.

"In the process of fashioning a more female-friendly world," writes Parker, "we have created a culture that is hostile towards males, contemptuous of masculinity and cynical about the delightful differences that make men irresistible, especially when something goes bump in the night."

Very kind of her, and all that, but the publication of Save the Males may have caused even the preening and primping variety of man to reflect that things had come to a pretty pass if we need a woman to explain to the world that, to bowlderise Parker's subtitle, "men matter".

Richard Benson, author of The Farm, which explores the erosion of traditional British rural societies – and the passing of an admirably phlegmatic if reticent masculinity – through the prism of his own family's loss of their Yorkshire pig farm, has been talking to another almost disappeared breed of hard men for his forthcoming book about the South Yorkshire coalfield. "I've spoken to a lot of men who used to be miners and now work in the retail and service industries, and their yearning for a more traditionally masculine, manufacturing-industry way of working is like a sort of pain for a lot of them," says Benson. "It's not to do with supposed 'simplicity' as much as comradeship. I suppose some nostalgia is to be expected, but it's also startling how many younger men, who never knew that life at all, have a deeply held respect for it as well. I recently asked a 30-year-old if his mates ever got fed up with or mocked old ex-miners going on about the past. He looked slightly surprised by the question, even affronted."

Away from such harsh realities, the media has instituted its own anti-metro backlash. But until recently retrosexuality – the promotion of a recidivist, back-to-basics blokeishness (heroes: Jeremy Clarkson, John Prescott, Ray Winstone) – has been largely cosmetic, just another pose for the metrosexual to strike. Witness Guy Ritchie and his ilk, pampered thespians all, peacocking about in their cloth caps and tweeds, or the grizzled movie hunk Russell Crowe, who appears intent, at all times, on assuring the world that he's less a professional actor than a moonlighting Aussie Rules footballer.

Mark Simpson was always careful to point out that he viewed the metrosexual as a mediated male – a man who locates masculinity in images presented to him in films, adverts and magazines and then attempts to ape them – rather than simply as someone overly concerned by his appearance. In this way, the retrosexual is actually just a metro in disguise: he is simply using different mediated images with which to construct his ersatz manly persona.

Lately, however, the signs of a real reversion to earlier male values have grown stronger. British TV's most iconic fictional male is Philip Glenister's DCI Gene Hunt, of Life on Mars and Ashes to Ashes, a violent bigot whose angry posturing has made him an unlikely international model of old-school machismo. "Don't move," orders Hunt. "You're surrounded by armed bastards!"

In the US, the defining image of televised machismo is provided by Mad Men's ladykilling Donald Draper. Meanwhile, the prime minister of Russia, having already been photographed indulging in a spot of shirtless fishing and heroically tranquilising a Siberian tiger, recently issued a testosterone-fuelled DVD entitled Let's Learn Judo with Vladimir Putin. David Walliams, perhaps the gayest straight man in Britain, swam the Channel to prove his undoubted macho bonafides.

Writing as a metrosexual – if, occasionally, a reluctant one (even I draw the line at series-linking Gossip Girl) – I find the thought of all this somewhat alarming. Norman Mailer, a writer-slash-silverback so dedicated to chest-beating displays of machismo that, according to his biographer Mary Dearborn, he once beat up a sailor because he believed the poor man had questioned the heterosexuality of his dog, had much to say on the perils of toughism.

"Machismo is not the easiest cloak to wear," wrote Mailer. "Machismo is a ladder, and there's always a guy who's more macho than you coming up that ladder... Macho means taking the dares that come your way, and if you take every dare that comes your way, sooner or later you're gonna be dead."

It's edifying, with that in mind, to remember that hard times don't always call for hard men. Often, financial gloom and social strife has sparked glittering pockets of decadence in which male glamour, even effeminacy, has been prized over more manly arts. One thinks of Christopher Isherwood's Weimar Germany, of course, but also early-1980s Britain, when jobless New Romantics scrimped and saved to make their own panto-dandy regalia. Perhaps, during the coming impoverishment, there will be a place for the gel-stuffed bathroom cabinet after all. I hope so.

What is certain is that men have an adjustment to make. In 1933, in the midst of the last great depression, Franklin D Roosevelt arrived in the White House determined to lead the way out of the economic crisis. His inaugural address is still inspiring today: "Happiness," he said, "lies not in the mere possession of money; it lies in the joy of achievement, in the thrill of creative effort. The joy and moral stimulation of work no longer must be forgotten in the mad chase of evanescent profits..."

There are those who will disagree, of course, but there is one well-known non-metrosexual who seems to have grown in stature and confidence during the current calamities. For all I know, Gordon Brown is a confirmed Clinique man who likes nothing better than a night in with Sarah and the kids, a sushi dinner and a salty rom-com on the widescreen. Maybe, even now, he's planning his next tribal tattoo and worrying about his tan lines. But I suspect not. It's hard to imagine the Prime Minister moisturising. He's stoic, he's saturnine, he's thrifty, he's hard-working and he's rarely looked happier or more secure than when facing economic turmoil.

"Our common difficulties," said Roosevelt in 1933, "are, thank God, only material things."

So you might not be able to afford a new kitchen. That doesn't mean you're any less of a man. It might even be the making of you. I'll see you at the hardware store. It's the new spa, apparently.

Alex Bilmes is features director of 'GQ'

The way we were: Bert Trautmann, retrosexual icon

You can watch the moment that elevated the Manchester City goalkeeper Bert Trautmann from mere famous footballer to enduring folk hero on YouTube. Just type in his name and click on the Pathé newsreel highlights of the 1956 FA Cup final between Trautmann's team and Birmingham City. With 15 minutes to go and the score at 3-1 in the Lancastrians' favour, Birmingham's Peter Murphy charges into the six-yard box. "Bert Trautmann pounces like a cat," says the commentator, as the goalie dives at Murphy's feet. "But what's happened? Trautmann's down. He's injured. Team-mates help Trautmann to his feet. He tells the trainer he's alright but the crowd can see his neck is hurting badly."

Trautmann played on, clearly dazed and in great pain, making crucial saves to maintain his side's lead. When he walked up to collect his winner's medal, his neck was noticeably crooked. Three days later (this bit's not on YouTube), an X-ray revealed that Trautmann's neck was broken.

Bernhard Carl Trautmann was born in Bremen, Germany, in October 1923. He joined the Luftwaffe as a teenager, served for three years on the Eastern Front, where he won five medals including the Iron Cross. He then transferred to the Western Front where he was taken as a POW by the British and transferred to a prison camp in Lancashire. In 1948 he was released and chose to settle in England, working as a farm hand and playing in goal for his local team, St Helens Town.

In 1949 he joined Manchester City. Thousands protested the signing of a former German soldier but Trautmann steadily won the City faithful over, eventually making 545 appearances between 1949 and 1964. These days, Trautmann lives in Spain with his third wife, Marlis. He continues to front the Trautmann Foundation, promoting Anglo-German understanding through football. Its slogan? "Courage Counts". It certainly did for Bert.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies