Sign up to Roisin O’Connor’s free weekly newsletter Now Hear This for the inside track on all things music Get our Now Hear This email for free

S ex Pistols bassist Sid Vicious was found dead in New York City on 2 February 1979, 40 years ago. It was less than four months after the death of his girlfriend, Nancy Spungen – and Vicious stood accused of murdering her in the bathroom of their suite at the Chelsea Hotel. But four decades on, what really happened in Room 100 still remains unclear.

The boy born John Simon Ritchie in Lewisham was only 21 when he died. He overdosed on heroin at a Greenwich Village party thrown to celebrate his release from the notorious Riker’s Island prison, a 55-day stay during which he had taken part in a – clearly ineffectual – drug rehabilitation programme.

Vicious had been held for assaulting Patti Smith’s brother Todd with a broken Heineken bottle at the Hurrah nightclub while out on bail following his arrest on suspicion of murdering Spungen.

She had died of a stab wound to the abdomen on 12 October 1978. Vicious’s fatal relapse at his release party meant he would never be convicted of her killing – although the certainty he was responsible has long lingered.

Show all 40 1 /40The 40 greatest song lyrics The 40 greatest song lyrics Nirvana – "All Apologies" “I wish I was like you / Easily amused / Find my nest of salt / Everything's my fault.” As headbangers with bleeding poets’ hearts, Nirvana were singular. Yet their slower songs have become unjustly obscured as the decades have rolled by. Has Kurt Cobain even more movingly articulated his angst and his anger than on the best song from their swan-song album, 1993’s In Utero? All Apologies – a mea culpa howled from the precipice – was directed to his wife, Courtney Love, and their baby daughter, Frances Bean. Six months later, Cobain would take his own life. No other composition more movingly articulates the despair that was set to devour him whole and the chest bursting love he felt for his family. Its circumstances are tragic yet its message – that loves lingers after we have gone – is uplifting. EP

Rex

The 40 greatest song lyrics Nine Inch Nails – "Hurt" “And you could have it all / My empire of dirt / I will let you down / I will make you hurt.” Trent Reznor’s lacerating diagnosis of his addiction to self-destruction – he has never confirmed whether or not the song refers to heroin use – would have an unlikely rebirth via Johnny Cash’s 2002 cover. But all of that ache, torrid lyricism and terrible beauty is already present and correct in Reznor’s original. EP

Getty

The 40 greatest song lyrics Joy Division – “Love Will Tear Us Apart” “Why is the bedroom so cold turned away on your side? / Is my timing that flawed, our respect run so dry?” Basking in its semi-official status as student disco anthem Joy Division’s biggest hit has arguably suffered from over-familiarity. Yet approached with fresh ears the aching humanity of Ian Curtis’s words glimmer darkly. His marriage was falling apart when he wrote the lyrics and he would take his own life shortly afterwards. But far from a ghoulish dispatch from the brink “Love Will Tear Us Apart” unfurls like a jangling guitar sonnet – sad and searing. EP

Paul Slattery/Retna

The 40 greatest song lyrics Arcade Fire – "Sprawl II (Mountains Beyond Mountains)" “They heard me singing and they told me to stop / Quit these pretentious things and just punch the clock.” Locating the dreamy underside of suburban ennui was perhaps the crowning achievement of Arcade Fire and their finest album, The Suburbs. Many artists have tried to speak to the asphyxiating conformity of life amid the manicured lawns and two-cars-in-the-drive purgatory of life in the sticks. But Arcade Fire articulated the frustrations and sense of something better just over the horizon that will be instantly familiar to anyone who grew up far away from the bright lights, “Sprawl II”’s keening synths gorgeous counterpointed by Régine Chassagne who sings like Bjork if Bjork stocked shelves in a supermarket while studying for her degree by night. EP

AFP/Getty Images

The 40 greatest song lyrics Beyonce – "Formation" "I like my baby hair, with baby hair and afros / I like my negro nose with Jackson Five nostrils / Earned all this money but they'll never take the country out me / I got hot sauce in my bag, swag." Beyonce had made politically charged statements before this, but “Formation” felt like her most explicit. The lyrics reclaim the power in her identity as a black woman from the deep south and have her bragging about her wealth and refusing to forget her roots. In a society that still judges women for boasting about their success, Beyonce owns it, and makes a point of asserting her power, including over men. “You might just be a black Bill Gates in the making,” she muses, but then decides, actually: “I might just be a black Bill Gates in the making.” RO

(Photo by Kevin Winter/Getty Images for Coachella)

The 40 greatest song lyrics Laura Marling – “Ghosts” “Lover, please do not / Fall to your knees / It’s not Like I believe in / Everlasting love.” Haunted folkie Marling was 16 when she wrote her break-out ballad – a divination of teenage heartache with a streak of flinty maturity that punches the listener in the gut. It’s one of the most coruscating anti-love songs of recent history – and a reminder that, Mumford and Sons notwithstanding – the mid 2000s nu-folk scene wasn’t quite the hellish fandango posterity has deemed it. EP

Alan McAteer

The 40 greatest song lyrics LCD Soundsystem – "Losing My Edge" “I’m losing my edge / To all the kids in Tokyo and Berlin / I'm losing my edge to the art-school Brooklynites in little jackets and borrowed nostalgia for the unremembered Eighties.” One of the best songs ever written about ageing and being forced to make peace with the person you are becoming. Long before the concept of the “hipster” had gone mainstream, the 30-something James Murphy was lamenting the cool kids – with their beards and their trucker hats – snapping at his heels. Coming out of his experiences as a too-cool-for school DJ in New York, the song functions perfectly well as a satire of Nathan Barley-type trendies. But, as Murphy desperately reels off all his cutting-edge influences, it’s the seam of genuine pain running through the lyrics that give it its universality. EP

Getty Images

The 40 greatest song lyrics Leonard Cohen – "So Long, Marianne" “Well you know that I love to live with you/ but you make me forget so very much / I forget to pray for the angels / and then the angels forget to pray for us.” You could fill an entire ledger with unforgettable Cohen lyrics – couplets that cut you in half like a samurai blade so that you don’t even notice what’s happened until you suddenly slide into pieces. “So Long, Marianne” was devoted to his lover, Marianne Jensen, whom he met on the Greek Island of Hydra in 1960. As the lyrics attest, they ultimately passed like ships in a long, sad night. She died three months before Cohen, in July 2016. Shortly beforehand he wrote to her his final farewell – a coda to the ballad that had come to define her in the wider world. “Know that I am so close behind you that if you stretch out your hand, I think you can reach mine... Goodbye old friend. Endless love, see you down the road.” EP

Getty

The 40 greatest song lyrics The Libertines – "Can't Stand Me Now" "An end fitting for the start / you twist and tore our love apart." The great pop bromance of our times came crashing down shortly after Carl Barât and Pete Doherty slung their arms around each others shoulders and delivered this incredible platonic love song. Has a break-up dirge ever stung so bitterly as when the Libertines duo counted the ways in which each had betrayed the other? Shortly afterwards, Doherty’s spiralling chemical habit would see him booted out of the group and he would become a national mascot for druggy excess – a sort of Danny Dyer with track-marks along his arm. But he and Barât – and the rest of us – would always have “Can’t Stand Me Now”, a laundry list of petty betrayals that gets you right in the chest. EP

Rex Features

The 40 greatest song lyrics Kate Bush – "Cloudbusting" "You're like my yo-yo/ That glowed in the dark/ What made it special/ Made it dangerous/ So I bury it/ And forget." Few artists use surrealism as successfully as Kate Bush – or draw inspiration from such unusual places. So you have “Cloudbusting”, about the relationship between psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich and his son, Peter, the latter of whom Bush inhabits with disarming tenderness. The way Peter’s father is compared to such a vivid childhood memory is a perfect, haunting testimony to the ways we are affected by loss as adults. RO

Rex

The 40 greatest song lyrics Nick Cave – "Into my Arms" “I don't believe in an interventionist God / But I know, darling, that you do / But if I did I would kneel down and ask Him / Not to intervene when it came to you." True, the lyrics spew and coo and, written down, resemble something Robbie Williams might croon on his way back from the tattoo parlour (“And I don't believe in the existence of angels /But looking at you I wonder if that's true”). Yet they are delivered with a straight-from-the-pulpit ferocity from Cave as he lays out his feelings for a significant other (opinions are divided whether it is directed to the mother of his eldest son Luke, Viviane Carneiro, or to PJ Harvey, with whom he was briefly involved). He’s gushing all right, but like lava from a volcano, about to burn all before it. EP

Getty

The 40 greatest song lyrics Sisters of Mercy – "This Corrosion" “On days like this/ In times like these/I feel an animal deep inside/ Heel to haunch on bended knees.” Andrew Eldritch is the great forgotten lyricist of his generation. Dominion/Mother Russia was a rumination on the apocalypse and also a critique of efforts to meaningfully engage with the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War. Ever better, and from the same Floodlands album was “This Corrosion” – a track more epic than watching all three Lord the Rings movies from the top of Mount Everest. Amid the choirs and the primordial guitars, what gives the nine-minute belter its real power are the lyrics – which may (or may not) allude to the not-at-all amicable departure from the Sisters of Wayne Hussey and Craig Adams. Either way, Eldritch paints forceful pictures in the listener’s head, especially during the stream of consciousness outro, unspooling like an excerpt from HP Lovecraft’s The Necronomicon or the Book of Revelations: The Musical. EP

Rex

The 40 greatest song lyrics Sultans of Ping FC – "Where's Me Jumper?" “It's alright to say things can only get better/ You haven't lost your brand new sweater/ Pure new wool, and perfect stitches/ Not the type of jumper that makes you itches.” Received as a novelty ditty on its debut in – pauses to feel old – January 1992, the Sultans’ lament for a missing item of woollen-wear has, with time, been revealed as something deeper. It’s obviously playful and parodying of angst-filled indie lyrics (of which there was no shortage in the shoe-gazy early Nineties). But there’s a howl of pain woven deep into the song’s fabric, so that the larking is underpinned with a lingering unease. EP

Flickr/Ian Oliver

The 40 greatest song lyrics The Smiths – "There is a Light that Never Goes Out" “Take me out tonight/Take me anywhere, I don't care/I don't care, I don't care.” As with Leonard Cohen, you could spend the rest of your days debating the greatest Morrissey lyrics. But surely there has never been a more perfect collection of couplets than that contained in their 1982 opus. It’s hysterically witty, with the narrator painting death by ten-ton truck as the last word in romantic demises. But the trademark Moz sardonic wit is elsewhere eclipsed by a blinding light of spiritual torment, resulting in a song that functions both as cosmic joke and howl into the abyss. EP

Rex

The 40 greatest song lyrics Bruce Springsteen – "I'm on Fire" “At night I wake up with the sheets soaking wet/ And a freight train running through the/ Middle of my head /Only you can cool my desire.” Written down, Springsteen lyrics can – stops to ensure reinforced steel helmet is strapped on – read like a fever-dream Bud Light commercial. It’s the delivery, husky, hokey, all-believing that brings them to life. And he has never written more perfectly couched verse than this tone-poem about forbidden desire from 1984’s Born in the USA. Springsteen was at that time engaged to actress/model Julianne Phillips though he had already experienced a connection to his future wife Patti Scialfa, recently joined the E-Street Band as a backing singer. Thus the portents of the song do not require deep scrutiny, as lust and yearning are blended into one of the most combustible cocktails in mainstream rock. EP

(Photo by Brian Ach/Getty Images for Bob Woodruff Foundation)

The 40 greatest song lyrics Tori Amos – "Father Lucifer" “He says he reckons I'm a watercolour stain/ He says I run and then I run from him and then I run/ He didn't see me watching from the aeroplane/ He wiped a tear and then he threw away our apple seed.” The daughter of a strict baptist preacher, Amos constantly wrote about her daddy issues. Father Lucifer was further inspired by visions she had received whilst taking peyote with a South American shaman. The result was a feverish delving into familial angst, framed by a prism of nightmarish hallucination. It’s about love, death, God and the dark things in our life we daren’t confront – the rush of words delivered with riveting understatement. EP

AFP/Getty

The 40 greatest song lyrics Public Enemy – "Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos" “I got a letter from the government/ The other day/I opened and read it/It said they were suckers/ They wanted me for their army or whatever/ Picture me given' a damn, I said never.” Decades before Black Lives Matter, Chuck D and Public Enemy were articulating the under siege reality of daily existence for millions of African-Americans. Black Steel, later covered by trip-hopper Tricky, is a pummelling refusal to be co-opted into American’s Land of the Free mythology – a message arguably as pertinent today as when it kicked down the doors 30 years ago. EP

Secret Garden Party

The 40 greatest song lyrics Kendrick Lamar –" Swimming Pool (Drank)" “First you get a swimming pool full of liquor, then you dive in it/ Pool full of liquor, then you dive in it/ I wave a few bottles, then I watch 'em all flock”. Lamar is widely acknowledged as one of contemporary hip-hop’s greatest lyricists. He was never more searing than on this early confessional – a rumination on his poverty-wracked childhood and the addictions that ripped like wildfire through his extended family in Compton and Chicago. There is also an early warning about the destructive temptations of fame as the young Kendrick is invited to join hip hop’s tradition of riotous excess and lose himself in an acid bath of liquor and oblivion. EP

Getty Images for NARAS

The 40 greatest song lyrics Prince – "Sign O' the Times" “A skinny man died of a big disease with a little name/ By chance his girlfriend came across a needle and soon she did the same.” Prince’s lyrics had always felt like an extension of his dreamily pervy persona and, even as the African-American community bore the brunt of Reagan-era reactionary politics, Prince was living in his own world. He crashed back to earth with his 1987 masterpiece – and its title track, a stunning meditation on gang violence, Aids, political instability and natural disaster. EP

Getty Images

The 40 greatest song lyrics Rolling Stones – "Gimme Shelter" "War, children, it's just a shot away/ It's just a shot away." Nobody captured the violent tumult of the end of the Sixties better than Mick, Keith and co. Their one masterpiece to rule them all was, of course, “Gimme Shelter”. Today, the credit for its uncanny power largely goes to Merry Clayton’s gale-force backing vocals. But the Satanic majesty also flows from the lyrics – which spoke to the pandemonium of the era and the sense that civilisation could come crashing in at any moment. EP

Redferns

The 40 greatest song lyrics David Bowie – "Station to Station" “Once there were mountains on mountains/ And once there were sun birds to soar with/ And once I could never be down/Got to keep searching and searching.” Which Bowie lyrics to single out? The gordian mystery of Bewlay Brothers? The meta horror movie of Ashes to Ashes? The uncanny last will and testament that was the entirety of Blackstar – a ticking clock of a record that shape-shifted into something else entirely when Bowie passed away three days after its release? You could stay up all night arguing so let’s just pick on one of the greats – the trans-Continental odyssey comprising the title track to Station to Station. Recorded, goes the myth, in the darkest days of Bowie’s LA drug phase, the track is a magisterial eulogy for the Europe he had abandoned and which he would soon return to for his Berlin period. All of that and Bowie makes the line “it’s not the side effects of the cocaine…” feel like a proclamation of ancient wisdom. EP

Express/Getty

The 40 greatest song lyrics Oasis – "Supersonic" “She done it with a doctor on a helicopter/ She's sniffin in her tissue/ Sellin' the Big Issue.” There is shameless revisionism and then there is claiming that Noel Gallagher is a great lyricist. And yet, it’s the sheer, triumphant dunder-headedness of Oasis’ biggest hits that makes them so enjoyable. Rhyming “Elsa” with “Alka Seltzer”, as Noel does on this Morning Glory smash, is a gesture of towering vapidity – but there’s a genius in its lack of sophistication. Blur waxing clever, winking at Martin Amis etc, could never hold a candle to Oasis being gleefully boneheaded. EP

Rex

The 40 greatest song lyrics Underworld – "Born Slippy" “You had chemicals boy/ I've grown so close to you/ Boy and you just groan boy.” The ironic “lager, lager, lager” chant somehow became one the most bittersweet moments in Nineties pop. Underworld never wanted to be stars and actively campaigned against the release of their contribution to the Trainspotting score as a single. Yet there is no denying the glorious ache of this bittersweet groover – or the punch of Karl Hyde’s sad raver stream-of-consciousness wordplay. It’s that rare dance track which reveals hidden depths when you sit down with the lyrics. EP

Getty

The 40 greatest song lyrics Fleetwood Mac – "Landslide" "And I saw my reflection in the snow-covered hills/ Till the landslide brought me down" Stevie Nicks was only 27 when she wrote one of the most poignant and astute meditations on how people change with time, and the fear of having to give up everything you’ve worked for. RO

Getty Images

The 40 greatest song lyrics Paul Simon – "Graceland" “She comes back to tell me she's gone/ As if I didn't know that/ As if I didn't know my own bed.” With contributions from Ladysmith Black Mambazo and the Boyoyo Boys, Simon’s 1986 masterpiece album is regarded nowadays as a landmark interweaving of world music and pop. But it was also a break-up record mourning the end of his marriage of 11 months to Carrie Fisher. The pain of the separation is laid out nakedly on the title track, where he unflinchingly chronicles the dissolution of the relationship. EP

Getty

The 40 greatest song lyrics Lou Reed – "Walk on the Wild Side" "Candy came from out on the island/ In the backroom she was everybody's darling/ But she never lost her head/ Even when she was giving head/ She says, hey baby, take a walk on the wild side." Reed’s most famous song paid tribute to all the colourful characters he knew in New York City. Released three years after the Stonewall Riots, “Walk on the Wild Side” embraced and celebrated the “other” in simple, affectionate terms. The Seventies represented a huge shift in visibility for LGBT+ people, and with this track, Reed asserted himself as a proud ally. RO

AFP/Getty Images

The 40 greatest song lyrics Sharon Van Etten – "Every Time the Sun Comes Up" “People say I'm a one-hit wonder/ But what happens when I have two?/ I washed your dishes, but I shit in your bathroom.” The breakdown of a 10 year relationship informed some of the hardest hitting songs on the New Jersey songwriter’s fourth album. Are We There. She takes no prisoner on the closing track – a tale of domesticity rent asunder that lands its punches precisely because of Van Etten’s eye for a mundane, even grubby, detail. EP

Ryan Pfluger

The 40 greatest song lyrics Patti Smith – “Gloria” “Jesus died for somebody's sins but not mine/ Meltin’ in a pot of thieves/ Wild card up my sleeve/ Thick heart of stone/ My sins my own/ They belong to me” The song that launched a thousand punk bands. It takes three minutes to get to Van Morrison’s chorus on Patti Smith’s overhaul of “Gloria”, where she lusts after a girl she spots through the window at a party. Before that, there is poetry. She snarls and shrieks as though her vocal chords might rip. The ostentatiousness of the lyrics owes as much to poets Arthur Rimbaud and Baudelaire as it does to Jim Morrison. RO

Samir Hussein/Redferns

The 40 greatest song lyrics The Eagles – "Hotel California" “There she stood in the doorway/ I heard the mission bell/ And I was thinking to myself/ This could be Heaven or this could be Hell.” A cry of existential despair from the great soft-rock goliath of the Seventies. By the tail-end of the decade the Eagles were thoroughly fed up of one another and jaundiced by fame. The titular – and fictional – Hotel California is a metaphor for life in a successful rock band: “You can check-out any time you like / But you can never leave.” The hallucinatory imagery was meanwhile inspired by a late night drive through LA, the streets empty, an eerie hush holding sway. EP

Rick Diamond/Getty Images

The 40 greatest song lyrics Thin Lizzy – "The Boys are Back in Town" “Guess who just got back today/ Them wild-eyed boys that had been away/ Haven't changed that much to say/But man, I still think them cats are crazy.” A strut of swaggering confidence captured in musical form – and a celebration of going back to your roots and reconnecting with the people who matter. Thin Lizzy’s biggest hit was in part inspired by Phil Lynott’s childhood memories of a Manchester criminal gang. The gang members were constantly in and out of prison and the song imagines one of their reunions – even name-checking their favourite hangout of Dino’s Bar and Grill where “the drink will flow and the blood will spill”. EP

REX

The 40 greatest song lyrics Nina Simone – "Four Women" "I’ll kill the first mother I see/ My life has been too rough/ I’m awfully bitter these days/ Because my parents were slaves." Included on her 1966 album Wild is the Wind, Simone depicts four characters – Aunt Sarah, Saffronia, Sweet Thing and Peaches – who represent different parts of the lasting legacy of slavery. Some critics accused her of racial stereotyping, but for Simone, it was these women’s freedom to define themselves that gave them their power. RO

Getty

The 40 greatest song lyrics St Vincent – "Digital Witness" “Digital witnesses/ what’s the point of even sleeping?/ If I can’t show it, if you can’t see me/ What’s the point of doing anything?” One of the best songs written about the illusory intimacy fostered the internet. St Vincent – aka Texas songwriter Annie Clark – was singing about how social media fed our narcissism and gave us a fake sense of our place in the world. EP

Anthony Harvey/Getty Images

The 40 greatest song lyrics Frank Ocean – "Pink + White" "Up for air from the swimming pool/ You kneel down to the dry land/ Kiss the Earth that birthed you Gave you tools just to stay alive/ And make it up when the sun is ruined." Co-written with Pharrell and Tyler, the Creator, “Pink + White” stands out even on an album like Frank Ocean’s Blonde. He sings – with a gently swaying, almost resigned delivery – surrealist lyrics that likens a past relationship to a brief high, from the perspective of the comedown that follows. RO

Getty Images

The 40 greatest song lyrics Rufus Wainwright – "Dinner at Eight" “If I want to see the tears in your eyes/ Then I know it had to be/ Long ago, actually in the drifting white snow/You loved me.” Piano-man Wainwright can be too ornate for his own good. But how he lands his blows here in this soul-baring recounting of a violent disagreement with his father. Loudon III, a cult folkie in his own right walked out on the family when Rufus was a child and the simmering resentments had lingered on. They boiled over at a joint Rolling Stone photoshoot during which Rufus had joked that his dad needed him to get into Rolling Stone and his father had not taken the insult lying down. The dispute is here restaged by Wainwright the younger as a raging row at the dinner table. EP

Getty

The 40 greatest song lyrics Bob Dylan – "It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)" "Pointed threats, they bluff with scorn/ Suicide remarks are torn/ From the fool's gold mouthpiece/ The hollow horn plays wasted words/ Proves to warn that he not busy being born/ Is busy dying." “It’s Alright Ma” is a cornerstone in Dylan’s career that marks his shift from scrutinising politics to sardonically exposing all the hypocrisy in Western culture. He references the Book of Ecclesiastes but also Elvis Presley, and offers up the grim perspective of a man whose views do not fit in with the world around him. RO

(Photo by Express Newspapers/Getty Images)

The 40 greatest song lyrics ABBA – "The Winner Takes it All" “I don't wanna talk/ About the things we've gone through/ Though it's hurting me/ Now it's history.” The first and last word in break-up ballads. The consensus is that it was written by Björn Ulvaeus about his divorce from band-mate Agnetha Fältskog, though he has always denied this, saying “is the experience of a divorce, but it's fiction”. Whether or not he protests too much the impact is searing as Fältskog wrenchingly chronicles a separation from the perspective of the other party. EP

AFP/Getty Images

The 40 greatest song lyrics Nas – "The World is Yours" "I'm the mild, money-getting style, rolling foul/ The versatile, honey-sticking wild golden child/ Dwelling in the Rotten Apple, you get tackled/ Or caught by the devil's lasso, s*** is a hassle" Nas addresses both himself and his future progeny on one of the best tracks from his faultless debut Illmatic. Inspired by the scene from Scarface in which Tony Montana sees a blimp with the message “The World is Yours” during a visit to the movie theatre, it feeds back to the rapper’s own belief that certain signs will appear to convince you that you’re on the right track. RO

The 40 greatest song lyrics The Stone Roses – "I Wanna Be Adored" “I don’t have to sell my soul/ He’s already in me/ I don’t need to sell my soul/ He’s already in me.” A statement of intent, a zen riddle, a perfect accompaniment to one of the greatest riffs in indie-dom - the opening track of the Stone Roses’s 1989 debut album was all of this and much more. The lyrics are supremely economical – just the chorus repeated over and over, really. But these are nonetheless amongst the most hypnotic lines in pop. Adding poignancy is the rumour that the Roses wrote it as an apology to early fans reportedly aghast that the group had signed a big fat record deal. EP

Getty Images

The 40 greatest song lyrics The Beatles – "When I'm Sixty Four" "When I get older losing my hair/ Many years from now/ Will you still be sending me a Valentine/ Birthday greetings bottle of wine?" There are hundreds of great songs about epic, romantic love, and there are hundreds of other Beatles songs that could have made this list. But this track from Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band – written by a 16-year-old Paul McCartney – is one of the greats for how it encapsulates a kind of love that is less appreciated in musical form. It’s less “I’d take a bullet for you” and more “put the kettle on, love”. It’s adorable, full of whimsy, and just the right amount of silly. RO

Getty

The 40 greatest song lyrics Beck – "Loser" “In the time of chimpanzees I was a monkey / Butane in my veins so I'm out to cut the junkie.” “Man I’m the worst rapper in the world – I’m a loser,” Beck is reported to have said upon listening back to an early demo of his break-out hit (before it had acquired its iconic chorus) . This gave him an idea for the hook and he never looked back. The stream of consciousness lyrics cast a spell even though they don’t make much sense – ironic as Beck was setting out the emulate the hyper-literate Chuck D. EP

And Vicious did initially confess to the crime, declaring “I did it … Because I’m a dirty dog”, before retracting his statement, saying he had been asleep when it happened. The quantity of barbiturates he is known to have consumed that night – 30 Tuinal tablets, a powerful sedative – would certainly support the argument he was “out cold” at the time.

Many have speculated the whole tragic episode was the result of a botched suicide pact, the couple romanticised as punk’s very own Romeo and Juliet.

Sex Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren , admittedly never an entirely trustworthy source, remained unwavering in his defence of Vicious, criticising the police investigation into the incident and telling The Daily Beast in 2009: “She was the first and only love of his life ... I am positive about Sid’s innocence.”

An alternative case has been made by Phil Strongman in Pretty Vacant: A History of UK Punk (2007), arguing that one Rockets Redglare – a bodyguard, drug dealer and hanger-on who died in 2001 – could be the true culprit, stabbing Spungen with a bowie knife after she confronted him about his stealing from Vicious.

Redglare, Strongman says, was heard boasting openly about committing the murder to fellow revellers at CBGB’s, New York’s punk mecca.

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Sign up Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Sign up And it’s true that cash was certainly lifted from Vicious’s room that night. He was in the money: he had recently capitalised on his notoriety by releasing a cover of “My Way”, vandalising Frank Sinatra’s signature song and bankrolling his appetite for narcotics with the proceeds.

Whatever the truth, Vicious and Spungen have become as inseparable in death as Cathy and Heathcliff – not least as a result of Alex Cox’s 1986 biopic Sid & Nancy, starring Gary Oldman and Chloe Webb. That film speculated that Vicious did stab her, albeit while keeping it ambiguous as to whether it was intentional or accidental.

Sid Vicious on Nancy's death Their outlaw image has been reproduced ever since, almost to the point of meaninglessness. Today, their importance as icons far outstrips Vicious’s minimal accomplishments as a musician. McLaren called Vicious “the ultimate DIY punk idol: someone easy to assemble and therefore become”.

John Lydon , the Pistols’ snarling frontman, expressed his regret at ever having drafted his childhood friend into the band, remarking in 2014: “He didn’t stand a chance. His mother was a heroin addict. I feel bad that I brought him into the band, he couldn’t cope at all. I feel a bit responsible for his death.”

It was Vicious’s mother, Anne Beverley, who had supplied the heroin that killed him and it was her who found his body the next morning, lying on the floor next to a needle and a charred spoon.

Described by Lydon as “an oddball hippie” in Rotten: No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs (1993), Beverley had separated from Vicious’s father and moved around a lot during his childhood, including a spell in Ibiza where she reportedly sold cannabis to make a living. She finally settled in Hackney.

A vain but unpredictable adolescent in thrall to Eddie Cochran and glam rock, Sid Vicious was given his name by Lydon in honour of the latter’s pet hamster; both were prone to bite.

In punk’s earliest days, Vicious was a regular at Oxford Street’s 100 Club, known for clearing the dance floor by swinging a bike chain, throwing drinks, and apparently inventing pogo dancing by leaping up and down on the spot to get a clearer look at the stage.

He was the original drummer for Siouxsie and the Banshees at their first gig at the venue and was one of the many members of the aborted Flowers of Romance, a band that might have amounted to a super-group had it ever got off the ground; its members included Viv Albertine and Palmolive of The Slits, Keith Levene who was later in Lydon’s Public Image Limited, and Marco Pirroni, guitarist to Adam Ant.

Joining the Pistols in 1977 gave Vicious an outlet for his anger. The band’s meteoric rise, and fall, from the Manchester Lesser Free Trade Hall to their final show at San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom, was as brilliant as it was brief.

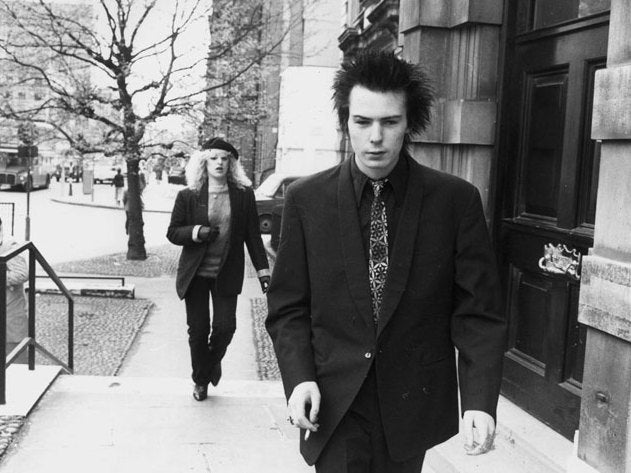

Sid Vicious and Nancy Spungen (Chalkie Davies) The Sex Pistols , a runaway train of engineered chaos and anti-establishment provocation steered by the extremely canny McLaren, allowed Vicious to indulge his every primal instinct for an audience of enraptured teens drawn to his sneering persona. The drug-taking wasn’t the half of it; his self-destructive, attention-seeking behaviour even stretched to self-harming with the serrated lid of a Heinz Baked Beans tin, while he and Spungen would burn each other’s arms with cigarettes.

Accounts of what Vicious was really like vary depending on who you ask. Stories of his physically abusing Spungen, vomiting on groupies, strangling cats, and brawling with rednecks on the Pistols’ disastrous US tour certainly abound. But others who knew him tell a different story. Steve Severin of the Banshees has commented that “he had a brilliant sense of humour, goofy, sweet, and very cute”.

Spungen’s middle-class mother, Deborah, recalls him as being endearingly shy, childlike and inarticulate when he visited her at home in Philadelphia. And he was certainly desperately in love with her daughter. In her own book about Sid and Nancy, And I Don’t Want to Live This Life (1983), its title one of Vicious’s own lines, Deborah records him telling her tearfully over the phone from prison: “I don’t know why I’m alive anymore, now that Nancy is gone.”

And what of Nancy? The 20-year-old is usually written off as a destructive junkie, a low-life chancer and a bad influence on everyone she met. Spungen was to the Pistols what Yoko Ono had been to The Beatles and Courtney Love would be to Nirvana, the argument goes. Worse, she was a contaminant, importing heroin chic from New York to London when she followed another punk band, Johnny Thunders and the Heartbreakers, across the Atlantic. But there is more than a hint of misogyny in such dismissals.

She is also now believed to have had an undiagnosed psychiatric condition. Her mother’s memoir describes Spungen’s disturbing behaviour as a child, from threatening her siblings during temper tantrums to attacking a babysitter with scissors.

Support free-thinking journalism and attend Independent events Ultimately, Sid and Nancy’s grotty demise stands as a cautionary tale, warning that the ruinous nihilism they came to represent amounted to little more than a dead-end. Their defiance led them only to a darkened room at the Chelsea Hotel, and a spiral of mutually-assured destruction.

The post-punk and new wave movements that Lydon and his peers went on to embrace were far more optimistic, joyous and experimental, entertaining grander visions of a better world – something that Vicious and Spungen seemingly couldn’t imagine, and tragically never saw. The “no future” refrain from “God Save the Queen” proved to be a self-fulfilling prophecy for the young lovers.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies