Anthony Quinn, Freya: 'Once you let her in she’ll stay for ever', book review

Quinn is the literary equivalent of Houdini, a novelist who has a particular talent for absenting himself and letting his characters come to life

At the beginning of Anthony Quinn’s new novel his spirited heroine tries to explain the problems with an unpublished manuscript written by her friend, Nancy.

“I think it comes down to trusting one’s characters; once you’ve got them on the stage, so to speak, you should let them tell and act for themselves.

The writer should perform a kind of disappearing act.”

By his own terms, Quinn is the literary equivalent of Houdini, a novelist who has a particular talent for absenting himself and letting his characters come to life. The story centres on two friends, Freya Wyley (whom we first met as a rebellious 12-year-old in Quinn’s fourth novel, the brilliant Curtain Call) and Nancy Holdaway.

The action moves quickly from VE Day 1945, through Oxford (where both women go to university), post-war London (where Freya establishes herself as a journalist, and aspiring novelist Nancy works for a publisher) and then on into the early 1960s.

Quinn explores the big issues of the century – feminism, homosexuality, immigration, the individual versus society – but does so with a deceptively light touch. He draws us into the consciousness of his protagonists in an utterly compelling way.

While Curtain Call invoked the Golden Age mysteries of Agatha Christie – the story was structured around the question of who was the tie-pin killer – Freya is much more a study in character. Although it’s a joy to meet old friends (such as theatre critic Jimmy Erskine and Freya’s father, the painter Stephen Wyley) whom we first encountered in Quinn’s previous novel, this book can be read as a standalone.

He makes the reader fall in love with Freya, whom Nancy takes as the inspiration for the character Stella in her own published novel “The Hours and Times” – “none would ever forget her, so thrumming with life was the portrayal”.

And so it is with Freya, who gets sent down from Oxford for missing her exams on the off chance of travelling to Nuremberg to write a profile of a distinguished female war correspondent, Jessica Vaux.

We follow Freya’s career from university – where she is seen as nothing more than “a skirt with a library book” – to reporter and feature writer on national newspapers, where she specialises in penning witty portraits of the demi-monde of London.

The 15 best opening lines in literature

Show all 15We smile and laugh along with Freya as she notices the absurdities and pretensions of those around her, such as an announcement of a sonnet-writing competition at Oxford that reads “Enjambement will be permitted between the eighth and ninth lines”.

There is a certain quality of deliciousness that is missing from a great deal of English prose. But Quinn has oodles of it. One of the characters quotes Flaubert’s famous aphorism: “Prose is like hair, it shines with the combing.” Quinn is a master with the stylistic hairbrush, delicately honing his sentences until they have just the right sheen.

A pair of ice cream cones bought by Nancy for the purpose of lifting Freya’s spirits is described as “torches to light their way”. The sight of something in the sky – which turns out to be a hawk – is “a faint dark flake, like a screw of charred paper rising from a bonfire.”

Hermann Göring – the leading Nazi tried and found guilty at Nuremberg of war crimes, as observed by the correspondent Jessica Vaux – has the look of “the madam of a brothel … his professional mask enacting a cold struggle between geniality and calculation”.

The friendship between Freya and Nancy is explored in all its many nuances, from the initial heady thrill of first meeting, through sexual, emotional and professional rivalries, to the sting of betrayal, and the soft tenderness of reconciliation and forgiveness.

The two women also share a bond of childlessness – while Nancy and her husband cannot have any, Freya finds herself pregnant by an estranged Italian lover and then loses the baby (a scene that Quinn writes with terrific empathy).

The cast of accompanying characters – which includes an ambitious writer turned Labour politician, a playwright with sado-masochistic tendencies, a vulnerable teenage model (all big eyes and bird-like frame), and a homosexual photographer who seems to have been inspired by John Deakin – is equally vivid.

“It’s funny how some characters, mere figments on the page, never really die in our heads, or hearts,” observes one of the protagonists at the end of the novel. “We think about them even after we’ve clapped shut the book.”

Quinn’s characters, particularly the vivid, maddening, wilful, foul-mouthed and frequently funny Freya, will continue to live on long after reaching the final line of this wonderful novel.

‘Alexander McQueen: Blood Beneath the Skin’ (Simon & Schuster, £9.99), a biography of the fashion designer by Andrew Wilson, is published in paperback on 10 Mar

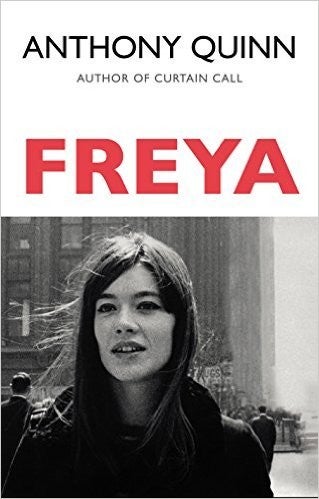

Freya, by Anthony Quinn. Jonathan Cape £14.99

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies