Francis Wyndham: Bruce, Jean, Vidia and me

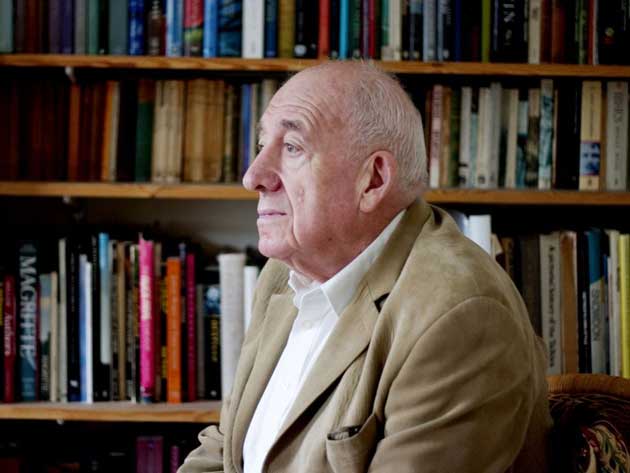

Journalist and critic Francis Wyndham has been a mentor to Jean Rhys, Bruce Chatwin, Alan Hollinghurst and VS Naipaul. As his own short stories are republished, he talks to the novelist Edward St Aubyn and Suzi Feay about his legendary literary life

The scene: a fashionable restaurant in London's Notting Hill.

Edward St Aubyn: Francis, I've just reread your fiction and the main thing that struck me is that it's wildly enjoyable. Mrs Henderson and Other Stories: the brilliance of that, the glittering quality of that is something extraordinary. How much do you think about the reader's pleasure when you're writing?

Francis Wyndham: I think it's paramount. That's the point of writing and the point of reading, what else can there be? But of course different people enjoy different things.

EA: I don't think anyone could fail to enjoy Mrs Henderson. And indeed The Other Garden, which is very moving and very upsetting as well. It has less glitter and more elegy than Mrs Henderson, it has a different mood, but it's also deeply enjoyable.

FW: I was rather pleased with myself that Sybil, the villain in The Other Garden, is a comic character. I thought that was rather Dickensian, like in Martin Chuzzlewit. Mr Pecksniff is hilariously funny and really seriously nasty. Recently I reread Mother's Milk and you've done that too with Seamus, who's the villain in that, and at the same time hysterically funny. Sybil sums up a lot of things I didn't like about that period during the war.

EA: She has an incredibly destructive presence yet is wildly comic at the same time. I'm very interested in the margins between comedy and tragedy, broadly speaking.

FW: Me too, and your work combines them. I'm interested in clarity and not in ambiguity. You try for the right word, the right sentence, the right paragraph. But you hope that by doing that something, a sort of alchemy will happen and something else will come off the pages, which will be different for every reader.

EA: I think that sense is so strong in you because of your own relationship with reading, being so receptive and so intense.

FW: I've always absolutely loved reading. I'm very pleased that I did sort of become a writer as well. I made my living as a journalist. That was great fun. But the stories were written out of the blue. The early ones were unpublished for about 30 years. They were rejected when I wrote them originally.

EA: The impact that had on you is very sad. Do you think that stopped you writing more?

FW. It didn't help, you know? It was during the war when there wasn't any paper anyway. It was difficult for anybody to get published then. So I don't think I was ill done by. But the mere fact that they were not about fighting the war eventually became interesting. That's what I mean about the reader being so important. Readers were rather interested in what it was like just hanging around on the home front.

EA: But when they were published, you then wrote the two other books soon after. So encouragement and discouragement do play a part. That's what strikes me, how fragile confidence is; that someone can be an excellent writer, as you are, and be defeated by rejections to a significant degree.

FW: The fact that they were welcomed and people liked them gave me enormous confidence. Exactly.

EA: Those stories in Out of the War; you wrote them between 17 and 21, is that right?

FW: Sort of, yes.

EA: A lot of the stories are centred in the lives of young women living with their mothers. You, at that time, were someone who was between Eton and Christ Church, with a completely different life from the lives you were describing.

FW: I didn't want to write about myself, I wanted to write about what was going on around me. Some are in the first person, some aren't stories at all, just sort of impressionistic things. I was just feeling my way. Some people have thought about Mrs Henderson that there is not enough about the narrator.

EA: I disagree. I think the narrator is a witness and we know what sort of witness he is from the things that he chooses to notice. He doesn't thrust himself forward, but all the better for that.

FW: The novel is only just a novel, it's sort of a novella. Everything I do is always going to be a short story, because that's all that's been in my power. Of course, I longed to say "I'm a novelist!" I only could – just – years later say that after The Other Garden.

EA: But The Other Garden is a novel – you say "only just", and it's like a short story, but you could argue the opposite: that the two books of short stories are like novels in the sense that they have an unusually high unity; that Mrs Henderson is, in fact, aspects of the same narrator's life.

FW: It's supposed to be read in that order.

EA: But you've suppressed some of the waffle and the explanation which links up the aspects of the lives you're writing about, and just written the things you are interested in, which makes it more intense.

FW: It never entered my head that the short story was somehow inferior to a novel. I knew that I felt that that was all I was capable of and I still think it's almost artificial to think they're different.

EA: A story like "Ursula" in Mrs Henderson looks at a whole life with the discipline of remaining with the narrator's point of view. I found that story very touching. There's something about Ursula that is true of you as well: her unsnobbishness, her egalitarian impulses, her idealism. Do you recognise that quality in yourself? The quality in her that you describe so well in this story?

FW: I'm very very sympathetic to it. The person that she was based on in real life was my half-sister and the fictional character was much purer than me. I think I understand sometimes why people are snobbish!

SF: How long were you at The Sunday Times?

FW: From 1964 to 1980. A very long time. I loved doing interviews but I didn't have one of those things [points to tape recorder], I did it with notes and remembering. I used one for an early thing I did with the Pretty Things, who came out after the Rolling Stones. There was so much! I couldn't boil it down. So from then on I'd just make a note of a key word. I didn't have shorthand. I never had any complaints; nobody ever wrote in and said: "I never said any of that, he's gone mad."

SF: That's quite a novelistic way of doing it.

EA: It's a novelistic talent, exactly, to rely on yourself to be able to replicate how someone speaks, the atmosphere of their presence, just to want a few key words.

FW: My aim was to make interviews like little stories. The fun of it all was that they were all with a photographer and the point was the pictures. So you didn't have to do that very difficult thing which was to describe what somebody looked like. That was all done for you. All you had to do was to get how they talked. I never interviewed writers, because I thought it was totally pointless. Why interview a writer? He's said it all in his books, if he's any good. Also perhaps I was shy of doing so.

EA [laughs]: Do you still feel it's pointless to interview writers, Francis?

FW: Just for me, yes. I don't think it's pointless for anybody else. I interviewed actors and actresses. It was absolutely bloody money for jam! It was when I was on Queen magazine with dear Mark [Boxer]. Somebody wangled an interview with Elizabeth Taylor. Not the author Elizabeth Taylor, who's one of my favourite writers, but the actress at the height of her fame, with Burton. I went off and did it. I woke up famous! The telephone kept ringing – it was the interview with Elizabeth Taylor that everybody read! It's hard to believe now. She didn't say anything and I kind of wrote about what I saw. I suddenly thought, I'm going to do interviews from now on.

SF: That's a great old tradition, maybe started by you, of the terrible interview that you turn around just by describing the interview itself. Was writing journalism a substitute for doing your own writing?

FW: Well, it was quite different. I was rather dependent on speed, and my journalism was completely fuelled by that, but the stories and novels weren't at all. I'd get up early in the morning and take a pill, and rrrrrrrrrr! Then go into the office with the piece. But I think – yes, because after all, I was writing, wasn't I? So it was.

SF: There's still a pleasure in putting good sentences together, isn't there?

FW: Exactly. And it developed my ear which is so important.

SF: Is Francis one of the people to whom you submit work in progress?

EA: Yes. Since we met, I've written On the Edge, A Clue to the Exit and Mother's Milk and he's seen all of those more or less chapter by chapter. And it's been incredibly encouraging and helpful to me.

FW: You can imagine, it's so wildly enjoyable to be actually given, fresh from...

SF: The rest of us have to wait years for our fix.

EA: I show my work to hardly anyone else. Francis has a particular kind of sympathy and intelligence which is incredibly nourishing to a writer who's working. And it's a feature of your life, isn't it, that you've been this guide and help and midwife to lots of writers: Bruce Chatwin, Naipaul, Jean Rhys, Alan Hollinghurst.

SF:What was it like working with Jean Rhys?

FW: She used to write to me and send me bits [of Wide Sargasso Sea] and that was an exciting feeling of being in on something I knew was good. I just gave encouragement.

SF: Are you very tactful? Is that your secret? Because some of these people are known for being touchy.

FW: I suppose I must have been. Well, it was quite easy to be tactful with the people we've mentioned, because they never fell below this very high standard. I think I err on the side of being tactless.

SF: The modern writer now has to get out and sell their wares and appear on stage...

FW: It's such a revolution. When I was growing up, you were very excited if your aunt had once met somebody who knew Daphne du Maurier.

SF: Are you going to launch yourself into a whirl of publicity now?

FW: Well, that's what we're doing here.

SF: It gets a lot worse than this!

EA: Oh yes. We're starting you off gently.

'The Other Garden and Collected Stories' by Francis Wyndham is published by Picador (£7.99) on 5 September

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies